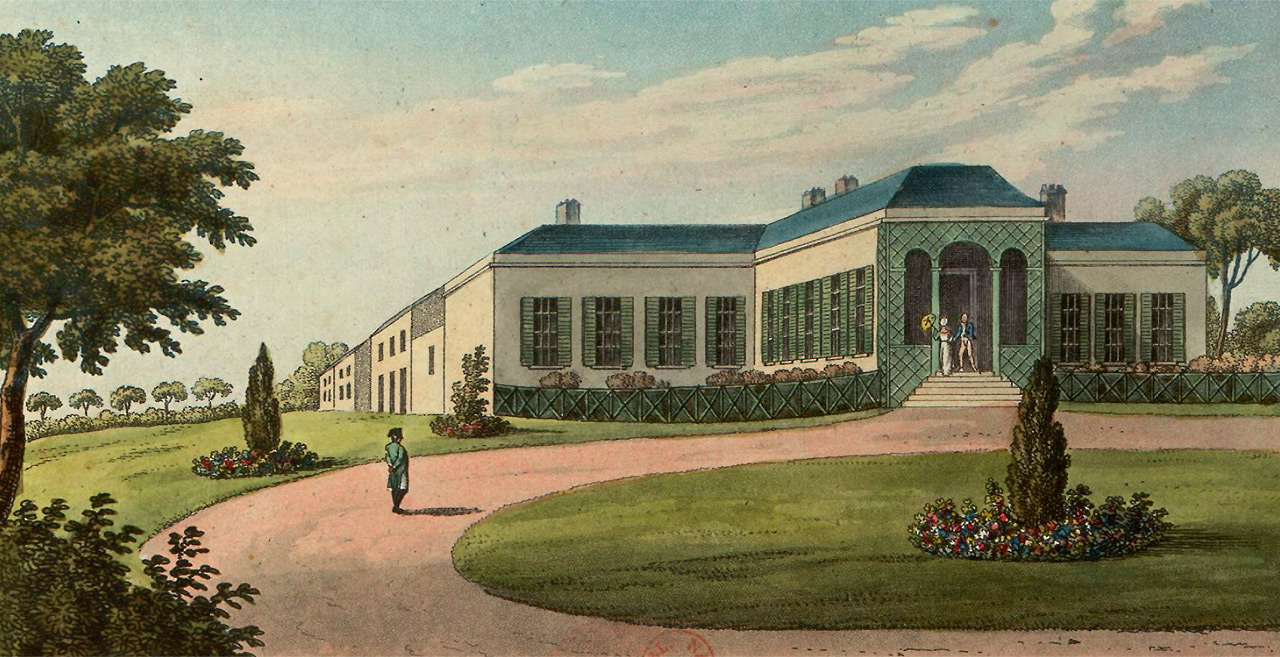

When Napoleon Bonaparte arrived on October 17th, 1815 at his place of exile while his residence at Saint Helena was not yet ready. He moved to Longwood two months later on December 10th, 1815 and remained there until his death on May 5th, 1821. Between piteous furniture and glorious memories of the past, the interior of this dilapidated Longwood was both a disrespectful prison and cradle of the myth birth.

Between respect and bitterness: the British reluctance to keep its commitments to its famous prisoner.

Longwood House is from Napoleon’s arrival a second rate house poorly built where water seeps everywhere. During the 68 months in which Bonaparte was confined there, many rotting pieces of furniture were burned, repaired or redone. Far from the vast and comfortable palaces of Saint-Cloud or the Tuileries, this house of 150 m2was, in the opinion of all, as deposed he was. Longwood was divided into an antechamber, which became a billiard room in 1816 (Napoleon nevertheless used it as a “topographic salon”), a lounge, a dining room, a study, a bedroom, a library, and a bathroom with copper tub. The English, who were obliged to cover the expenses of Bonaparte’s imprisonment, did not shine here by their fair play. In addition to the dilapidated decay of Longwood, the attentive observer will note in Sir George Cockburn (1772 – 1853) – in charge of finding all the necessary furniture – a certain resentment towards our Corsican since he acquired at a low price from the local disparate furniture that they themselves held thanks to their haggling with the British, Dutch, Portuguese and American ships passing on the island for supplies. Some of the finest furniture on loan from the East India Company came to enrich the house interior, as well as some of those specially designed by George Bullock (1778-1818), a London cabinetmaker, originally intended to furnish Longwood New House, a residence under construction when Bonaparte arrived but in which he will never live.

This shameful disrepair in the eyes of the French as of those of several English visitors nevertheless found a major adversary in the strict imperial etiquette applied throughout the estate, in the splendor of the furniture and objects brought back from France and in the very dignity of the imperial prisoner.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Congratulations!

You are now registered to our Newsletter.

Luxurious reminders of the reign, a fertile ground for the birth of the Napoleonic myth.

Sir Hudson Lowe (1769 – 1844), governor of the island from 1816, was the first offended that the rank of the general was not respected in the layout of Longwood itself. By way of compensation, he offered Bonaparte a large billiard table and two important globes, one terrestrial, the other celestial. Then, on the ordinary wooden furniture, on the mahogany consoles, the relics of the Napoleonic reign helped to hide the British failure. The diaphanous marble bust of the King of Rome, sparkling pendulum in gilded bronze and enamel, majestic eagle sculpture in silver, luxurious gold sword and damascened steel – a unique artwork of Biennais (1764 – 1843) – lend their magnificence to the embellishment of an everyday life punctuated by the writing of Napoleon’s memoirs.

In the uses, the particular service of the Emperor realized in the finest porcelain of the imperial manufacture of Sèvres, the elegant crystal glassware or even pieces of the coffee service called “Cabaret Égyptien“, also of the manufacture of Sèvres and which Napoleon appreciated so much, allowed to establish the dignity of a man who intends to remain sovereign until his last breath. Witnesses of his past glory and his myth to be born, his campaign bed, “this old friend he preferred to any other” according to Louis-Joseph Marchand (1791 – 1876), in which he breathed his last, is still exhibited in Longwood while his beloved Athenian is now presented at the Louvre.

Marielle Brie

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».