The Napoleonic epic along the Paris metro

Among the intramural Paris metro stations, some are famous all over the world and reflect the great history of France. We thus read in filigree on the maps of Paris, the great moments of the Napoleonic epic.

The pride of the Grande Armée

Swarmed on almost all the lines of the Parisian metro, the great military names who forged the reputation of the Grande Armée reveal the importance of the Napoleonic Empire in the history of France. On line 6, the Cambronne station pays homage to the man who is still said to be the author of the famous “word”. Pierre Cambronne (1770 – 1842) , brilliant brigadier general then Major of the Imperial Guard in 1814, was one of Napoleon’s most loyal. At his side on the Island of Elba, he impressed the English at Waterloo (June 1815) with a determined but desperate resistance, responding forcefully to their summons to surrender with the famous word that made him famous: a “Shit ! Exasperated, the conciseness of which was unanimously appreciated in both camps. Dying on the battlefield, he was taken prisoner by the British and then freed. He died 27 years later in Nantes. Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885), whose aversion to the Second Empire was no secret, remembered the famous word and used it skillfully, believing that “Cambronne in Waterloo buried the First Empire in a word where the second was born. A remark which, no doubt, does not strengthen the already loose ties between Napoleon III and the writer.

A few stations from Cambronne, General Jean-Baptiste Kléber (1753 – 1800) also gave his name to a stop on line 6. Although he distinguished himself just as much during the wars of the French Revolution, his independence of mind did not allow him to access a command-in-chief. In 1797, Bonaparte took him with him to Egypt but left without his general to whom he gave before his departure the supreme command of the army of Egypt. Left in a delicate situation against the English, Kléber had to sign the D’El Arich agreement in January 1800. The latter scorned by Admiral Keith, the general resumed hostilities and brilliantly won the Battle of Heliopolis in March before being assassinated in Cairo in 1800. His ashes now rest on Place Kléber, in Strasbourg.

This walk in the Parisian metro is surprisingly to raise the English cowardice who financed the battle of Austerlitz or Battle of the Three Emperors without participating. Because the Gare d’Austerlitz station, line 10, bears the memory of this dazzling Napoleonic victory, the name of which was delicately removed from the Eurostar route when our teasing British neighbors did not spare us, a few years ago, a welcome to Waterloo. On December 2, 1805, Emperors Francis II and Alexander I faced the French Emperor strategist in southern Moravia. Napoleon’s tactical genius was deployed there from the country lanes to the battlefield, making a lasting mark on history: this warlike masterpiece is still taught in military schools today. On the same line, we find the memory of Molitor (1770 – 1849), Gabriel of his first name, who participated in many Napoleonic campaigns after having cut his teeth during the Revolution then remained faithful to the Emperor whom he joined during the Hundred Days. In 1809, he had distinguished himself at the battle of Wagram (which a station on line 3 is remembered for) just like Christophe de Michel du Roc dit Duroc (1772 – 1813) whose name also marks a stop on line 10 .

This grand marshal of the palace of Napoleon I inscribed his name in the Italian campaign but his diplomatic qualities earned him much more than military honors by obtaining the full confidence of Bonaparte. Courageous, intelligent and loyal, Duroc was personally responsible for the safety of the Emperor without renouncing important missions that Napoleon I wanted to see handled only by himself. On his death, extraordinary honors were paid to him and in 1815, the deposed Emperor chose nothing other than the name of Duroc to go to Rochefort from Malmaison. Today, the ashes of this brilliant man, whose name is engraved on the Arc de Triomphe, rest alongside Bonaparte at the Invalides.

On line 9, the Jena stop takes us to Germany, a memory of the battle of October 14, 1806 between the French and the Prussians. However, the German campaign had started well before and on October 7, 1805 in Donauwörth, almost a year to the day before Jena, Rémy Isidore Joseph Exelmans (1775 – 1852), known as “The lion of Rocquencourt”, saw himself honored with to carry to the Emperor the flags taken from the enemy. The reception he received marked him for a long time because Bonaparte was laudatory: “I know that we are not braver than you: I am making you an officer of the Legion of Honor. Make no mistake, the familiarity here was worth much more than the compliment. Napoleon I, after that, always spoke to him. Today a station bears the name of the man who won, just after the Emperor’s abdication, the last French victory in the Napoleonic wars. Had he, our Exelmans, obtained these same honors if he had not befriended Joachim Murat in his youth?

The same Murat who in the eyes of the Emperor was to the cavalry what Drouot was to the artillery. Antoine Drouot (1774 – 1847), whose name marked history as much as the art market, is today in the company of Richelieu: line 9, the Richelieu-Drouot station does not bother with characters. Does the ambitious Duke of Richelieu, skilful strategist, devious and intransigent get along with this Napoleonic general? If we believe the description given by Napoleon, surely the cohabitation is not easy …

“Drouot is one of the most virtuous and modest men there was in France, although he was endowed with rare talents. Drouot was a man […] who lived as satisfied, for what concerned him personally, on 40 sous a day as if he enjoyed the income of a sovereign. Charitable and religious, his morality, his probity and his simplicity would have been honored in the century of the most rigid republicanism. “

Ironically, we doubt we can attribute to the famous cardinal the qualities of the humble general while those which ordinarily characterize a general the cardinal possessed all of them.

On line 4, the Mouton-Duvernet and Morlan stations pay tribute to two soldiers fully engaged in the Napoleonic campaigns. Régis Barthélemy Mouton-Duvernet (1770 – 1816) distinguished himself in Arcole during the Italian campaign while François-Louis de Morlan dit Morland (1771 – 1805) died of his fatal wounds at the Battle of Austerlitz. His name appears today on the Arc de Triomphe.

Some Paris metro stations do not honor the memory of great people but those of memorable places. This is the case with the Louvre-Rivoli station, line 1, which serves the palace on the rue de Rivoli, named in honor of Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory over Austria on January 14, 1797. Likewise, the Campo-Formio station on line 5 celebrates the treaty signed on October 18, 1797 in the eponymous city of Veneto. This treaty closed the Franco-Austrian war for the first time and allowed France to obtain from Austria Belgium, part of the left bank of the Rhine, the Ionian Islands and the recognition of the Cisalpine Republic.

Line 7 and 14, the Pyramides station returns to the mythical places of the Egyptian countryside. With this innate sense of propaganda which always characterized him, Napoleon named the battle of July 21, 1798, which pitted him against the Mamluk forces with the name of “Battle of the Pyramids”. A very romantic name since the battlefield had in common with the venerable thousand-year-old monuments only to be extremely dusty.

The Simplon line 4 station takes us far from the hustle and bustle of Paris to remind us of the calm and invigorating air of the Swiss Alps, where Napoleon had a road built in the Simplon pass first, then a hospice whose first stone was laid in 1813.

Names of glorious soldiers still mark the stations Pelleport (line 3 bis), Pernety (line 13) or Lecourbe (line 6). General of the Empire Pierre de Pelleport (1773 – 1855) was of the first promotion of the Legion of Honor and participated in the Grand Army in the campaign of Austria, Germany and Poland, respectively in 1805, 1806 and 1807.

Joseph Marie de Pernety (1766 – 1856) was admired for his bravery during the Italian campaign, was part of all the great Napoleonic battles and Marshal of the Empire Massena did not fail to publicly compliment him during the Battle of Wagram.

Claude Lecourbe (1759 – 1815) also distinguished himself with talent, but not enough to forget his friendship with Jean Victor Marie Moreau (1763 – 1813), accused of conspiring with his wife against the rise to power of Bonaparte. Lecourbe, who had the courage (or the stupidity) to take a stand for his friend, was exiled to the Jura. When it was Napoleon’s turn to taste the bitterness of exile , he remembered Lecourbe “Very brave, he would have been an excellent Marshal of France; he had received from nature all the qualities necessary to be an excellent general. “

Let us not forget Armand Augustin Louis, fifth Marquis de Caulaincourt (1773 – 1827) who baptized, line 12, half of the name of a station, sharing the other half with the famous French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744 – 1829 ). If the two men have one day met, perhaps crossed paths, they were probably far from imagining that barely a century later they would dabble in the delicious promiscuity of the Parisian subways. Caulaincourt nevertheless had the opportunity throughout his life to taste the great outdoors since he was Russian Ambassador at a time when travel was difficult. When he returned from the Russian campaign, he was also the confidant of Bonaparte’s sleigh, an adventure of 14 days and 14 nights from which his famous story was born. In sleigh with the Emperor . His skill in the art of diplomacy allowed him to gain the confidence of the Emperor Napoleon I at the same time as that of Tsar Alexander I. Did this fine mind, “a man of heart and righteousness” according to Bonaparte himself, have any humor? No doubt not as much as Victor Faÿ de Latour-Maubourg (1768 – 1850) whose name adorns a station on line 8. Musketeer at 14, commander of the first cavalry corps at 45, he had his thigh torn off by a cannonball during the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813. His servant, more sensitive to physical losses than his master probably was, cried hot tears over his missing leg when Latour-Maubourg, who doubtless knew the virtues of positivism, addressed a remark that has remained famous to his valet:

Console yourself my friend, the harm is not so great for you… After all you will only have one boot to shine!

Scientists in the service of the Emperor

We know that Bonaparte is suspicious of doctors, even going so far as to doubt – a little by provocation – of the usefulness of medicine. On line 6 of the Paris metro, however, a station bears the name of the man who succeeded in convincing the First Consul and then the Emperor of the usefulness of this discipline. The Corvisart station thus pays homage to Jean-Nicolas Corvisart (1755 – 1821), a brilliant doctor with a thoughtful character who met Napoleon in July 1801 before quickly becoming his personal doctor. Once the Empire was established, the doctor was not only responsible for ensuring the health of the imperial family but also other missions relating to the management of epidemics and contagious diseases. The man, moreover, had little taste for the gold of the court and wanted his autonomy, which is why he refused accommodation in the Tuileries. His efficiency, his objectivity and his will to take care of the best surpassed his respect for etiquette, he who never hesitated to firmly rebut the Emperor who did not respect his prescriptions seriously enough. Conversely, Josephine’s bulimia on pills prompted her to regularly administer placebo in order to calm her anxieties without endangering her health. Faithful to the Emperor as a family doctor to his long-standing patients, Corvisart accompanied Bonaparte on several campaigns and again became his personal doctor during the Hundred Days, but his age forced him to stop practicing after Waterloo. Despite everything, he was one of the last to greet the Emperor before his departure for Rochefort. The man had succeeded where his discipline had failed, to say even Napoleon who declared: “I do not believe in medicine, but I believe in Corvisart. “

Gaspard Monge (1746 – 1818) meets on line 7. This renowned scientist marked the history of mathematics interested in geometry, infinitesimal analysis and analytical geometry. Also a professor of physics and topography, Monge was one of those scholars who produced an abundant, important and completely original work. His work on fortifications has since been known as descriptive geometry. Appointed Minister of the Navy during the Revolution, his knowledge and science concerning the weapons of war were immense. After the throes of the Revolution, he became a professor at the École normale supérieure and soon one of the founders of the École Polytechnique. In May 1796, he was appointed member of the commission charged with going to Italy to recover “the monuments of art and science which the peace treaties grant to the victorious French armies”. On this occasion he made the acquaintance of Bonaparte, then general. The two men liked and sympathized until they became close friends. Monge was also invited to the coronation of Napoleon I at Notre-Dame and exile in Saint Helena did not prevent Bonaparte from remembering in a laudatory manner his friend who was no less admired by Josephine. This man of science with considerable work was first buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery before his ashes were transported to the Pantheon.

Finally, line 5, let’s stop at the Breguet-Sabin station, not to pay tribute to the punctuality of the Parisian subways, but to the one who allowed it to be noticed: the watchmaker and physicist Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747 – 1823). Famous inventor of self-winding watches, we owe him the development of perpetual watches that took advantage of the movements of walking to wind themselves without any manipulation. Napoleon Bonaparte was one of his most loyal clients. Should we be surprised, he who could not bear to waste his time, it is quite natural that he appreciated the instruments capable of measuring it. In 1798, before the general’s departure for the Egyptian campaign, he purchased a repeater watch, a travel clock and a perpetual watch. Renowned for their reliability, solidity and refinement, Abraham-Louis Breguet watches had enough to seduce the young general, then in full political and social ascension. Once First Consul and then Emperor, Napoleon brought to the watchmaker an upscale and wealthy clientele who made his fortune. In particular, in 1810 Breguet manufactured the first wristwatch which was sold in 1812 to Caroline Murat, sister of the Emperor and Queen Consort of Naples.

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

With just over 300 stations, the metro serves Paris and its metropolitan area throughout the history of France. From Antiquity to the present day, the names of the stations bear witness to exchanges, conflicts, discoveries, culture and of course the great figures who marked the personality of the nation. If the location of the stations often corresponded to the streets which they served on the surface, the fact remains that the Napoleonic history, from the campaigns of Italy to the Empire, considerably imprinted its great names in the geography of the capital city. Note the absence of a Napoleon Bonaparte station, as are many French heads of state. King Philippe Auguste, Clémenceau or Mitterrand (in connection with the eponymous library) received this honor but the Parisian metro seems to have the preference for characters who have accompanied History, a way of keeping the memory alive and daily, while traveling through Paris. and its surroundings.

Napoleon and Josephine : an Ordinary Couple

The mythical couple formed by Napoleon and Joséphine still arouses curiosity today for these two characters seem absolutely opposite. This couple, which initially mixed fire and ice, was inconceivable except to be strangely ordinary ... in our contemporary eyes. Story of a modern couple.

A couple in contradiction in every way

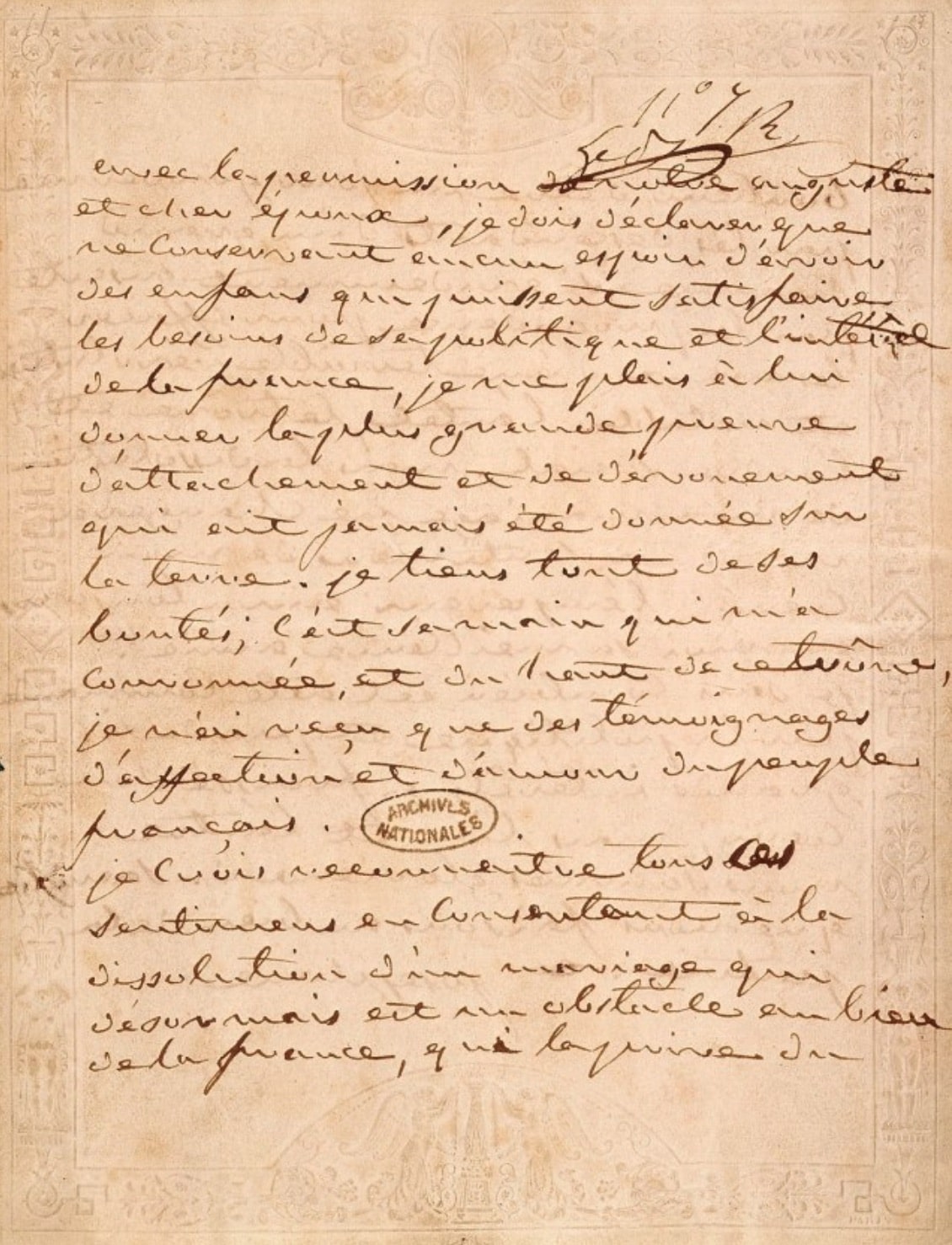

Joséphine de Beauharnais (1763 – 1814) met Napoleon for the first time (1769 – 1821) in 1795. She then reigned on the Directory alongside other young and elegant women – such as the spicy Madame Tallien – from whom she distinguished herself in being by far their eldest. Joséphine was 32 years old, widow and mother of two children. Her nobility was insignificant at best, while her debts enjoyed far more prestige than her name. With Napoleon, she pretended to be rich and he succumbed for a time to the charms of this deliquescent aristocracy; not enough, however, not to have the real state of her sweetheart’s finances checked. But whatever, this young man to whom Paul Barras (1755 – 1829) promised a great future, had to recognize that this marriage would be financially more favorable to him than to her: on March 8th, 1796, the marriage contract established indeed that Joséphine brought to the household her annual rent of 25,000 francs while Napoléon Bonaparte constituted for the moment a meager pension of 1,500 francs in case of widowhood… Napoleon was madly in love with her Josephine, and he could no longer bear the idea of marrying another woman than her. This state of mind was unfortunately not shared by this elegant woman. Her heart will not turned upside down for this man who was neither of her kind nor her spirit. What decided her was precisely what separated them from the start: for her, wedding was – as under the Ancien Regime – a matter of convenience and interests mixed, but in no case a matter of feelings! Napoleon, meanwhile, did not care about this separation of appearances and aspired to a marriage based on shared love, a very modern idea in this high society where the codes of a barely sleepy aristocracy still prevailed. When Josephine finally consented to this union, it was above all in order to preserve her worldly existence and the safety of her children. This glorious general brought her countenance and security at a time when Terror still haunted everyone. She thought by this marriage to preserve frivolities and worldliness, temporary gallantries and to ensure the security of the home. He imagined himself a fulfilled and loved husband of a wife who would take care of maintaining a respectable and happy home. Two worlds clashed without one figuring it out in the other.

Their respective correspondence is eloquent in this case. When Napoleon was moved “I wake up full of you”, Josephine complained to one of her friends “I find myself in a state of lukewarmness that I dislike and that the devotees find more vexing than anything”. Surely, Joséphine’s experience in the field of gallantry did not reveal anything of this lukewarmness to her husband. However, once he left for Italy, Madame Bonaparte’s undisguised indifference to the pleas of the general marked Parisian mind. Letters from Italy never dried up and arrived almost every day while responses were scarce and capricious. Tearful, lonely, barely consoled by his victories, how could one not feel all the general’s pain and despair when, impatient to get back (finally!) to her Josephine in Milan, he found the palace empty, the Beauty having eclipsed for enjoy the pleasures of Genoese society. In a heartbreaking letter, we read the general’s resignation:

I arrive in Milan, I rush to your apartment, I left everything to see you, to hug you; … you weren’t there: you run cities with parties; you move away from me when I arrive, you no longer care about your dear Napoleon. A whim made you love him, inconstancy makes you indifferent. Accustomed to dangers, I know the remedy for the troubles and evils of life. The unhappiness I experience is incalculable; I had the right not to count on it. I will be here until 9th. Do not bother ; run pleasures; happiness is for you. The whole world is too happy if you like it, and your husband alone is very, very unhappy.

The image of the uncompromising conqueror and strategist that Europe then discovered is far away here … The gap widened between the two spouses despite the perseverance of a Napoleon who suffered to admit that he was not loved by his wife. Returning from the Egyptian campaign, the threat of divorce hung over the young couple and Josephine measured with horror the damage she had committed. If the situation had nothing in common in this young XIXth century, what is original in our contemporary eyes?

The Bourgeois Understanding

By an ironic reversal of the situation of which life has the secret, it is Joséphine who will henceforth fear that Bonaparte will leave her. The latter having lost all illusions concerning his wife’s feelings towards him, gradually detached himself from her without ever taking away from him the affection that he had for her. If he could not demand mutual love, he nevertheless intended to maintain the tranquility and respectability of his house. These could not be more bourgeois demands for a man soon raised to imperial dignity. The entourage of the couple testified with astonishment to this family life far removed from the royal customs of his predecessors and to which we have always been used: “The Emperor was indeed one of the best husbands I have ever known” testifies Mademoiselle Avrillion (1774 – 1853), first maid of the empress. She continues “when the empress was inconvenienced, he spent with her as long as it was possible for him to steal from imperial matters […] He had a tender friendship for her”. The testimony of Louis Constant (1778 – 1845), the Emperor’s first valet, was no less unexpected “How touching was the agreement of this imperial household! Full of attention, respect, abandonment for Josephine, the Emperor liked to kiss her on the neck, in the face, patting her and calling her “my big beast”. And the “big beast” empress loved to read to her imperial husband in the evening! If the question of the heir was thorny, that of Joséphine’s children wasn’t and, as in a reconstituted family today, Napoleon I tenderly pampered his wife’s children. Hortense and Eugène were constantly at the center of his preoccupations and Bonaparte did not deny this nickname of “Bibiche” uncle which the son of Hortense gave him. Could these children have known a better stepfather? As in all modern households, arguments were inevitable, however. And if Napoleon Bonaparte imposed his will on Europe, he could hardly do so in his own home! Josephine was spending countless, and when her husband finally paid off her debts she had had plenty of time to create new ones. He, attached to order and regularity, succeeding by his genius in winning great battles across the continent, systematically failed to force Josephine to respect her budgets.

Were the domestic concerns of the imperial couple so different from the bourgeois concerns of the same era? If not the size of the house and the expenses, are they even different from ours? To be convinced, let’s add that pets did not escape this bourgeois life. Because the question arose: who will take the dog out? Not for his daily walk as you might think, but from Joséphine’s bed. Designating a frizzling hound (a poodle named Fortuné), Napoleon said to his friend Antoine-Vincent Arnault (1766 – 1834) “You see that gentleman here, he is my rival. He was in possession of Madame’s bed when I married her. I wanted to get it out: useless pretension, I was told that I had to make up my mind to sleep elsewhere or agree to share. » Napoleon knowing the dog unbeatable (an unpleasant irony for the one who won most of his battles) but not eternal, he took his pain in patience and the minute following the death of Fortuné, he strongly defended that a successor be designated. Wasting of time because Joséphine quickly went beyond her husband’s ban and acquired a pug. Furious, the Emperor then urged his cook to acquire a terrifying (and surely hungry) great mastiff in the hope that the latter would make his meal from the unwanted doggie.

Infidelities and Divorce

Joséphine at the start of their relationship and during their first years of wedding deceived Napoleon with a casualness that marked the minds, to the point that Barras advised her to be careful in her relations with Charles Hippolyte (1773 – 1837). Then she was the one who feared her husband’s infidelities. A foreboding rightly worried her during Bonaparte’s stay in Poland in 1807. The Emperor and Mrs. Walewska (1786 – 1817) fell sincerely and lastingly in love and their idyll gave birth to the first son of the Emperor in 1810, indirectly proving the inability of Josephine to give him an heir and causing, regretfully, the initiation of divorce proceedings. The Emperor was therefore not loyal to Josephine either, but he took great care to ensure that his wife knew nothing about his affairs. An attitude far removed from the Europeans kings of that time who maintained and sometimes allowed official wives and mistresses to tear each others to pieces. Always Bonaparte wanted his entourage and his family to be happy and not worried, a concern still marked by a bourgeois mind. In this new society oscillating between the customs of the Ancien Regime and a post-revolutionary modernity, Napoleon and Josephine formed a finally united couple who knew how to dominate the military, political and worldly scenes each by their talent: when he “wins battles, Joséphine wins hearts ”.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Long after their divorce, relations between Napoleon and Josephine remained marked by tenderness and sincere friendship. Bonaparte’s visits to Josephine at Malmaison were frequent. He always ensured that she lacked nothing (despite her bad habit of maintaining debts) and kept her title of Empress despite their divorce. She still cared for him, sought and facilitated his marriage to Marie-Louise of Austria (1791 – 1847) and sincerely congratulated her ex-husband on the birth of the King of Rome. Throughout his life and again in Saint Helena, the Emperor will fondly recall his memories of Josephine. If history has paid little attention to Napoleon’s second wedding, this is no doubt due to this singular relationship which in the 19th century was certainly as unusual as it seems, to our contemporary eyes, strangely ordinary …

The Death of Napoleon: such a big mystery?

When Napoleon died at St. Helena, the question of the causes of his death soon became a subject of debate. Cancer? Poison? These only evocations excite passions, because Bonaparte passed master in the art - beyond his death - to feed his own legend. Who would not try to imagine a romantic ending at the height of this extraordinary character?

Napoleon Bonaparte dies in St. Helena

On May 5th, 1821 at 5:49 pm, he died at the age of 51, the man who dominated most of Europe for a time. Arousing as much admiration, fear as hatred (the great authors such as Tolstoï, Germaine de Stael or Chateaubriand left us with strong memories), the exiled Emperor dies, however, after long suffering in his home in Longwood without even leaving a good word for posterity (his last words were confused and unintelligible).

Since March, Napoleon was bedridden and was less and less supportive of food, weakening rapidly. Persuaded for a long time that the evil that took away his father (a stomach cancer) would eventually defeat himself, he refused in the last month before his death most of the medications prescribed by his doctors. Nevertheless, the latter decided on May 4th to override the clear will of Napoleon I, agreeing with very poor common sense on the administration of a dose of calomel diluted in a glass of water. Only Dr. François Antommarchi (1780/89 – 1838) fiercely opposed it without winning any success. Louis-Joseph-Narcisse Marchand (1791 – 1876), faithful companion of the emperor, was charged with giving the secret remedy, mission which he acquitted painfully when Bonaparte, having drunk the contents of the glass said to him “with a tone of so affectionate reproach […]: “Are you misleading on me too?” Marchand, deeply moved, was indeed failing in his promise not to administer anything to him without his permission. The calomel certainly had an effect but probably not what we expected and so that May 5th late afternoon, Napoleon gave his last breathe. When midnight was over, the body was moved, then washed to purify it with the cologne that so he loved mixed with a little water from the Torbett Fountain.

Although the last will of the emperor was to be buried in France, the British government strongly opposed it through the governor of the island who however left free the relatives of the deceased to choose a place of burial at St. Helena.

Napoleon had discovered the Torbett fountain a few years before in the company of Henri-Gatien Bertrand (1773 – 1884) and recommended that: “if after [his] death, [his] body remains in the hands of [his] enemies, [they] should drop him off here.” The place thus imposed itself. The upholsterer Andrew Darling, who supervised the making of the coffins notes that he was told that “the coffins were to be the first in tinplate, upholstered in cotton-padded satin, with a little mattress and pillow in the back made of the same materials; the second of wood; the third lead; and finally a casket of mahogany covered with purple velvet, if it could be obtained.” Mahogany being a rare wood on the island, a table of this essence was sacrificed for the making of the last coffin.

After the autopsy of Napoleon, the heart and the stomach were placed in two vases of silver, filled with spirit of wine. These vases were hermetically sealed and placed in the coffin. The successive coffins were sealed in the same way. A lot of precautions were taken to make the tomb of Napoleon an impregnable fortress (one sank the cement in the pit before laying three heavy slabs and a gate of cast iron). The stele, however, remained silent since – without being a surprise – the English and French never agreed on the inscription, which would indicate the identity of the deceased as accurately as possible; each nation having a very firm idea of what it meant by “accurately”.

Napoleon prepares his legend

Long before he died, and even when he was at St. Helena, the emperor remained a fierce opponent of the English. The decision to isolate him in the middle of the Atlantic was therefore the least they can do and surely the British were not surprised to see the rare talent that Napoleon deployed to systematically undermine their authority. Emmanuel Las Cases (1766 – 1842) testifies in his memoirs of the treasures of inventiveness deployed by Bonaparte to give Europe the image of a dishonorable captivity, making the English revolting characters and completely devoid of humanity. Yet the reality was quite different and Napoleon was treated well despite some financial questions and etiquette that often put Bonaparte in a rage (the English in charge of his surveillance opposed him with consistency and determination the title of “general” when Bonaparte required that of “emperor” which he considered legitimate). Thus, our Corsican made for example sell his silverware on the place of Jamestown to make believe that he was at the last levels of poverty. The merchants returning from the Indies were, without them’s knowing, to play the role of gossips in Europe and to spread the infamous news. Jean Tulard, historian and specialist of Napoleon I, also recalls that Napoleon gave “an odious role to Hudson Lowe (1769 – 1844), who by the way, was not a monster of finesse”. While before embarking on Île d’Aix in July 1815, Napoleon I had refused several plans for escape, “it was better for his legend that he died, as he will say, murdered by the British government” recalls Pierre Branda, a French historian specializing in the Consulate and the First Empire.

What is Napoleon Bonaparte dead?

Unless one desecrates the tomb of the Invalides, will we ever know it with certainty? Nevertheless, the many accounts of his relatives and witnesses of his burial and his, to say the least, confrontational relations with his phlegmatic British jailers further guide the trail of the investigation to a death of pathological cause than to that of a perfidious poisoning. Of course, this last theory has something to seduce! Can a historical figure of this stature die stupidly from a failing stomach? It would seem, however, that we had to live with it.

Some people brandish the traces of arsenic detected in his hair but it is quickly forgotten that they were also found in those of Josephine and l’Aiglon. It is also unaware that in the 19th century arsenic was widespread in a role other than poison, so much so that it was often stored in the kitchen (and sometimes served as an unfortunate or criminal ingredient of an an undesirable gastronomy). It was used to make candles, cigarettes, tapestry pigments, dyes, paints and cosmetics. Many locks of hair of the imperial head were studied. It is almost systematically concluded that the doses were certainly high, but not for the 19th century. On the other hand, since the hair roots showed traces of arsenic, some people argued that this was proof that Napoleon had ingested the poison by food or wine. It had first been necessary for the poisoner to be a close relative of the emperor and to show extreme patience, for the man would certainly not die struck down by so small doses of arsenic, unless one envisages long-term poisoning. Unfortunately, the “French service” at the Longwood table (the dishes are presented on the table, people help themselves to dishes), it was necessary that the criminal also poisoned! As Jean Tulard slyly summarizes, either the poisoner was not good at it, or he still took a long time to kill him.

What about the body that was found almost intact in 1840 before his repatriation to the Invalides?

Arsenic, as well as an embalming, is famous for keeping the bodies in good condition. Once again, let us remember that Napoleon was buried, not in one, but in four hermetically sealed coffins. Most likely, a phenomenon of saponification (transformation of the flesh into adipocere) was favored by the absence of air and in this type of case, the good preservation of a body is quite often noted. Would one then enjoy to exchange the body of the sovereign by another less prestigious and bury in the Invalides a cook rather than an emperor? Again, there is no reason to believe this since the exhumation took place in the presence of many witnesses who had seen the imperial body 20 years ago. No one found fault with this, and, having passed the surprise of this astonishing preservation, they easily recognized the famous Napoleon.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

The question of the death of Napoleon I now unleashes the passions and testifies far less to the interest aroused by the emperor than his incredible talent for communicating, he who well before his death, was fully aware of the exceptional nature of his destiny. « My life, What a novel! » He said, dictating his memories to Las Cases during his exile in St. Helena. He could not have been more right: what better novels than those whose end maintains the mystery?

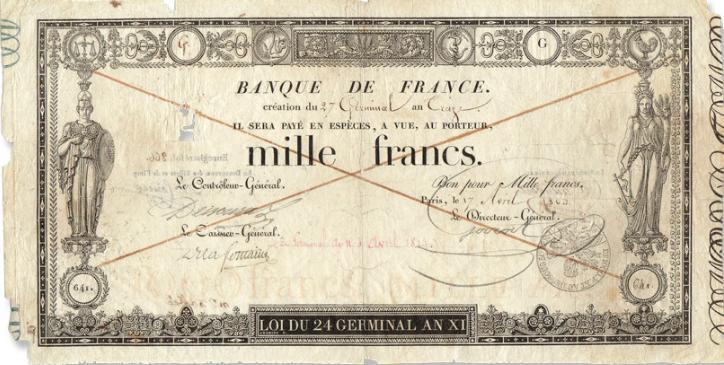

Creation of the Bank of France by Napoleon Bonaparte

In this very young XIXth century, the moribund economy post Revolution urged the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte to create the Bank of France January 18th, 1800 to promote the economic recovery of the country. The thrifty Napoleon wanted to create a stable and strong value in the heart of an institution that should not serve as a fund to the state but to promote its businesses.

A Stormy Political and Economic Context

The XVIIIth century was not beneficial to paper money. Scalded by the financial scandal of John Law (1671 – 1729) in 1720, the French had plenty of time to confirm their aversion to printed money when they were fooled a second time with brandishing revolutionary assignats that were nothing else than a lightning and spectacular inflation. Some, however, got rich. Among them, the Swiss financier Jean-Frédéric Perregaux (1744 – 1808). Precisely preceding the perpetual neutrality that will later make the pride of his native Switzerland, our Helvetian, who, before the Revolution, mixed with the world’s most popular aristocratic circles, was careful not to display too clearly his political opinions during the brutal change of regime. He preferred, as many at that time, to adapt them to the necessities of the moment. It was certainly the right move since the members of the nobility – fiercely attached to their heads – were quick to flee abroad taking care to carry with them a considerable part of the metal currency of the late Kingdom of France. A financial crisis hit the people, who – having nothing to fear for their own head – had everything to fear for their finances. In an extremely unfavorable economic climate, bankruptcies were numerous and internal trade paralyzed. The Directory was unable to remedy the problem in a sustainable way and it was not until the Brumaire coup (November 9-10th, 1799) to see the emergence of hope for a government stability essential to an economic recovery of the country. It was then that our dashing Swiss banker approached Bonaparte, the context and Napoleon smiling at him in concert.

Perregaux and a few banker friends (Le Couteulx, Mallet and Perier) first obtained the right to print bank notes for their own establishment named Caisse des Comptes Courants. They aim to collect the savings then hoarded by individuals and increase the amount of money in circulation. The Banque de France was created on 18th January 1800 by decree and quickly absorbed the Caisse des Comptes Courants. The very young Banque de France settled in the Hôtel de Toulouse, rue de la Vrillière in Paris, of course.

The first Consul wanted to be cautious and wanted to guarantee the stability and reliability of this new institution. The first issues of notes were thus guaranteed to find their equivalent in quantity of gold of the same value to any person who wished it. To proceed to the exchange, one should simply go to the Rue de la Vrillière. It was all about the reputation of the bank and its future, the first Consul was perfectly aware. The French, who enjoyed nothing less than being fooled three times in a row, were at first extremely suspicious. Then little by little, confidence returned. It must be said that Bonaparte’s personal, hard-hitting and irresistible involvement had something to do with this success. He placed some of his own funds in trust with the Bank and persuaded his family and relatives to do the same. The transaction, together with the capital contributed by wealthy shareholders, provided the institution with considerable capital, which was necessary to establish its essential importance. Soon, the Bank of France was the only bank authorized to issue monetary values hence its name “central bank”.

The main clients of the bank were ordinary banks, whose business was to lend money to individuals and businesses. The principle was therefore based on the promise of repayment made by the borrower to his banker, a promise referred to as a “bill of exchange”. At the same time, ordinary banks needed money to lend to new customers. They needed to have sufficient financial reserves to act without waiting for borrower clients to repay their debts. Ordinary banks turned to the Banque de France and bought him notes in exchange for the bills of exchange they had at their disposal. Naturally, the amount of money increased in the country and allowed to revive commerce and industry. In turn, the latter made profits that were inevitably taxed. Finally, the increasing value of taxes levied by the state allowed the country to get rich and the First Consul to finance his army (and not his campaigns).

The Franc Germinal, a Reliable Economic Value

The first notes issued by the Bank of France were of such value that they were not accessible to all. The 500-franc notes represented a little more than a year’s salary for a worker, and that of 1000 was equivalent to double the work, naturally. Not being convertible into gold elsewhere than in Paris, the notes further restricted the circle of lovers of bundles. These notes occupied so well the only high Parisian business that they had confused any merchant if a citizen would have the idea to give one of these papers to pay for a chicken (not far from becoming Marengo).

On the other hand, the memory of John Law and the revolutionary assignats remained tenacious, and the French countryside still preferred metallic values for their trade. The Revolution, by a law of August 15th, 1795 had already decided to replace the livre tournois by the “franc d’argent” but its will alone was not enough. Indeed, the fiery and first Republic had that in common with Josephine de Beauharnais (1763 – 1814) at the same time that no one had enough money – metal for one, ready for the other – to satisfy their needs. It was thus necessary to wait for the 7th germinal year XI (March 28th, 1803) to see reappear this franc which borrowed at its date of creation the name under which it will exercise until 1928 namely, the franc “germinal”.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Manufacturing and Security of Monetary Values

The first two banknotes put into circulation by the Banque de France represented considerable sums. From then on, everything had to be done to prevent as much as possible the appearance of false. The paper was first produced at the stationery of Buges in Loiret but it was quickly preferred that of the paper mill of the Marais at Jouy-sur-Morin. The addition of a watermark between the two sheets of paper constituting each note was one of the first security provisions. Then came the quality of the drawing for which Charles Percier (1764 – 1838) was called upon. This neoclassical architect who had distinguished himself in his achievements for financiers working alongside the First Consul was not long to be warmly recommended to the latter who praised his talents for a long time. The engraving of the matrix was entrusted to Jean-Bertrand Andrieu (1761 – 1822) who took as a support a steel plate to guarantee an inking always equal. Finally, the engraving typography returned to Firmin Didot (1764 – 1836) whose name is still well known today by lovers of prints and old editions. A stub was added, a dry stamp (embossing the paper obtained with a press) and a wet stamp (a technique for printing simultaneously on the front and back).

As for the symbolism of the chosen motifs, we find the strong influence of the Roman Empire (tinged with the neoclassical taste born from the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii in the XVIIIth century). Compass and square evoke the tools of the builders using geometry and architecture, while the rooster emblem of France rubs shoulders with the scale of Justice. The divinities represented are those that the great estates considered as constituting a strong state in the XIXth century: Vulcan for industry, Apollo for the arts, Ceres for agriculture and Poseidon for the colonial empire.

Metal coins are subject to the same concerns, both security and symbolism. The Republican motifs were replaced at the obverse of the pieces by Bonaparte’s bare-headed profile – whose engraver, General Pierre-Joseph Tiolier (1763 – 1819) painted the portrait – accompanied by a legend “Bonaparte First Consul”. The reverse was an olive crown, the face value of the coin and the legend “French Republic”. Of course, an imperial proclamation will be enough for the motives of coins and notes to be changed once more.

The creation of the Banque de France had a decisive impact on the country’s economy and its imperial expansion (although it did not finance them, the Emperor always defended it). Paper money improved, gaining security and discouraging counterfeiters. However, in 1959, the Bank of France issued a 100 franc note of Napoleon. This note made famous the forger Czesław Jan Bojarski (1912 – 2003) who made a specialty of the falsification of these “Bonaparte notes”. His mastery in this field is still unchallenged and unmatched. These fakes are now rare and expensive collectibles. An irony of history that certainly did not escape the Emperor if he had been alive to appreciate it.

The Renewal of Eau de Cologne

Previous century was not gentle with the Cologne. Mocked by a perfumery that swore by heady and featureless fragrances, the discreet Cologne was patient until it wins its spurs today. An esthete scent which prefers to accompany the toilet rather than oppose the perfume.

A Modern Water

The modernity of the cologne paradoxically resides in its age. For almost two centuries, the most chic bathrooms have given it a place of choice. The large retailers, without being able to seize it, damaged in the eyes of the public the elegant image of this fresh water. Designed from natural ingredients, Cologne meets our modern wishes to return to more simplicity. Down with formulas whose “active principles” are more incomprehensible than a quantum physics equation! Some citrus fruits, plants, a hint of spices make the recipe simple and yet refined with a water that is more for well-being than for appearance. The cologne is a selfish pleasure: it accompanies ablutions, this moment that prepares us to get out of our intimacy, venturing out in the open air. Its solar freshness awakens the senses and contact with water that is poured generously on the skin is not far to evoke the regressive games of water battles.

While perfumery likes to differentiate the woman from the man, the cologne does not care about gender. Establishing parity before the hour, it seduces us with this phlegm that prefers relaxation and hedonism to calculated seduction. It pleases by its simplicity which does not lack character, by its mischievous modesty. It is also this ingenuity that allows to offer a bouquet of shaded scents. The luxury industry made no mistake about it.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

A Refined Water

It is no longer a luxery firm that can refuse to have its own cologne. As a curious becomes an esthete as he goes along the subtleties of an art, many discover the elegance of the Cologne after having to face the impasse existing between a perfume which, on one hand, requires to get ones dressed to be worn and, on the other, the soft, unattractive smell of soap. Not everyone is Marilyn Monroe enough to think that Chanel No. 5 is suitable for all occasions. However, this is the first quality of the cologne: its lightness and simplicity make it the ideal fragrance in a daily where the perfume would be too pretentious. During relaxation moments, at the end of a sports session or simply for pleasure of contact with it, this water leaves on the skin a clean smell that resonates with lightness. The fresh notes exhale when we sprinkle it on our skin and its modesty leaves the wake back when ablutions are done. Cologne does not intend to perfume, it elegantly radiates a moment but knows the value of discretion. Napoleon, who copiously sprinkled himself with it, did not deny it that quality, he who had a horror of heady perfumes. The cologne awakened him without distracting him with catchy scents. Fresh without being banal, Cologne embodies an ideal of modernity where the sophistication is well matched with ingenuity.

New Year's Eve at Saint Helena

First half of the XIXth century still ignores the festivities of Christmas without being spared - at least in the wealthiest social classes - by distribution of gifts on New Year. This tradition of New Year's Eve also follows Napoleon in the latitudes of St. Helena. To offer New Year's gift meant to maintain his rank, a respect of etiquette rather than a necessity for the Emperor who did not confess fallen.

New Year's Eve at St. Helena.

Freshly landed at St. Helena on October 17th, 1815, Napoleon did not arrive alone. His little entourage knew the greatness of the Empire; it is certainly inconceivable for Bonaparte to make them witnesses of any decay of his person. As soon as he took possession of Longwood’s residence, the Emperor reinstated the strict etiquette that governed life in the Tuileries palace. But this etiquette that we think at first binding for his entourage was just as much for him. In applying it, Napoleon was well aware of the duties that he would impose upon him during his exile. On December 10th, 1815, day when he moved to Longwood, the imminence of the new year is only felt too much. But the perfidious Albion seemed to decide to insidiously disturb this tradition by choosing for land of exile that arid St. Helena on which no goldsmith or jeweler, artist or upholsterer had ever had the happy idea of establishing himself on the island. It is therefore in his personal belongings and the precious relics of his sumptuous past that Napoleon will draw to honor his little court.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

The gifts offered by Napoléon in Saint Helena.

We unfortunately do not know exactly the furniture and objects hastily carried away by Napoleon and his companions in exile when leaving for Saint Helena. And for good reason, most were purely and simply stolen by the faithful of the Emperor for the sole purpose of pleasing him. The journals and archives of those who had the honor of being admitted in the presence of Napoleon during his exile report some of the gifts he made on the occasion of the New Year. Emmanuel de Las Cases (1766 – 1842) notes in his diary on December 30th, 1815 that he was offered by the Emperor “a small gift, very slight indeed”, according to Napoleon himself, consisting of a monthly salary levied on a sum stolen from English vigilance. In January 1816 Bonaparte offered to Jane and Betsy Balcombe, daughters of William Balcombe (1777 – 1829), agent of the East India Company who welcomed Napoleon in his Saint Helena’s home at the end of 1815, two cups from the Cabaret Égyptien, pieces from the porcelain service of Sèvres which the Emperor held so much that he refused to use it on a daily basis for fear of breaking it.

The so-called “headquarters” (Quartiers Généraux) service – which did not know any Saint-Helene dishes for the same reasons as those which prohibited the use of the Cabaret Égyptien– was also cut off from certain pieces the following year when, for their presents, Napoleon offered to each Madame de Montholon and Madame Bertrand a plate from the precious service. That same month of January 1817, the Baron Gourgaud (1783 – 1852) reports that the Emperor offered more personal objects: to Madame Bertrand a candy box formerly offered by Pauline Bonaparte and to Gourgaud an spyglass that the Emperor held from the Queen of Naples, her youngest sister. To Bertrand he offered a game of chess and then played a party with him after the distribution of gifts. In January 1818, the New Year’s day is reduced to candies contradicting the very adventurous predictions of Madame Bertrand, who was expecting “sumptuous gifts” ; it is difficult to understand from where this idea came from given the geographical location of the island. These testimonies of happy moments illuminate the often dull idea that everyone has of Bonaparte’s exile. The habits dear to the Emperor remain despite the restrictions. Exile is thus colored with those charming and bourgeois moments that make daily life more bearable, revealing the intimate face of a Bonaparte whom appears as imperial as he is attentive.

Napoleon Bonaparte's emblems : between simplicity and erudition

Napoleon I forged his own emblems far from those too connoted of the Ancien Régime. The young Emperor intends to offer new perspectives to France history whose values are now supported by strong legible and historical symbols.

The antique influence.

Already consul Bonaparte (1799 – 1804) make clear, in his choice of furniture and art objects, an assurance which supported a broader thought in the matter of political will. Once Emperor, his architects and decorators Percier (1764 – 1838) and Fontaine (1762 – 1853) undertook to impose an official style flow with tastes of Roman antiquity. Massive mahogany and marble furniture evoked ancient temples, the luxurious sobriety of gilded bronzes borrowed the decorations of Republican Rome while the golden yellow, green, crimson and purple colors drew on the newly discovered frescoes of Herculaneum and Pompeii. It was at the dawn of his coronation that arose the thorny problem of the future imperial emblems. Everyone went there with his animal; the least chauvinists proposed the lion or the elephant while the most patriotic have their heart set on rooster. Others, probably more bucolic, suggested the oak. While the gallinace seemed to prevail for a time, it was ousted by the lion, itself scratched by the hand of Napoleon who preferred the eagle. The eagle which was also the emblem of imperial Rome elegantly associated the high antiquity and the traditional heraldry through the evocation of the Carolingian eagle.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Clear and erudite symbols.

If the eagle is emblematic of the reign of the Emperor, some symbols more directly evoke Bonaparte. First of all, let us quote the laurel wreath superbly presented during the coronation of the Emperor, where the latter’s head, laureled with gold leaf – art work of the great goldsmith Biennais (1764 – 1843) – gave this historical moment a grandiose character inherited from the ancient panache.

For this mythological attribute of Apollo celebrated in Rome both poets and victorious warlords: the evergreen foliage symbolized the immortality acquired by victory. Honorary and prestigious award attributed to the great military characters and, consequently, to the Emperor, the laurel wreath never lost its superb and reached the XIXth century with the same freshness, enriched only by the idealized glory of the Roman Empire.

Bees, for their part, were recognized for their organization, their hard work and their ability to sacrifice for the common interest of their hive. Nothing less than an ideal patriotic symbol, especially as they held from the Church a divine connotation (they carry the Word of God and wisdom to St. Ambrose and John Chrysostom). Moreover, it is believed (until recently) that the gold insects found in 1653 in the tomb of Childeric I – the not very famous founder of the Merovingian dynasty and father of Clovis – were bees. But it turns out that the latter were actually cicadas. Either, Childéric’s bees were considered as the first emblem of the sovereigns of France. It was enough to sit our Emperor in the natural continuity of ruling power without vexing the religious power. Thus linked to idealized antiquity and to history, if not entomological, at least French, Napoleon Bonaparte had only to engrave his name in history. What he did literally. His number (the letter N) was indeed carved on the facades of the Louvre. Nevertheless, the avenging Bourbon, once returned to the throne, hastened to hammer the imperial letter wherever it was. Thus, most of the “N” that adorn the Louvre today are those of Napoleon III and not those of his uncle emperor. Finally, last symbol and not least, the crowned “N” found on the coins of that period. This crown, now preserved in the Louvre, was only used on the coronation day. Called the Couronne de Charlemagne, it presents a timeless medieval look with eight half-arches of gold adorned with cameos; a globe surmounted by a cross completes the work drawn by Percier. Placed above the head of the Emperor, already surrounded by laurels, the crown tied ancient glory, history and patriotism all the ceremony long.

This set of symbols produced a simple speech, clear and powerful as the juxtaposition of its elements instantly evokes, and still does today, the Emperor Napoleon I.

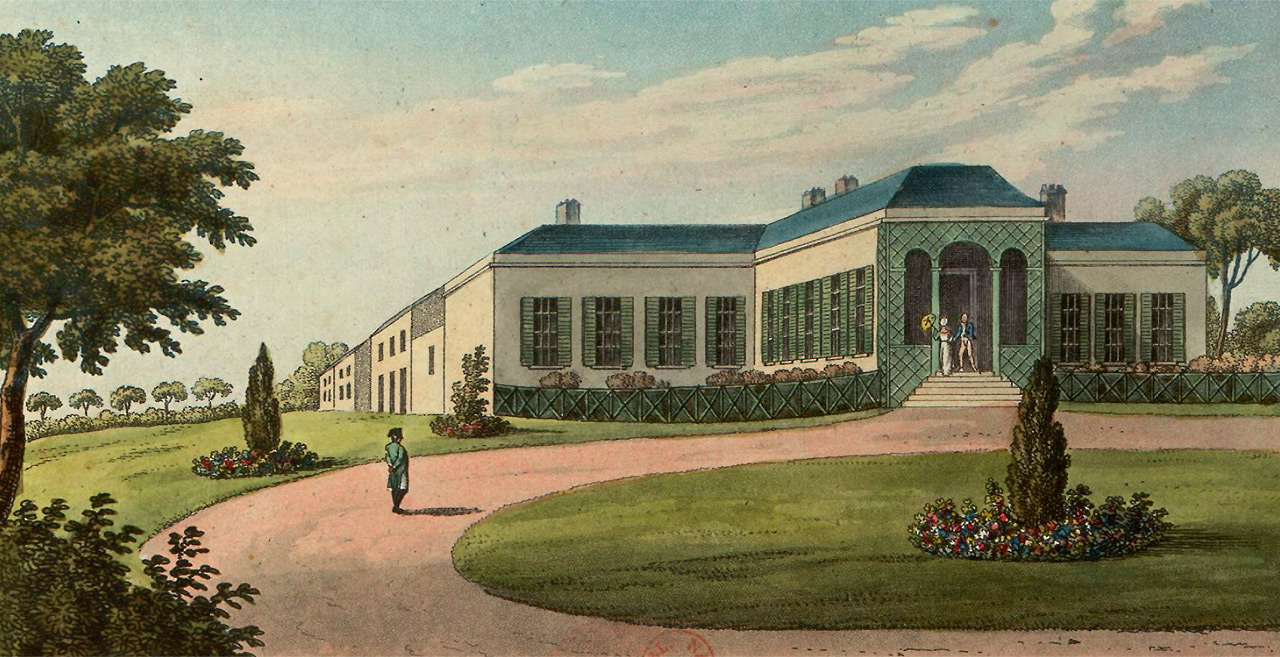

Longwood House

When Napoleon Bonaparte arrived on October 17th, 1815 at his place of exile while his residence at Saint Helena was not yet ready. He moved to Longwood two months later on December 10th, 1815 and remained there until his death on May 5th, 1821. Between piteous furniture and glorious memories of the past, the interior of this dilapidated Longwood was both a disrespectful prison and cradle of the myth birth.

Between respect and bitterness: the British reluctance to keep its commitments to its famous prisoner.

Longwood House is from Napoleon’s arrival a second rate house poorly built where water seeps everywhere. During the 68 months in which Bonaparte was confined there, many rotting pieces of furniture were burned, repaired or redone. Far from the vast and comfortable palaces of Saint-Cloud or the Tuileries, this house of 150 m2was, in the opinion of all, as deposed he was. Longwood was divided into an antechamber, which became a billiard room in 1816 (Napoleon nevertheless used it as a “topographic salon”), a lounge, a dining room, a study, a bedroom, a library, and a bathroom with copper tub. The English, who were obliged to cover the expenses of Bonaparte’s imprisonment, did not shine here by their fair play. In addition to the dilapidated decay of Longwood, the attentive observer will note in Sir George Cockburn (1772 – 1853) – in charge of finding all the necessary furniture – a certain resentment towards our Corsican since he acquired at a low price from the local disparate furniture that they themselves held thanks to their haggling with the British, Dutch, Portuguese and American ships passing on the island for supplies. Some of the finest furniture on loan from the East India Company came to enrich the house interior, as well as some of those specially designed by George Bullock (1778-1818), a London cabinetmaker, originally intended to furnish Longwood New House, a residence under construction when Bonaparte arrived but in which he will never live.

This shameful disrepair in the eyes of the French as of those of several English visitors nevertheless found a major adversary in the strict imperial etiquette applied throughout the estate, in the splendor of the furniture and objects brought back from France and in the very dignity of the imperial prisoner.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Luxurious reminders of the reign, a fertile ground for the birth of the Napoleonic myth.

Sir Hudson Lowe (1769 – 1844), governor of the island from 1816, was the first offended that the rank of the general was not respected in the layout of Longwood itself. By way of compensation, he offered Bonaparte a large billiard table and two important globes, one terrestrial, the other celestial. Then, on the ordinary wooden furniture, on the mahogany consoles, the relics of the Napoleonic reign helped to hide the British failure. The diaphanous marble bust of the King of Rome, sparkling pendulum in gilded bronze and enamel, majestic eagle sculpture in silver, luxurious gold sword and damascened steel – a unique artwork of Biennais (1764 – 1843) – lend their magnificence to the embellishment of an everyday life punctuated by the writing of Napoleon’s memoirs.

In the uses, the particular service of the Emperor realized in the finest porcelain of the imperial manufacture of Sèvres, the elegant crystal glassware or even pieces of the coffee service called “Cabaret Égyptien“, also of the manufacture of Sèvres and which Napoleon appreciated so much, allowed to establish the dignity of a man who intends to remain sovereign until his last breath. Witnesses of his past glory and his myth to be born, his campaign bed, “this old friend he preferred to any other” according to Louis-Joseph Marchand (1791 – 1876), in which he breathed his last, is still exhibited in Longwood while his beloved Athenian is now presented at the Louvre.

Athenian of Napoleon Bonaparte

While France leaves Ancien Regime to turn in a 19th century full of promises, habits regarding hygiene change slowly. Water takes a new place at the center of daily custom. Vases, basins and Athenian enhance water making it a symbol of freshness, purity and simplicity essential to the most refined people.

Simple use in a sophisticated furniture

We know the meticulous care that Napoleon took to his personal hygiene. In life as in war he promoted efficiency without losing sight of the importance of etiquette: if his ability to live as a soldier made him popular with his troops, his attachment to objects of power made him an experienced politician. This Athenian, a luxury basin for ablutions, admirably fulfilled these two requirements of efficiency and representation. He found it so much to his liking that from the Tuileries at the time of French Consulate to St. Helena, the imperial Athenian will follow the Emperor to the peaks at his fall. On drawings by Charles Percier (1764 – 1838), the tabletmaker Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764 – 1843) put all his talent at the service of this luxury furniture made of bronze, silver and yew. Elegant gilt bronze swans display majestic wings to support a silver basin carved with reed patterns.

The silver ewer used to pour the water for Napoleon’s ablutions rests on the tablet decorated with dolphin at its angles. While fine bees – emblems of the Emperor – in gilded bronze adorn the Athenian, dolphins, reeds and swans evoke the aquatic world, the freshness of the lakes and rivers, poetic metaphor of the use intended to this piece of furniture.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Such a sweet theft

In his Mémoires, Louis-Joseph-Narcisse Marchand (1791-1873), first manservant of Napoleon tells how, at the end of the Cent-Jours (June 1815), he stole the Athenian at the Palace of the Elysée – furniture that would have been inevitably confiscated – before the deposed Emperor was exiled to St. Helena. Marchand testifies “The Emperor had praised this piece of furniture for his use, I knew what privation it would be for him, he liked after his beard, to put his face in a lot of water […] in the thought of being pleasant to him, I had it brought to my carriage, and I covered it with my cloak so as not to arouse the attention of the passers-by of Paris and on the road.”

There is no doubt that Napoleon praised the attentiveness and delicacy of his faithful manservant! The harshness of island life was certainly softened by the use of this magnificent tripod basin, a practice which, as we know, Bonaparte systematically accompanied with Cologne, which he was so fond of and use to say, at least, in a gargantuan way.

The Athenian today preserved in the Louvre Museum was one of the rare goods for which Napoleon was fond of. He testifies it in his will where “the inventory of [his] effects that Marchand will keep to give to [his] son” states that he bequeaths to the King of Rome (1811 – 1832), his son “[his] sink, his water pot and his foot.”

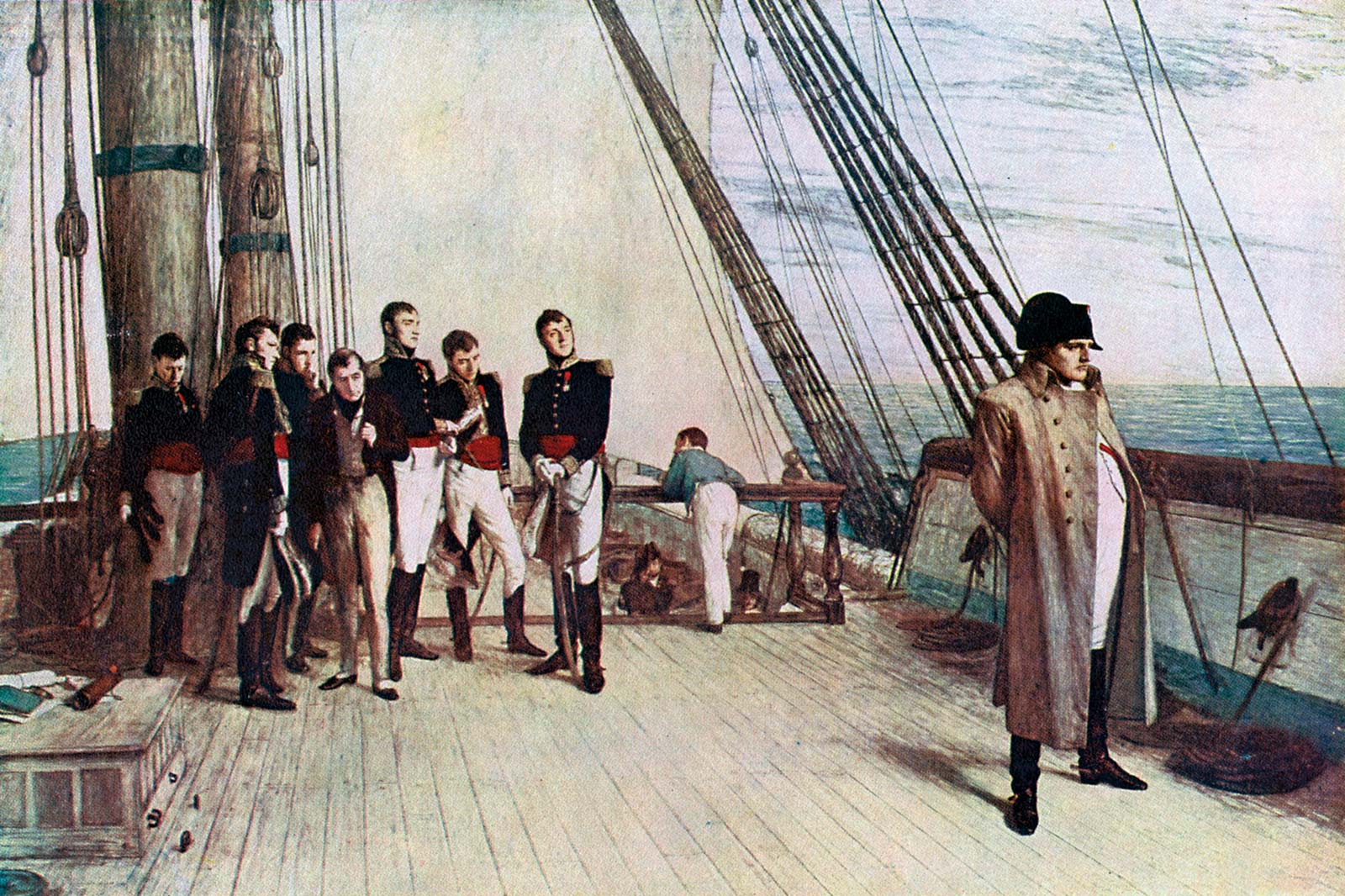

The Arrival of Napoleon at St. Helena

Following the Hundred Days (from March to July 1815) - the short period in which Napoleon regained power after his second abdication - the decisive defeat of Waterloo (June 22nd, 1815) is paid a heavy price by victors. The casualties were enough to prove that Napoleon represented a threat to future European peace unless he was sent to a reclusive land far from everything. For the Emperor, even vanquished, seemed to have the same determination as the phoenix to reborn from ashes.

Exile Required by the European Powers.

While the defeat of Waterloo sign the imminent end of the Hundred Days, Napoleon surrendered voluntarily to the English who has the responsibility to choose his place of exile. While the fallen Emperor hopes to be sent to the United States, Great Britain is responsible for keeping him in good guard before the place where he will be sent is determined. For the allies and signatories of the Treaty of Paris (which acts the first abdication of Bonaparte on February 10th, 1763) are united in their intransigence in sending Napoleon where he will be totally and certainly unable to return to Europe to sow – according to their fear – disorder and chaos. At the same time, the allies formed by the European rulers do not savour the fervent support received by Napoleon during this last period.

Its perfume inherited from the French Revolution does not, indeed, have the leisure to please them which is confirmed by Bonaparte’s support everywhere in Europe. This support sees in this general having started with nothing one of the most important characters of his time, a precursor for a “modern administration and justice, for the meritocracy and the revolutionary principle of equality before the law. (Alan Forrest, in Napoleon at St. Helena, The Conquest of Memory, Gallimard / Army Museum). In this context, the choice of St. Helena does not appear as obvious as a relief. Behind an altruism of facade that justified this choice by a healthy climate and a distance that would to treat fallen Emperor with a particular indulgence, hides a real desire to isolate the general on a land surrounded by much more waves than his native corsican island.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

The landing of the Emperor at St. Helena.

On the morning of July 15th, 1815, Napoleon embarked on the Bellerophon flying the British flag bound for Plymouth in the south of England, from which he left on Northumberland on August 7th for St. Helena. His journey lasts several months and he finally arrives on the island on October 17th. The Longwood estate which has been attributed to him is not yet ready and he must, pending the end of adjustments, remain in the property of William Balcombe (1777 – 1829), agent of the East India Company with whom he quickly becomes friends. On December 10th, 1815, the deposed Emperor can finally move into his last home in Longwood, a house without comfort that the small circle of his faithful will strive to soften until the last breath of the general.

In order to please him, domestic service is quickly put in place. The interior and exterior service is provided by Louis-Joseph Marchand (1791 – 1876), Napoleon’s first dedicated and faithful manservant since the age of 20. He is assisted in his task by the Mamluk Ali (1788 – 1856) with whom he befriended. Butler Cipriani and chef Michel Lepage provide the food service while four manservant maintain fires, light candles, set tables and meet the demands of the Emperor and his officers.

Although his entourage is devoted body and soul to his well-being (even to recreate his cologne!), Napoleon can not ignore the control of his mail, his strictly supervised walks or the supervisory of his House spending. Bonaparte died on this isolated island in May 1821 at the same time that his legend was born on the continent that had exiled him.