What were we drinking at Napoleon's table?

After giving pride of place to gastronomy under the Empire and Napoleon Bonaparte's favorite dishes, let's take a look at what we drank at his table. Unsurprisingly, wine lovers will surely prefer Joséphine's eclectic and exotic tastes to Napoleonic frugality!

What was Napoleon Bonaparte drinking? We know that he is little concerned with good food and more sensitive to the simplicity of family or military gastronomy. If the man was no more fond of wine than of refined dishes, he nevertheless had his preferences. As for the guests at his table, they had no fear of dying of thirst: the Malmaison cellar concealed treasures carefully selected by Joséphine de Beauharnais.

Napoleon Bonaparte, a reasonable drinker

As a man of habit, Bonaparte almost always eats the same thing and drinks the same Burgundy wine every day, this Chambertin which he cuts with ice water. Constant (1778 – 1845), Napoleon’s valet from 1800 to 1814 reported this habit:

The Emperor drank only Chambertin and rarely pure.

The fact is confirmed by Mademoiselle Avrillion (1774 – 1853), Joséphine’s first maid. The ideal mixture of wine and water balances out half of one and half of the other. At the rate of a 50cl bottle for lunch and dinner, the bottles had to be kept ready in all the places frequented by Bonaparte. The habit began as soon as he was general since it was necessary to take cases of this Burgundy to Egypt. If the campaign was victorious for the future First Consul, it was disastrous for his bottles which hardly withstood temperature changes. Back then, sulfur was not a part of regular wine production, and unfortunately its absence often turned wine into vinegar.

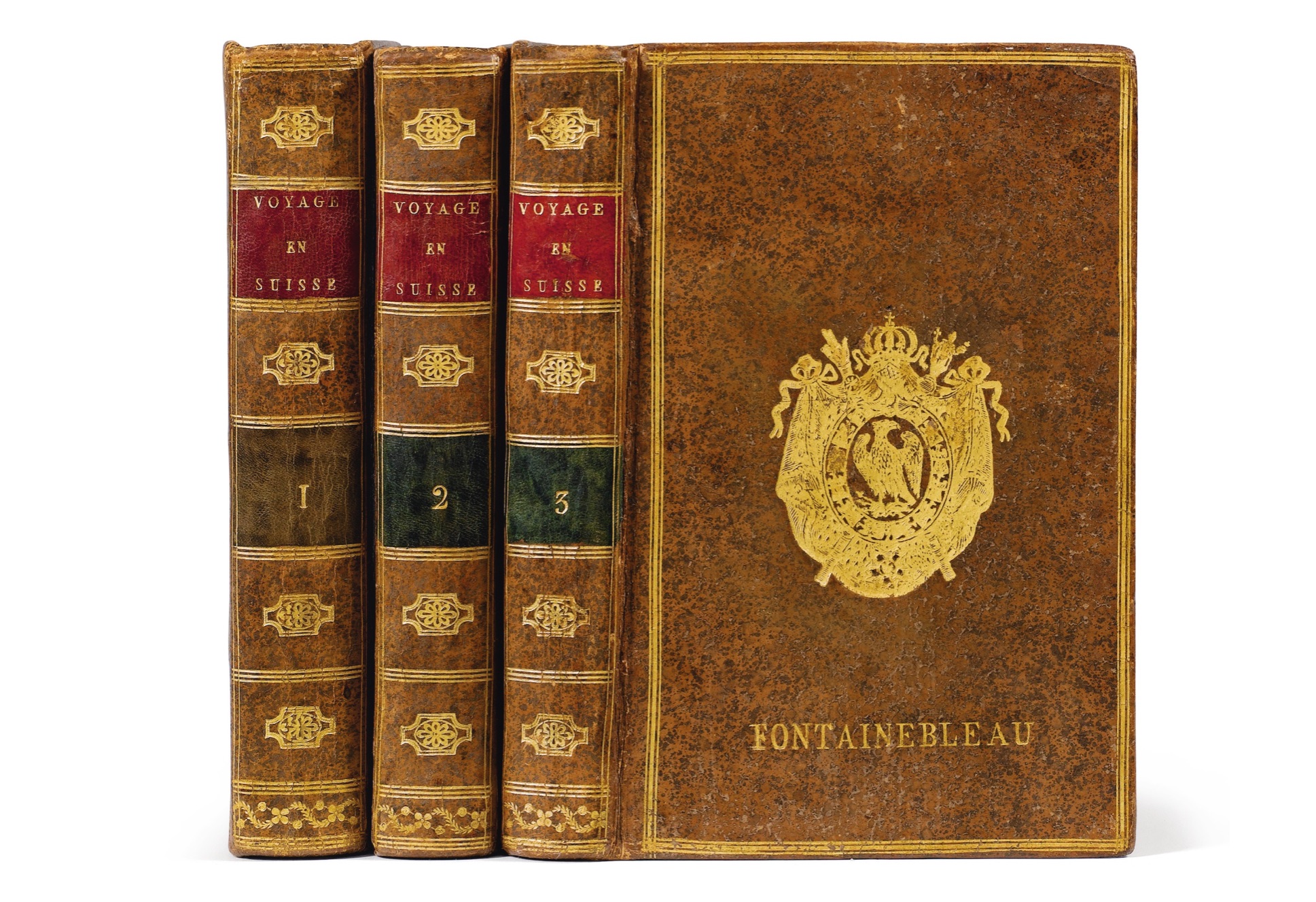

Under usual conditions, however, we were already beginning to age the nectar using opaque glass bottles whose cork stoppering more securely preserved the integrity of the beverage. Usually, we served Napoleon Bonaparte and then Napoleon I – both maintaining perfect linearity in their habits – a 5 or 6 year old Chambertin which was supplied by the Maison Soupé et Pierrugues located at 338, rue Saint-Honoré in Paris. The merchants’ mission was to provide all the imperial residences and “on the battlefields, the sons of these gentlemen took turns following the Emperor”, testifies the valet Constant. The art of the table adopting the Russian service and abandoning the French one, the attention to the bottles was very different from the previous century and the wine was put in glass bottles manufactured in Sèvres and marked with the crowned N.

I cannot live without champagne, in case of victory I deserve it, in case of defeat I need it.

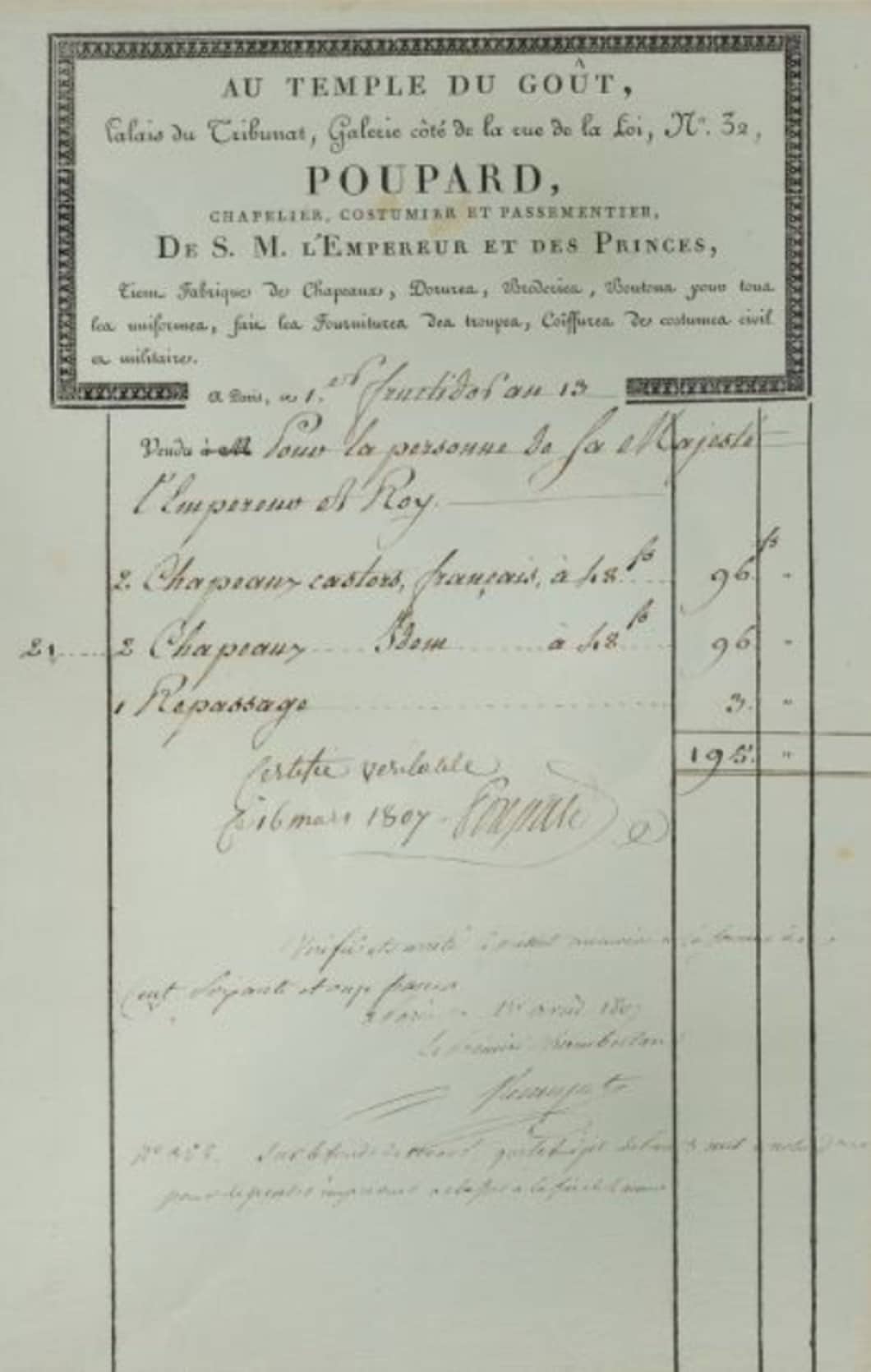

We lend this quote to Napoleon Bonaparte. And no doubt he said it. His taste for frugality is well established and champagne is one of the rare gastronomic pleasures that he truly appreciates. Proof of this is in the archives of the Moët house which keeps the accounting records of the orders placed by the famous Corsican. The very first is in the name of Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of Paris on the date of 27 Thermidor year 9 (August 15, 1801, the birthday of his 32 years!) then another passed in 1803. Once Bonaparte became Napoleon I, the orders were sent to the Emperor and his family. A few months before the Battle of Austerlitz, at the beginning of September 1805, an order from the Emperor was sent to Strasbourg and undoubtedly it was preparing without knowing it to celebrate a great moment in history. Joséphine and Jérôme Bonaparte also meet in the accounting records of the famous champagne house.

At the head of the latter, Jean-Rémy Moët, then mayor of Épernay, does not seem to have met the Emperor who came to his city only attracted by the fine bubbles. Napoleon I would have sympathized with this man who welcomed him to his home and who received, from the Emperor’s hand, the Legion of Honor.

Joséphine and the cellar of wonders of Malmaison

The inventory of Joséphine de Beauharnais’ cellar in 1814 reveals the extent of the refined taste of the owner of the Malmaison. More than 13,000 bottles are listed on the death of the former empress with prominently many sweet wines from vineyards ranging from Andalusia to Portugal, passing through the coasts of Languedoc, the islands of Madeira and the Canaries. These wines, appreciated for their sweetness, were served during afternoon snacks or for dessert at the many receptions and meals organized by Joséphine.

A major meeting place for the elite and those close to the imperial family, the reputation of the Malmaison table has stood the test of time. It is undoubtedly a must in the history of French gastronomy and tableware. Joséphine de Beauharnais, expertly advised by the best palates of the Empire (Cambacérès and Talleyrand in the first place), shone with a daring choice of prestigious wines and exotic alcohols, a memory of her native Martinique.

Bordeaux and Burgundy wines, champagnes, Côtes du Rhône and Rhin, Muscats from Lunel and Roussillon, vermouth, Italian and island liqueurs were regularly served at the table. Especially rum was a Creole eccentricity that delighted guests, especially when it was served as a punch, a drink already fashionable in the 18th century but which became essential under the Empire. Joséphine loved it, having it scrupulously prepared with the five essential ingredients then: tea, sugar, cinnamon, lemon and rum. Reason why the punch bowl was part of the… tea sets!

To please the ladies, the punch was served frozen. Some say that it is in Procope restaurant that it was drunk thus first because this very fresh punch attenuated the taste of alcohol and thus pleased more ladies. The story does not say if Josephine drank it like this at bedtime.

Because if the Empress was not a big consumer of alcoholic drink, she often drank, before sleeping, a small glass of punch. No wonder, because this beverage was credited with ensuring a smooth and peaceful sleep. There was nothing incongruous about the presence of a punch bowl in a bedroom at the start of the 19th century. Remember that those days are over, this is no longer the case today and that it would be the worst taste to replace your blanket with a bottle of rum, even if it was embellished with sugar and spices.

When Bonaparte was exiled to Saint Helena in 1815, his daily life was naturally upset. His Chambertin could not stand the trip and the English served him a claret that the fallen Emperor did not appreciate. Sometimes we see him working out a few negotiations to exchange a few bottles for Burgundy, without success.

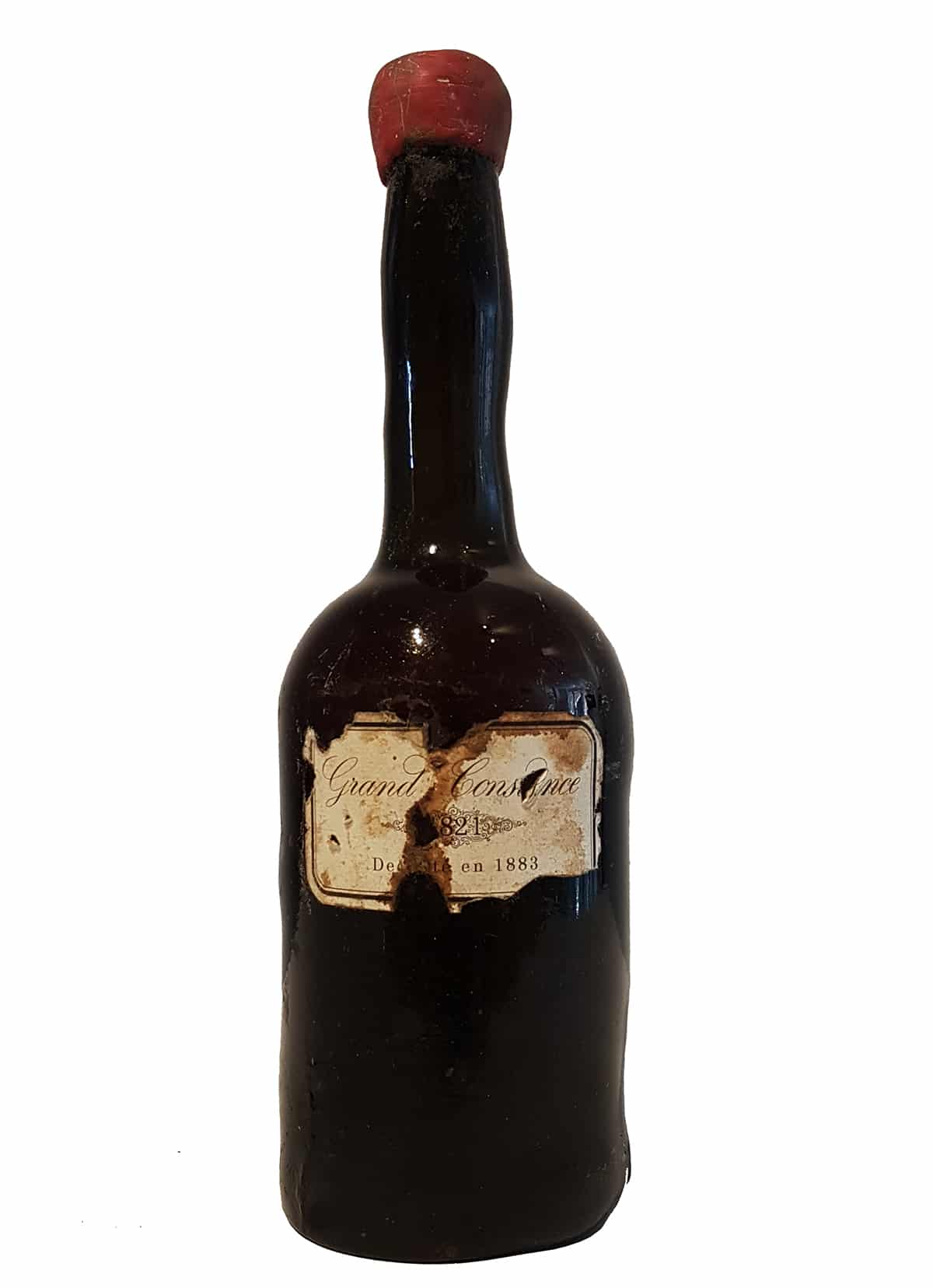

A wine from the Constancia vineyard, the Grand Constance, which is still known today as “Napoleon’s wine” is brought from Cape Town for him. In 2016, a bottle of Grand Constance dated 1821 and intended for Bonaparte was sold for € 1,550. A fragile memory of the daily life of the last days of the Emperor.

The Bicentenary of the death of Napoleon Bonaparte

The bicentenary year of the death of Napoleon Bonaparte has not yet been inaugurated as the controversy is already raging. What do we reproach the Emperor Napoleon I? Between black and golden legend, Bonaparte is a complex character, a historical object that it would be wrong to judge in the light of the present.

Are we aware of the influence Napoleon exerted on french lives on a daily basis? The Civil Code is undoubtedly the most immediate example, but the baccalaureate, the Legion of Honor and the Louvre as we know it today are Napoleonic works. The glory that this famous French figure – during his lifetime – on a world scale was so great that we still find it difficult to imagine it. It is undoubtedly this glory which is worth moreover to Napoleon so many criticisms: close enough to us and documented so that we can dare the comparison with our contemporary time but sufficiently distant so that it is tempting not to see anything other than the aura of the man who created his own myth. Napoleon Bonaparte did not have the glorious comforts of ancient heroes.

Napoleon Bonaparte and the restoration of slavery

The rise of Bonaparte is not the work of a single man. Neither did his rise to power. The coup d’état of 18 Brumaire Year VIII (November, 9th 1799) drew on the finances of businessmen as well-off as they were worried about the country’s political instability. Their support does not know philanthropy and naturally implies that they gain a voice in the decisions that will be taken subsequently. Once Napoleon Bonaparte appointed First Consul (20 Brumaire), requests for the reestablishment of slavery abolished in 1794 in the French colonies became regular and insistent. Until 1802, Bonaparte did not give in:

We must not take freedom from the men to whom we have given it.

Alas, he will end up going back on his words. Following the peace of Amiens in March 1802, France recovers its colonies of Martinique, Tobago and Saint Lucia. However, the abolitionist law of 1794 had not been applied either in Reunion – which had hampered its application – or in Martinique where a royalist insurrection had led to an agreement of submission to the English royalty before the latter conquered the island. .

The law of May 20th, 1802 concerns the territories which had not applied the abolitionist law of 1794. Thus, the territories recovered during the peace of Amiens were in theory not concerned by this law. Nevertheless, slavery was reestablished in Guadeloupe by a decree of July 16th, 1802 – the original of which, discovered in 2007 at the French National Archives, was presented on the occasion of an exhibition commemorating the bicentenary of the death of Napoleon I in 2021. The presentation of this document to the public for the first time is an important position taken to refine an often distorted or poorly understood dimension of Bonaparte’s reign and its consequences on human rights throughout the 19th century. In Guyana, slavery was reestablished in April 1803. General François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (1743 – 1803), will participate in the independence of part of Santo Domingo which will become Haiti on January 1st, 1804.

The massacres perpetrated by French troops on black insurgents in Guadeloupe and Martinique to regain control are among the bloodiest acts of Bonaparte’s reign. Let us add that the abolition of slavery in France will have to wait until 1848 before being final. The beginnings of the reign of the future emperor thus make France the only country to have re-established slavery. A French cultural exception whose history would have gone well.

Napoleon Bonaparte, the misogynist?

The Ancien Régime aristocracy – the highest in particular – stood out in the 18th century as one of the few circles in which misogyny had little or no influence. The revolutionaries held it against them and the accusations wept. The reproaches were all found and the aristocrats to have effeminated, to have become weak as one imagined then the natural inclination of the women. Revolution in opposition to the Ancien Régime therefore wanted to be virile. Bonaparte, like all the men of his time, had no other idea of the masculine ideal: solid, strong and determined, adjectives deliberately removed from the feminine sphere too superficial and fragile to interfere with serious subjects. The exuberances of Les Merveilleuses at the end of the 18th century sound the death knell for a feminine presence accepted and admired outside the domestic space, a last jolt before a 19th century of feminism that appalling in the eyes of our young 21st century.

Once the Directory and even more the Empire were established, the nineteenth century pushed revolutionary virility further by drawing fairly firmly into male and female genders which, even at the beginning of the twentieth century, we had all the trouble in the world to get rid of.

The Civil Code, a famous work of the Napoleonic reign, then stands out in our eyes as the assumed and satisfied contemptor with the condition of women and contemporary opprobrium. And for good reason, the text does not have a feminist soul. Yet it would be perfectly anachronistic to imagine that the man of the beginning of the 19th century allowed Bonaparte to impose an idea of woman. Misogyny is neither pervasive nor new.

If a few very rare feminists made their voices heard during the French Revolution, it is perfectly unthinkable to imagine giving a woman the responsibilities of a politician. In this sense, Napoleon Bonaparte is no more misogynistic than his male contemporaries (but is undoubtedly more so than his female contemporaries). In drawing up the Civil Code, Bonaparte kept in mind his primary concern: to protect the family unit, the model of which was necessarily patriarchal. A delicious irony when you know the central and authoritarian place of Letizia (1750 – 1836) in the clan of the famous Corsican.

Man must therefore be at the center of the family, he is its central pillar. He is required to be respected and to protect women and children. The failings of the head of the family are legally reprehensible, but those of women are even more so. The Civil Code confines the woman in the place of a minor individual placed under the tutelage of her husband: “The husband owes protection to his wife, the woman obedience to her husband. The woman is considered “weak and dependent”, like a child. This is why the rights of women, if they are considered sacred, cannot be entrusted to her because her very nature does not allow a woman to exercise them reasonably. Jacques de Maleville (1741-1824), one of the drafters of the Civil Code, likes to remind women of the “feeling of their inferiority” and “the submission they owe to the man who will become the arbiter of their destiny. However, sad reassurance, a man cannot divorce a woman over the age of 45. A precaution that stems from the duties of the husband who are required to ensure the protection of his wife. There is no question therefore of abandoning the latter if by chance the desire took you to find the titillating sensations of youth.

Once again, let us note the irony which forces Napoleon I to circumvent his own law to marry Marie-Louise of Austria (1791 – 1847). The protection of children is also a concern which is important to Bonaparte and we have always inherited many of its provisions today.

For a man who judged the break-up of the family unit as a disorder harmful to the good running of society, his private life was the perfect counterexample, a total fiasco which is surprising and which reveals a large part of the ambivalence of the Napoleonic myth.

Married to a widow mother of two, he finally manages to divorce while Joséphine is 46 years old. His second wife Marie-Louise gave him a son who barely knew his father and who was left with terrible loneliness until his death at the age of 21. Two other children of Napoleon will live without ever being recognized by their father, then Bonaparte will die in Saint Helena, alone and without any member of his family by his side. The break-up of the family unit he feared so much could not be more complete.

So the Civil Code is, without doubt, severe with the female condition; but it is not an ideology personal to Napoleon Bonaparte. Because the fall of the Emperor does not announce improvements for women whose lower status is maintained under the Restoration.

Of course, some female voices contemporary with the Napoleonic work speak out against such considerations, but they are rare and require a certain social status to be heard. The rare women journalists, those “blue stocking” that men despise, try to make themselves heard in a journalistic and literary world entirely in the hands of men. The task is difficult and painful to say the least. Only the figure full of panache and the dazzling fame of Madame de Staël (1766 – 1817) is offended openly about what is inflicted on women. Her character and intelligence dissuaded even Napoleon from replying, he who said of her:

I have four enemies, Prussia, Russia, England and Madame de Staël.

May 5th, 2021 inaugurates the bicentenary of the death of Napoleon Bonaparte, who died in Saint Helena on May 5th, 1821. If criticism is raised everywhere as to the celebration or not of the death of this character and the commemoration of his influence in the history of France, divisive opinions still carry the debate to the confines of an absurdity which sometimes comes under artistic performance.

To commemorate does not mean blindly praising or shooting on sight. The virtue of the debates between historians and specialists in Napoleonic history with argued, documented and posed speeches are undoubtedly the best answers to bring in this year of commemoration. Everyone should be able to form an informed opinion on the historical reality of Napoleon Bonaparte, his reign and his influence still today in our lives. The numerous debates, works and exhibitions planned for this occasion will be the occasion, we hope, to initiate a true reflection on this character whose myth sometimes crushes the necessary nuance.

The Napoleonic soldiers: a badly shod army

"Speed, speed, speed". These words of Napoleon Bonaparte could succinctly summarize the essence of his strategic genius. The Napoleonic army moved twice as fast as its adversaries. An asset as much as a feat, both supported by an accessory showing itself (almost) always failing: the soldiers' shoes.

Doubtless no campaign was exhausting like the Napoleonic campaigns. That a good physical condition is essential to make a good soldier, no one will doubt it, but more than for any other, the conscripts of the Napoleonic wars had to have an iron health. Probably, no one imagined the harshness and endurance required that soldiers would have to display to face the forced marches on often bad and chaotic terrain.

Conscription then concerned young people aged 20 to 25, in good health naturally. Drawn by lot, the conscripts designated by Fortune – whose good intentions can legitimately be questioned – had to be trained quickly to integrate regiments made up of young and old experienced soldiers. At the cost of intensive and severe military training, it took three months of service to make a recruit into an effective infantryman. However, the very first teaching provided often consisted in differentiating his right foot from his left foot, a rudimentary exercise but essential for the good soldier to walk correctly in step. For these young people, mostly uneducated and more versed in the art of working the land than moving around it in an orderly and synchronous manner, the instructors found a trick that put at the center of the future soldier’s life an accessory that would focus their attention steadily until they return, perhaps one day, to civilian life: the shoes. In the left shoe (or the hoof for those who were not yet perfectly equipped) we placed straw while the right shoe was stuffed with hay. Thus, the soldier went at a walk without being mistaken at the chanted cry of his superior “Straw – Hay!” Straw – Hay! “. The attested anecdote has something to smile about if the problem of shoes in the Napoleonic armies had not become a permanent concern for the General Staff.

The Napoleonic marches

The Napoleonic campaigns to be dazzling must be led by enduring soldiers, without injury and therefore well equipped. Because the steps are terribly long. Linking one city to another, one battlefield to another, often involves traveling tens of kilometers a day in a very short time at a sustained pace. The feat of the troops of General Friant (1758 – 1829) compelled admiration in this sense when his troops rallied the battlefield of Austerlitz by covering more than one hundred kilometers in 44 hours. On average, the troops traveled 50 kilometers daily in often difficult conditions (terrain, climate). We therefore understand the capital importance for soldiers to be well shod.

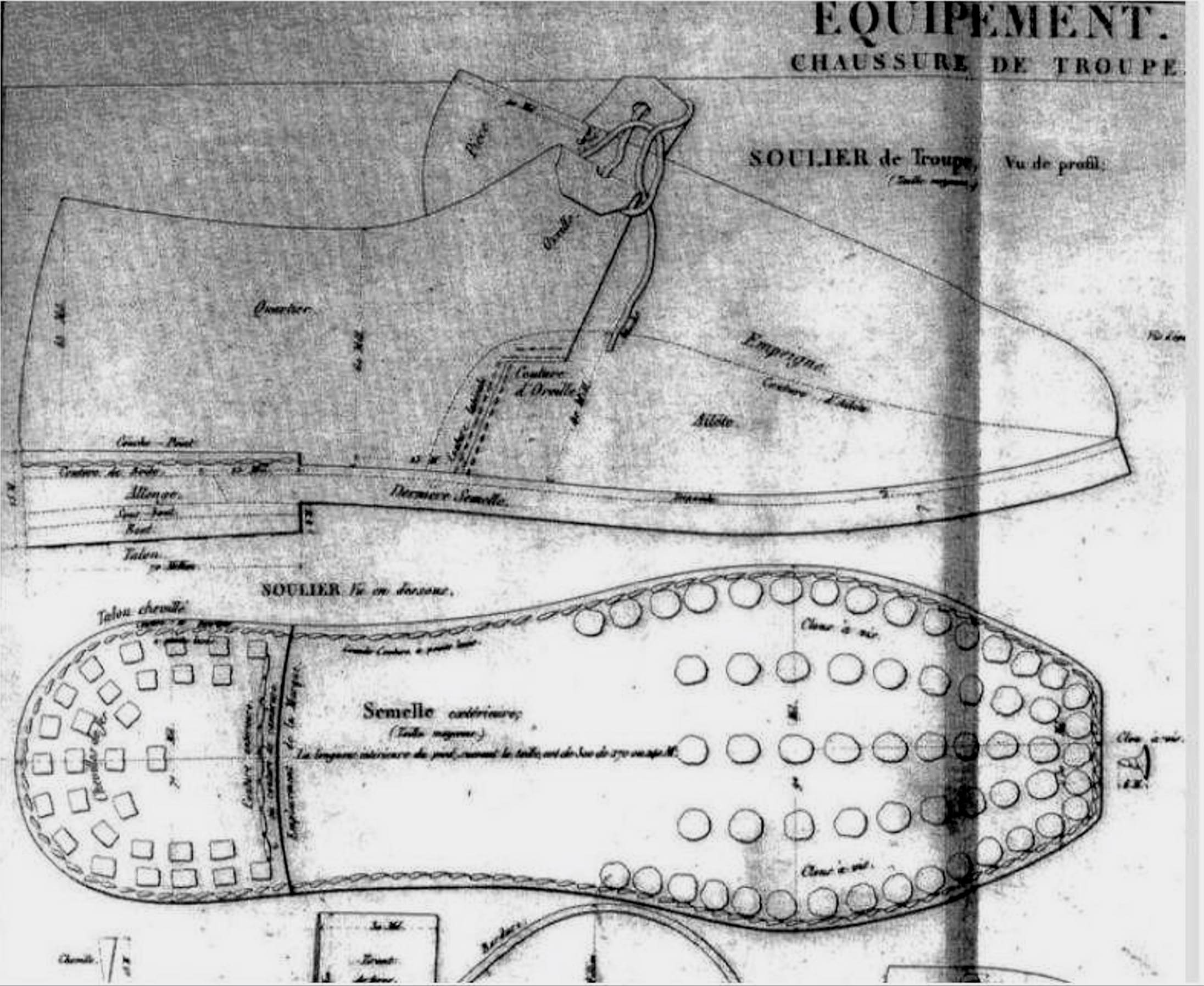

The shoes distributed by the Army were made of turned cowhide and weighed 611 grams (only, one might add). They were of three sizes ranging from small (between 20 and 23 cm) to large (over 27 cm) through a medium size (between 23 and 27 cm). The last sole was in tanned cowhide leather then reinforced with shoemaker’s nails: there were between 36 and 40 depending on the size. The soldier tied them firmly with a leather lace passing through two holes without eyelets; wear was to come to an end very quickly. Like almost all shoes from this era, the toe was square. A peculiarity all the same specific to the military shoe: there was neither right nor left foot. The two perfectly identical shoes were shaped by the foot of their wearer according to the grueling steps he took. Thus, each new recruit was given a uniform, a weapon and of course a pair of shoes normally designed to travel a thousand kilometers.

But the latter were worn out so quickly that numerous testimonies report that at the end of the fighting, the soldiers hastened to remove the shoes of the dead when they did not make their own shoes with the means at hand. During the Spanish Civil War, spare shoes did not arrive, the soldiers became shoemakers in addition to their usual duties. In his Briefs , David Victor Belly de Bussy (1768 – 1848) reports that men made boots for themselves by rolling cowhide around each leg and foot, taking care to leave the animal’s hair out.

Thus, despite the importance that Napoleon Bonaparte always attached to the good equipment of his troops, the stewardship took under the Empire such an extent that the financiers struggling to win military contracts had no qualms about providing poor quality equipment. for the bulk of the troops. Not to mention the problems associated with supplies, soldiers’ shoes were a constant concern and a recurring subject in Napoleon’s correspondence.

The unscrupulous suppliers of the Napoleonic army

The contracts signed with the army were juicy for those who had the means to pay the advances and to come to an understanding in unofficial politics. Corruption and the friendships of a close circle of power were absolutely necessary for anyone aspiring to do business.

For the Italian campaign, it was the Coulon brothers, friends of Bourienne (1769 – 1834) who won the market for soldiers’ shoes, but their bankruptcy put an end to this contract. Before the Battle of Marengo, a treaty was signed with Étienne Perrier and his counterpart Louis Cerf, both shoemaker and bootmaker. These two Parisian artisans were responsible for supplying Hungarian-style shoes and boots to the Army corps. But it was undoubtedly Arman-Jean-François Seguin (1767 – 1835) who won the biggest contract. This chemist had succeeded in developing a rapid tanning process that required only three weeks instead of the traditional six months. Naturally, this innovation attracted the attention of the State, which granted Seguin the market for “all the tanned, wrought and honed leathers necessary for the footwear and the equipment of all the troops on foot and on horseback” for a duration of 9 years from year VI (1796).

These markets with insubstantial economic benefits were not, however, inspected as one might expect from a state order. The financiers therefore made a point of reducing the quality of the products in order to make more profit. The case of the cardboard shoes seems to start off as a joke, but it is not.

For the Russian campaign, the soldiers of the Grand Army were given faux leather shoes with cardboard soles. What would have been an annoyance in Spain turned into a frozen nightmare in Eastern Europe. Gabriel-Julien Ouvrard (1770 – 1846) one of the most important financiers of the time – a character that Bonaparte did not like but needed – was suspected of being at the origin of this dishonest and contemptuous delivery. It seems that no proof can yet formally attest to this.

Napoleon Bonaparte's boots

The soldiers were thus the worst shod. But the higher we rose in the military hierarchy, the more we favored the comfort of our feet (among other things). The highest ranks were gaiters and boots, although the quality was not always there. If necessary, the emoluments however made it possible to afford a pair made of good leather.

Napoleon I never distinguished himself on the battlefields or during the campaigns by an inappropriate luxury and naturally his taste went to simplicity. He always favored quality although he was often negligent. His shoemaker Jacques, installed rue Montmartre in Paris, said that Napoleon had the nasty habit of stoking the fire in the bivouacs with the tip of his boot, thus wearing out many pairs which, without this wicked treatment, would have lasted a long time. Bonaparte attached himself a model of high boots to the rider – supple boots with cuffs – in black morocco which he ordered in numerous copies. He wore a current size 40 and paid them 80 francs, which is 20 francs more than the famous black beaver hat (link). A tidy sum for the commoner, but almost too low for an Emperor whose taste for simple things must be recognized – at least.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Napoleon Bonaparte, Chess Player

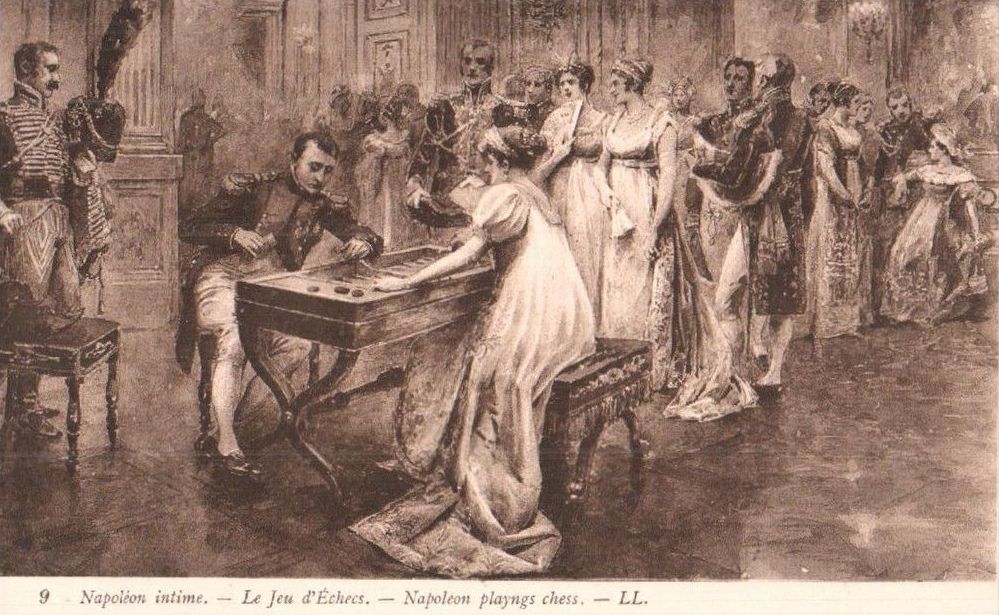

A strategic game par excellence, an elegant symbol of the art of war, chess has been the king of games and the game of kings since the Middle Ages. Napoleon Bonaparte could not remain indifferent to it without, however, and it is surprising, never becoming a brilliant player!

Napoleon, a Bad Sport

If Napoleon Bonaparte often arouses blissful enthusiasm or blind hatred, no one seems to question his strategic genius. Of course, such a talent would seem to find in the peaceful and regular practice of the game of chess the exaltation of this remarkable strategic mind. However, it is not. Napoleon certainly learned the rules of chess when he was a pupil at Brienne; this game was indeed one of the many qualities that good society deemed necessary for a young man. While settling in Paris, the “petit lieutenant” comes to practice “pushing wood” at the Café de la Rotonde or at the very popular Café de la Régence, haunt of the best chess players since the middle of the Eighteenth century.

The revolutionary period, tasting little of the central role accorded to the King’s play, had kept chess in the shade for a few years, reworking its form without changing its substance so that the game espoused the republican cause. But the craze – never extinguished – for the traditional form soon returned and Napoleon was not indifferent to it. Until the young lieutenant had yet dazzled France with the meteoric Italian campaign, no one pay interest to its play on the chessboard. Nonetheless, had he shown the extent of his military genius on Italian soil, it was imagined that he was just as formidable leaning on a gaming table. He was not.

First, let us note that the conception of chess at the turn of the 18th century was very different from today. The strategic theory and the preparation of the attacks were almost nil and the direction of positioning hardly considered. One wanted to shine on the chessboard with the same brilliance as the final assault of a Homeric battle. The games were aggressive and the attacks started quickly without hesitating to sacrifice pieces and pawns for a spectacular checkmate. Nevertheless, circles of amateurs and champions gradually took shape, treaties multiplied and strategy developed. François-André Danican Philidor, nicknamed “the Great” (1726 – 1795), undoubtedly the best player of his time, was also the first to shake up the intuitive and imaginative vision of chess by writing one of the very first treatises on the game.

Probably Napoleon’s way of playing was borrowed from the old and the new manner. But where the future First Consul shone and knew how to use his talent, he lost his advantage on the chessboard. Indeed, on each side of the board, the opponents face the same field and are in possession of the same squad information. In this case, it was impossible for Bonaparte to take advantage of the natural terrain, impossible to bluff on the number of soldiers per contingent. On the chessboard, the two opponents are on equal ground; the strategy and the inventiveness to be deployed are not the same as in real war. Journalist and writer Jean-Claude Kauffmann sums up the game attributed to Napoleon:

The strategist of Austerlitz and Friedland who considered the battlefield a chessboard was a poor chess player. He naively rushed at the opponent and was easily captured, which did not prevent him from brazenly cheating.

Bonaparte was cheating. It’s a well-known fact and not just in chess! We know his impatient and sometimes (often?) difficult character, it is quite easy to imagine him as a bad player. Perhaps he would have been better – at chess anyway – if he had had the opportunity to study the game better. This great reader might not have had the opportunity to look at the treatises newly published. All his life he loved this game without being a top player.

In Egypt, he played with the Comptroller of Army Expenses Jean-Baptiste-Etienne Poussielgue (1764 – 1845) and with Amédée Jaubert (1779 – 1847), member of the Commission for Science and the Arts and translator. In Poland, it was with Murat (1767 – 1815), Bourrienne (1769 – 1834), Berthier (1753 – 1815) or the Duke of Bassano (1763 – 1839) that he played chess. Like a close friend, Bourrienne testifies with sincerity to Bonaparte’s game while Hugues-Bernard Maret, Duke of Bassano goes there with a touch of flattery:

Bonaparte also played chess, but very rarely, and this because he was only a third force and he did not like to be beaten at this game. He liked to play with me because, although a little stronger than him, I was not strong enough to win him always. As soon as a game was his he would quit the game to rest on his laurels.

Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Mémoires

The Emperor did not skillfully start a game of chess. From the start, he often lost pieces and pawns, disadvantages his opponents dared not take advantage of. It wasn’t until the middle of the game that the right inspiration came. The melee of the pieces illuminated his intelligence, he saw beyond three to four moves and implemented beautiful and learned combinations.

Hugues-Bernard Maret, Duke of Bassano

Probably the Duke will have seen the Emperor’s game on a good day … Unless he was dazzled by the pomp more than the game! Because Napoleon Bonaparte was not the type, one would have suspected, to easily accept defeat. In addition, he was impatient, stamped his foot or drummed on the table when he judged his opponent too slow, which did not fail to disturb the arrangement of the pieces on the board … Whether his opponent was human or mechanical, his attitude was the same. A certainty acquired during this famous episode that we never tire of telling.

In July 1809 at Schönbrün Palace in Vienna, a historic chess game was about to take place. Setting up the chessboard and one of the two opponents is laborious; and for good reason: it is about installing an automaton. Imagined and manufactured by Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734 – 1804), this mechanical “Turk” has already played games with some of the world’s greats, including Catherine the Great (1729 – 1796) or even Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790) while the automaton was at the Café de la Régence in Paris in 1783.

In 1809 however, the learned machine no longer belonged to the baron but to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel (1772 – 1838) but still aroused enthusiasm (as well as suspicion, a very natural feeling which would later be legitimized). Napoleon Bonaparte accepts the confrontation with the automaton. The game was chaotic because the automaton seemed perfectly capable of recognizing a cheater when it saw one! So the Turk would put a pawn or a piece in its place as soon as his opponent tried to cheat. A nasty twist that Bonaparte had no qualms about facing the machine. But, the annoyed automaton systematically swept the chessboard with his arm after three fraudulent attempts which, of course, did not fail to happen with the Emperor. The Mechanical Turk thus defeated Napoleon I by disqualification.

In 1834, the deception was exposed. The automaton was endowed with no mechanical intelligence. A set of mirrors and articulated arms allowed a small player to crawl under the automaton and the board and play brilliantly against all the prestigious opponents he faced. Either way, it must nevertheless be recognized that this (or these?) player, as anonymous as he was, was one of the best chess players of the time!

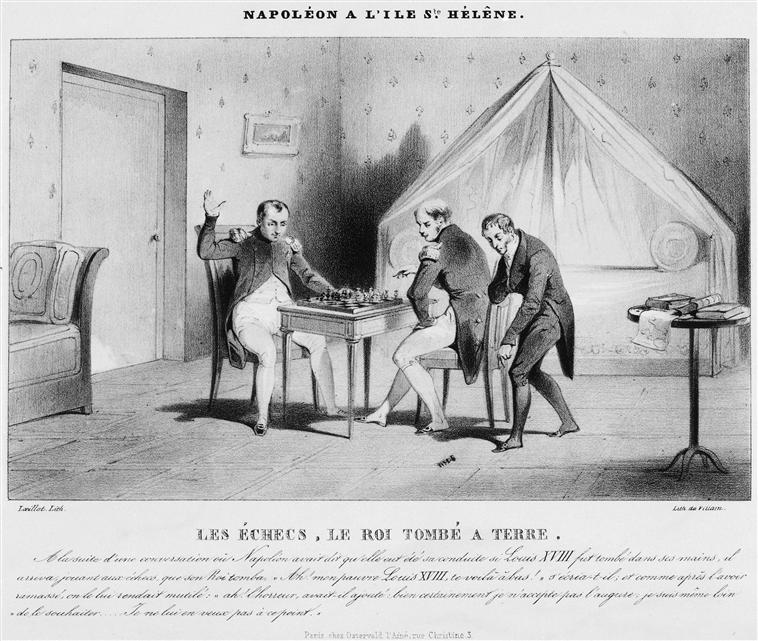

Napoleon at Saint Helena

In 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled to Saint Helena, an island as remote from Europe as the temper of the fallen Emperor. Bonaparte’s unrestrained and permanent activity contrasted with the imperturbability of this isolated rock, one may almost believe that by dint of work Napoleon would be able to make it move. Obviously, one tried to recreate a refined environment, however, the Empereur never fear the Spartan life. Days were often studious but almost every day Napoleon loved to play chess. The 19th-century grandiloquence of the gaming journal, La Palamède, reflects Napoleon’s still strong taste for the chessboard:

If the game of chess had not already attained a high nobility, it would be ennobled by giving a few moments of happy entertainment to the greatest of prisoners and exiles.

La Palamède, 1836

A poetic assertion quickly disheartened by Las Cases :

He was infinitely weak at chess.

It’s a safe bet that Napoleon did not win many games! Especially since Madame de Montholon, who attended many parties during the exile, added that:

Touch-move rule, but it was only for his opponent. For him [Napoleon] it was different and he always had a good reason why it didn’t matter, if anyone notices it, he would laugh.

At least the island air seemed to have softened his bad sport character (in chess at least)!

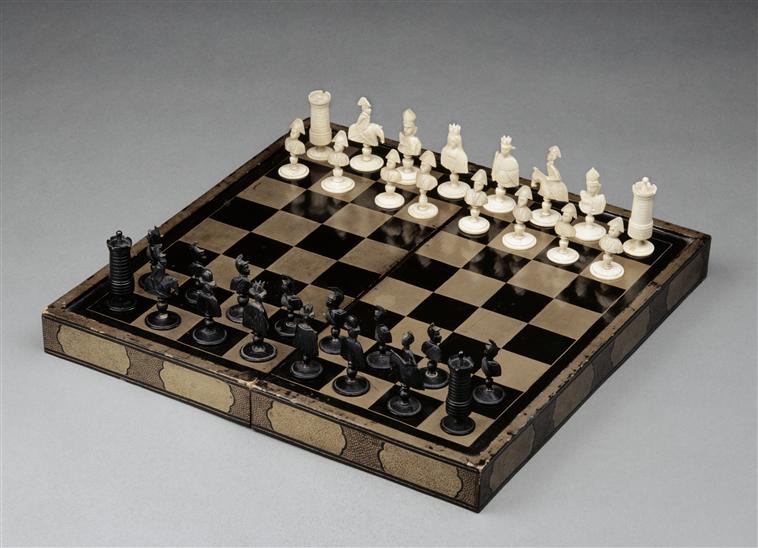

Upon his hasty departure from France, we know that a chess board was carried in the luggage. Nevertheless, Napoleon Bonaparte had at his disposal during his stay at least two Chinese chessboards, one of which was offered to him by… an Englishman.

On July 4, 1817, boxes from China destined for Bonaparte arrived at Saint Helena. In one, a beautiful chessboard and its ivory and cinnabar pieces was the gift to the Emperor from John Elphinstone. The man was then head of the Canton counter for the East India Company and with this elegant gift expressed his gratitude to Napoleon. The latter had indeed saved the life of Lord Elphinstone’s brother during the Belgian campaign in 1815 by demanding that this Scottish aristocrat seriously injured and taken prisoner be treated. The zealous gratitude expressed by the Lord pushed the detail so far as to stamp all the pieces of the game with the imperial monogram. A detail which flattered the emperor but which annoyed even more (because he was always on edge) his jailer Hudson Lowe who accepted reluctantly and after several days, to transmit his present to the illustrious French prisoner.

This gesture of Lord Elphinstone impressed Napoleon more than the game itself, the pieces of which were impressive. The tower in particular was a huge elephant which aroused Bonaparte’s amusement: « I should need a crane to move this tower! » (La Palamède, 1839).

Some pieces of the various chess games he owned were distributed to his companions in exile during the New Year’s Eve. It seems that Marshal Bertrand received a few in January 1817 without it being possible to say with certainty which game it was. Today a set and a few pieces are kept in French museums and in private hands, and sometimes pieces resurface from the past at auctions. Very tenuous memories of the life, character and faults of Napoleon Bonaparte, a fine strategist on the ground but an inveterate cheater on the chessboard!

Napoleonic Wars casualties

Enthusiastic or detractor, there are many who engage in a war of numbers to acclaim or denounce Bonaparte's military operations and their cost in terms of human lives. What is it really?

Although it is difficult to obtain an exact figure, many historical studies are today consensus and allow not only to better understand the Napoleonic history but also to place it in relation to other great wars which marked France and the European continent. We will also appreciate the quality of the long, patient and referenced work of emeritus historians in the face of the epileptic and vociferous agitation of Internet users who are too happy to be freed from any academic commitment to shout a story rewritten by their care, a story whose primary quality is to travel light; in fact, these individuals rarely encumber themselves with serious bibliographic sources. That being said, it’s okay (but not always, as everyone sees on a daily basis) to use the numbers with caution. Chateaubriand accused Napoleon of having killed more than five million French people in eleven years of reign. We know the literary value of Chateaubriand’s writings, we can no longer ignore after reading such an assertion the little importance he made of learning mathematics. Because indeed, figures can say anything and everything depending on whether or not the details are given. How did Chateaubriand arrive at this figure? Impossible to say. Was he a sharp critic of Bonaparte? Did he have any complaints against him? This is no longer to prove. Can we consider as fair and objective the figures put forward without argument by a man who resented the one he accused? Maybe not. This is why the work of historians is once again capital and essential to consider calmly and as objectively as possible such a burning subject.

The death toll attributed to Napoleon’s military deployments spanned fifteen years in several countries. To suspiciously attribute several million deaths to Bonaparte is often an assumed or even claimed approximation, peremptory affirmations are always more comfortable than the complicated meanders of nuance and study. Of course, it is not a question of being naive: the Napoleonic campaigns were not walks in the park and, over fifteen years, the human losses, whatever the camp which one chooses, are considerable. But are they more so than other conflicts before (the Thirty Years War) or after (the First World War)? The response of historians tends to be negative.

Calculating French losses: laborious work

Before considering the figures put forward by historians, let us recall that before the present day, human losses were not or little counted, leaving room for partisan assumptions that were often excessively high or excessively low. Jacques Houdaille (1924 – 2007) – teacher at several American universities and director of research at the National Institute of Demographic Studies (1970-1988) – used the army personnel registers to assess Land army losses under the First Empire. His studies of historical demography are today considered the most reliable by historians and scholars of Napoleonic history. From the start of his study, he drew attention to:

A confusion, difficult to avoid, between soldiers who died in combat and soldiers who died or disappeared under the Empire [which] allowed all the more fanciful assertions since, even for the losses of the French army, it was difficult to distinguish the French born in France, within its borders of 1815, Belgians, Italians, Rhenish and Dutch born in the annexed departments between 1792 and 1811.

This gives a little insight into the difficulty, knowledge and mastery of research protocols and historical tools as well as the patience required to undertake such a study. The figure put forward by Chateaubriand quickly appears inconsistent compared to those collected by researchers. Because if 2,432,335 French were called to military service from 1799 to 1815, two million were actually conscripted (Chateaubriand’s five million are largely excessive). For France alone and based on the work of Jacques Houdaille and those of other historians, we manage to establish a high (one million dead) and low (400,000 dead) range of human losses over the cited previous period; and if the estimate is still difficult, as Thierry Lentz, the director of the Fondation Napoléon, rightly points out, it can reasonably be argued that the average range – or around 700,000 French deaths – is the closest to the truth.

European losses and losses during the great battles

This fifteen years of history obviously did not affect only the French. The European toll is also high and the average estimate tends around more or less two million dead, including the human losses of Russia (500,000 men), Prussia and Austria (500,000 men), the Poles and Italians (200,000 men), the Spaniards and Portuguese (700,000 men) and the British (300,000 men). *

The reports are further refined thanks to the patient studies of the battles led by Danielle and Bernard Quintin ** using the method of Jacques Houdaille. Thus for the Battle of Austerlitz (December 1805), there were 1,538 dead in the French camp for 72,500 combatants, or 2.12% of the troops. In Eylau (February 1807) 2711 died and 44 presumed dead, i.e. a 5% loss, and at Friedland (June 1807) 1,849 men were killed, 68 presumed dead and 341 missing.

Of course, the loss of life is colossal and always too high, whatever the conflict. But are they more so than other wars that have ravaged Europe? Obviously no.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648) caused nearly two million deaths among combatants and even more among civilians. There are at least five million victims for a total population of fifteen to twenty million inhabitants in the Holy Roman Empire. The First World War caused 18.6 million deaths in four years, including soldiers and civilians. Some will be offended to see us compare conflicts and their losses with regard to the demographics of each era or to the weapon technologies employed. But in this case, how do you support the idea that Napoleon Bonaparte was a power-thirsty with no regard for the lives of his soldiers? An assertion works against a referent, and in either case (in comparison or without comparison) the argument does not hold. Judging Bonaparte’s action against what our time considers the right way to act as head of the army is also unreasonable. The beginning of the 19th century is a far cry from our post WWII era. However, let us insist on this point: Napoleon Bonaparte is not a holy personage or an incarnate demon. He was an ambivalent, opportunistic and ambitious personality in a time of turmoil. Let us also remember that the Napoleonic wars are largely (not all, we insist: in large part) the continuation of the wars of the French Revolution which then responded to the attacks of the united European monarchies.

Napoleon Bonaparte cannot be credited with the invention of war nor with the complete loss of life in the conflicts of the first fifteen years of the 19th century. Although an emeritus strategist, he was recognized during his lifetime – and testimonies abounded in this direction after his death – as a man close to his soldiers, the latter appreciated and recognized his experience in the field. A quality that many military leaders will not have during the First World War, a hundred years later.

As often, this historical figure crystallizes blind partisanship or stubborn hatred, the two having in common being simplistic. As History is nuanced, so are the characters who make it up. Only the work of historians can scientifically shed light on the areas of our history; to better understand it, we must rid it of its preconceived ideas and accept to question our certainties in the light of the most serious and recent research.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

*Chiffres issus de l’étude de Alexander Mikaberidze, avocat et historien considéré comme un des meilleurs spécialistes étrangers du Premier Empire.

**Auteurs d’ouvrages de fond sur le Premier Empire, ils reçurent en 2007 le Prix spécial du Jury de la Fondation Napoléon pour l’ensemble de leur œuvre.

Joseph Bonaparte in America

First of the Bonaparte siblings, Joseph (1768 - 1844) was also the closest to Napoleon. The eldest of the family had a taste for the arts more than for power, and it is undoubtedly for this quality that the United States gave him the best years of his life.

The Departure

Joseph Bonaparte did not have time to take advantage of his privilege as a big brother for long. The young Napoleon, born a year after him, would turn upside down his life and that of his family. Although these two were bound together all their lives by a deep brotherly love, the younger often bullied his elder. The latter always tolerated wickedness with a patience that should command respect. The two were a pair, however, one climbing the ladder of power while the other remaining in the shadows amassed fortune and distinction, serving his brother’s ambition more out of loyalty than taste. Although he certainly had a taste for diplomacy, a quality one would imagine to be necessary when it came to living and working in the circle closest to Napoleon. Joseph, who was determined not to anger anyone, certainly had every opportunity to perfect this art during the reign of his brother. In turn, he was ambassador, senator, king of Naples, then leaving Italy for Madrid, he became king of Spain, general lieutenant of the kingdom in 1814 and finally president of the Council of Ministers during the Hundred Days. The fall of Napoleon was not, however, quite his. With his voluntary exile in America, Joseph was going to begin the best years of his life, more than twenty years of daily savoring what he liked the most, reading, receiving and living comfortably surrounded by art and friendly people.

Overnight between July 24 to 25, Joseph left the French coast, leaving behind his brother, whom he would never see again. He embarked for New York on a discreet brig with his aide-de-camp, his cook and his interpreter James Carret who left to posterity some notes on their Atlantic crossing, notes which set the tone for the comfortable future that will be offered to Joseph in the New World. The trip was pleasant and punctuated, according to James Caret, with the poetic enthusiasm of Joseph, who brilliantly recited French as well as Italian poetry, declaiming entire passages from Tasse, Racine or Corneille without any oversight. Joseph’s memory seemed to be as powerful as his voice, certainly intoxicated by the vastness of the ocean, chanted as if he wanted to be heard from both the old and the new continent.

Arrival in New-York

He first set foot in America on August 20, 1815. Newly arrived in New York, Joseph’s new life, to be pleasant, had to be discreet. The fall of the Emperor and his exile had ushered in a new era in Europe, and times did not spare Bonaparte’s former relatives and supporters. Joseph was perfectly aware that he had to keep a low profile and adopted for his peace of mind the name of Comte de Survilliers. The title was not usurped as it was that of a small property that Joseph owned near Mortefontaine, his French beloved estate. Throughout his stay, even after he was discovered as the brother of the fallen Emperor, he retained this name by which he always presented himself in America.

In New York, he introduced himself to Mayor Jacob Radcliffe, who urged him to come to Washington and make known his kind regards to President James Madison (1751 – 1836). For Joseph in fact had no political inclinations in America, quite the contrary! But as was to be expected, the reception was reserved. On his way to Washington, a messenger came to meet the elder Bonaparte informing him that the president could not receive but that he wanted to assure Joseph that he could remain in the United States as long as he pleased if he remained discreet. It was obvious to Joseph and even rather a wish than a condition. So he turned back to where he came from.

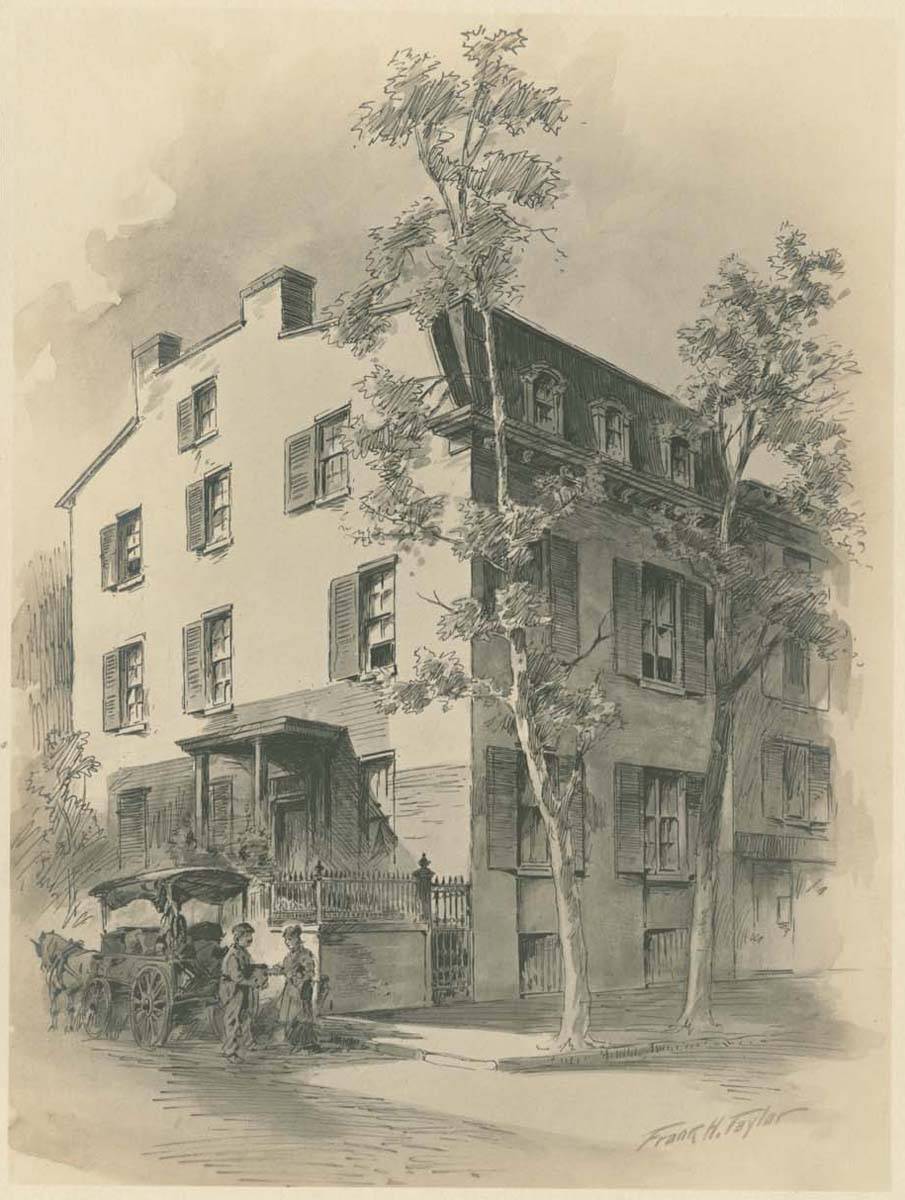

Some time later he left New York (where he was unwillingly recognized as the former King of Spain) and found a home in Philadelphia, at the corner of Second and Markets Street.

This residence hosted Bonapartist refugees as well as other passing French throughout the stay of the former King of Naples. But one never maked waves, visitors always prefered finding in Joseph’s home the comfort of speaking French language as finding the customs and traditions that made French culture. For Napoleon’s brother, the residence was ideally located about fifty kilometers from the land he had just acquired in Bordentown (New Jersey) and which he was busy developing. The house would soon become a benchmark of good taste and French art de vivre because Point Breeze estate, owned by the Count of Survilliers, was for Joseph the work in which he invested much of his fortune but even more himself.

Conveniently located along the Delaware River, in a beautiful landscape, Point Breeze estate required four years of development during which Joseph spared no effort. Supervising the work himself, it was not uncommon for him to show up dusty and in mud-covered clothes, far away from the distinction befitting the duties he had once held. The park was cleaned, fitted out with walks, gardens and flowerbeds. Inside, paintings, bronzes, marble busts, statues and tapestries amazed visitors who were astonished to discover the rooms and lounges, one more elegant than the other. Frances Wright, an English visitor, gave a precise description of reception rooms in the house. Each was furnished with superb mahogany pieces in the finest French style that we now call Consulate and Empire (link). The billiard room was probably the one that Joseph liked most because he spent a lot of time there with his guests. Adorned with white curtains edged in green, the carpets on the floor were white and a very beautiful red. On the walls we admired paintings by Rubens and Vernet, the palettes of which were not to clash with the colors of the room.

Adjacent to the billiard room, the Great Hall was the privileged place for large receptions. The most beautiful pieces of furniture were there, the walls hung with the same blue fabric that covered the armchairs and benches. In the center of this sumptuous room, two spectacular tables with marble tops – gray for one and black for the other – presented a superb collection of bronzes. It seems that a white marble fireplace donated by Cardinal Fesch (1763 – 1839) was also installed in this elegant room. On the floor was a Goblin rug so large that it covered almost the entire surface of the room. And everywhere masterpieces, objects and works of art of the highest quality adorned walls and furniture with a taste that made a visitor tell out loud what many were secretly thinking, namely that Point Breeze was arguably the most beautiful estate of America.

Patron of the Arts

Joseph won unanimous support everywhere. This refined man charmed with his wit, his discretion and his liberality. Certainly because our Bonaparte never failed to open the doors of his home to passing visitors, to curious people, to neighbors and even to artists eager to admire or copy the superb masterpieces which made all the salt of Point Breeze. His desire to promote French and European art through his collection did not stop there. Anxious to show to many people as possible the paintings of the most famous masters in his collection, between 1822 and 1829 he loaned several paintings to the annual exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts in Pennsylvania. His Bonaparte crossing the Grand Saint Bernard signed by the hand of the famous Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825) was presented each year and it was considered by the painter himself as “a great honor”. But Joseph Bonaparte, as a great connoisseur and patron that he was, knew the importance of not underestimating the unknown artists who would perhaps make the famous names of tomorrow. Thus, he welcomed painters artists, both professional and amateur, but one anecdote conveys better than words Joseph’s still keen interest in art rather than ostentation. One day when the young apprentice George Robert Bonfield (1805 – 1898) was sent to Point Breeze for some job, the young man took advantage of a few stolen moments to copy down into a small notebook – which he kept near him – details of a Shipwreck of Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714 – 1789). Joseph passing by surprised the apprentice who had great difficulty in hiding his drawing in time; Joseph then asked to see the notebook and George sheepishly handed it to him. He later rejoiced at this awkwardness because Bonaparte, impressed by the young man’s talent, allowed and encouraged him to draw whatever he wanted in the house! Bonfield made a career and later became an important cultural figure in Pennsylvania.

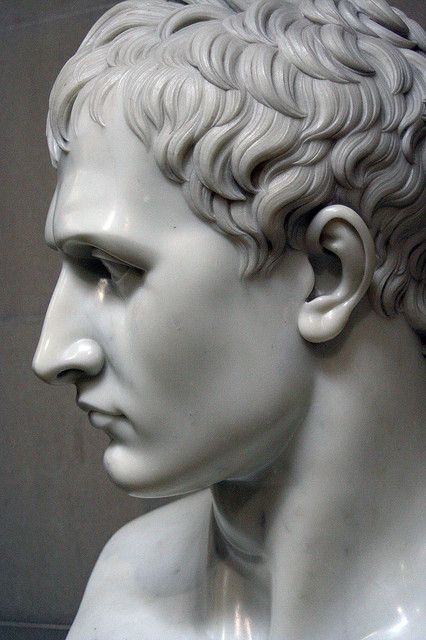

You have to imagine what the possibility of drawing and reproducing the masterpieces from the Point Breeze collection meant for our young painter. Because if David’s painting was certainly one of the most spectacular, one could also admire works by the hand of Correggio (1489 – 1534), Titian (1490 – 1576), Pierre Paul Rubens (1577 – 1640) or Antoine van Dyck (1599 -1641), of Vernet and David Teniers the Younger (1610 – 1690) as well as Paulus Potter (1625 – 1654), Charles-Joseph Natoire (1700 – 1770), Jean-Baptiste Wicar (1762 – 1834) or François Gérard (1770 – 1837). Without counting the tapestries of the Gobelins, the bronzes and sculptors of the greatest names such as Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822) whose Joseph possessed a bust of Madame Mère (Letizia Bonaparte), a bust of Pauline Borghese and one of Napoleon, of which several visitors admitted that at first glance it was difficult to say whether it was a bust of the Emperor or of his brother as the resemblance between the two was striking!

Point Breeze therefore appeared, in fact, as an emblem of French taste in general but more broadly as the refined taste of the Old Continent, bearing the memory of the former lives of Napoleon’s elder brother whose artworks, it must be said, were not always added to his personal collection in a very legitimate way… But times were different and so were mentalities!

In America, he was not held against him and we constantly marveled at his collection and his library (then the largest in the United States since that of Congress had only 6,500 volumes while that of Joseph had more than 8,000 !) as well as on jewels and gems whose provenance was still questionable… Whatever! We weren’t going to take offense at this affable and courteous man who gave work to all (it was said that in Bordentown there were no poor as long as Joseph Bonaparte lived there). Every Sunday, the doors of the residence were opened wider and opened the vast park along the Delaware River to residents of the neighborhood who did not deny themselves their pleasure! The delights of the gardens in summer were matched only by the frozen lake in winter. In what is now known as Bonaparte’s Pond, one skated happily on the thick ice while Joseph rolled apples on it, which the skaters enthusiastically chased.

The inhabitants held the Comte de Survilliers in high esteem and never missed the opportunity to greet him when he passed by on horseback – an activity to which he was very attached – and, for his birthday, a brass band was sent to him from the locals. We couldn’t ask for a better neighborhood in Bordentown. Bonaparte did not like discord or aggressive confrontations, always preferring arrangement and negotiation. One example: when the railroad came to pass through his Point Breeze lands, he did not even consider a lawsuit that promised to be as long as it was uncertain. He settled out of court an inconvenience that became a source of profit: in exchange for the train to pass through his property, Joseph obtained a thousand shares in the Baltimore railway company. All his life, the elder brother of the Bonaparte family had shown remarkable intelligence in business, thus accumulating a colossal wealth which allowed him to live in more than luxurious comfort without having to worry about a thing. Although the phrase is exaggerated, it has been said many times that Joseph Bonaparte was the richest man in the United States, which already says a lot about what this character showed of himself to other people.

Taste of America

Joseph had arrived in New York without his wife Julie Clary (1771 – 1845) who never joined him there. In fragile health, she preferred to settle in Switzerland, in Brussels and then in Florence, where Joseph would find her at the end of their life. If American society was full of praise for the former King of Spain, we can at least say that it was careless about the very personal notion that the man had of marital fidelity! Annette Savage (1800 – 1865), whose Quaker family claimed to be descended from Princess Pocahontas, was his first mistress in the New World. Two children were born from this union: Caroline Charlotte in 1819 and Pauline Josèphe in 1822. He also fell in love with Émilie Hémart, wife of one of his lawyers (who was clearly not destined to become a divorce professional). Émilie gave birth to Félix Joseph, born in 1825. Either way, Joseph never neglected his children and always made sure that they lacked nothing.

It is easy to understand from studying his American life why Joseph Bonaparte said he was spending the best years of his life at Point Breeze. To Frances Wright, our English visitor, who pointed out to him that he seemed very happy to be busy embellishing his park and his house, he gave her a colorful response. As he plucked a small wild flower, he compared this tiny beauty to the pleasures of privacy while the showy blossoms in the flowerbed reminded him of ambition and power that he felt presented better from afar than near. He will always remember this American happiness and his friends there. It was moreover as a friend that he was gradually considered, until he was received at the White House by Andrew Jackson (1767 – 1845) not as a political refugee but as a friend of America. It was also in this same spirit that he was admitted in April 1823 to the American Philosophical Society founded by Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790) in 1743.

Yet he lived through discouraging and painful times there. The fire which ravaged his home on July 4, 1820 was dramatic without however destroying it completely, reassured that it was by the help and the kindness of the inhabitants of Bordentown, what he testifies in a letter to the mayor, William Snowden:

You have shown me so kind an interest since my arrival in this country, and especially since the incident of the 4th of this month, that I am sure you will be willing to say to your fellow citizens how greatly I am touched by what they did for me on that occasion. I being absent myself from home, they hastened, of their own accord and at the first alarm, to overcome the conflagration ; and, when it became evident that this could not be done, they directed their efforts to save as much as possible of what had not been already destroyed. The furniture, the statues, the pictures, silver, jewels, linen and books, in fact everything that could be brought out, were placed with the most scrupulous care under charge of my servants. Indeed, all through the night, as well as upon the following day, boxes and trays were brought to me which contained articles of the greatest value. This proves to me how clearly the inhabitants of Bordentown appreciate the interest that I have always taken in them.

The Count of Survilliers rebuilt a second house on the same land. It was in this home that he learned of his brother’s death in 1821 and his mother’s death in 1836, two ordeals for Joseph. For if he didn’t show it, didn’t talk about politics, and pretended not to care (at least for a while), the loss of his younger brother and his mother were undoubtedly painful trials. After a brief return to Europe from 1832 to 1835, he returned to Point Breeze where he lived for another five years until 1839. The death of his own daughter Charlotte in 1839 followed shortly after by that of his dear uncle Joseph Fesch then (only 5 days later) the death of his sister Caroline decided him to return to Europe for good. He eventually joined his wife Julie in Florence in 1840 and lived there for the last few years suffering regularly from stroke before falling into a coma on July 27, 1844 and dying the following day.

When he left the United States for good, he left nothing but good memories. Several of his friends received wonderful gifts from him from his superb collection of artworks and art objects. A large part of these gifts are now exhibited in American museums and one even find in the White House, at the entrance of the Red Room, a mahogany console that Jacky Kennedy particularly appreciated and which was first the property of Joseph Bonaparte. At auctions, a few objects sometimes reappear, testifying to the pomp and assured taste of Napoleon I’s elder brother. Joseph Bonaparte will never cease to assure himself that he lived, in America and at Point Breeze in particular, his best years. Praising the prosperity and beauty of this country, he undoubtedly appreciated the possibility of being himself at last. Now freed from the obligation to serve his brother’s consuming ambition, America was for him the land of a new life – light, luxurious and comfortable – a much coveted life as a gentleman farmer.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Napoleon at the Table: a Gastronomic Paradox

While Napoleon Bonaparte was not a great lover of gastronomy, he nonetheless was perfectly aware of the importance of the table in the daily practice of politics and diplomacy. He gladly delegated these boring meals to his marshals who saw no penance in it, even pushing the cooking to such a level that French gastronomy radiated everywhere with a brilliance that still shines today.

The Golden Age of French Gastronomy

Without doubt there was a before and an after the Empire in the history of French gastronomy. But where we would expect our Napoleon, legislator of good fare, he is not. Not at all. Worse, if Bonaparte had been able to delegate the need for food to another, there is a good chance that today we had no cutlery to attribute to this character. However, the post-revolutionary context at the turn of the 19th century favored a reorganization of society, we witnessed a rapid and remarkable development of restaurants and caterers. Did the French have more appetite at this time than under the Ancien Régime? Obviously no. But the cooks formerly serving in noble, princely and aristocratic kitchens very quickly had an imperious and ironic need for food. Their employers having partly emigrated and shortened for many, it was necessary to find a living by practicing what one knew best how to do, namely to feed those who did it in the wrong way. For as early as the 19th century, a clumsiness in the handling of stoves was detected in the part of the population, this was also coupled with a spending power which largely excused this incongruous incompetence. Idle cooks therefore hastened to provide hungry gourmets with places where they could find all the comfort of satiety in exchange for a significant reduction in their purses. And a well-proven and perfectly synchronized ballet saw bellies swell as purses dried up. Restaurants were thus born, developing and adapting to all kinds of customers and budgets while at the same time large caterers were established, offering the services of a home restaurant for those who lacked the lavish service of the Ancien Régime. Between 1800 and 1815, the very young restaurants daily supplied the public most in sight ; one gladly goes to Chez Méot, rue de Valois, which will soon become the fashionable Boeuf à la mode or to the Café Véry at the Palais-Royal. Opened in 1808, it was the first fixed-price restaurant in Paris and also considered the best in the city. Balzac evokes it in La Comédie humaine since Lucien de Rubempré has his first Parisian lunch there:

A bottle of Bordeaux wine, oysters from Ostend, a fish, macaroni, fruit … He was pulled from his dreams by the total of the menu which took away the fifty francs with which he thought he was going very far in Paris. This dinner cost a month of its existence in Angoulême.

Restaurants at least and the table more widely are a new luxury that distinguishes – in a different way than with aristocratic particles – those who matter from those who can easily be forget. Bonaparte had the good idea, despite his little taste for these food things, not to neglect the table, using it for his politics and his diplomacy as soon as he found himself in the position to govern or to negotiate. It was Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès (1753 – 1824) and Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754 – 1838) who were notably the most zealous emissaries devoted to this task, Napoleon, now Emperor, had widely encouraged them to do so :

Welcome to your tables all the French and foreign personalities passing through Paris to whom we have to do honor. Have a good table, spend more than your salary, incur debts, I will pay it!

The importance of gastronomy in French diplomacy was already recognized in January and February 1801 when an anecdote occurred during the Lunéville congress. Cambacérès, then Second Consul, learned that the first one had forbidden, during the congress, the mail delivery to be nothing other than dispatches and couriers, effectively preventing the delivery of hens and pâtés. Cambacérès complained to Bonaparte, who had to yield to the urgent necessity:

How do you expect us to make friends if we can’t give fancy food anymore? You yourself know that it is largely through the table that we rule.

This famous argument of the Second Consul was with Talleyrand nothing less than a law. First known as a priest – whose libertine escapades and relative integrity contradict a possible natural inclination towards religious principles – Talleyrand was undoubtedly an outstanding diplomat, perhaps one of the greatest in History, as well as an equally remarkable gourmet. Failing to be assiduous in the religious office, he was always scrupulous in that of his kitchens. Every day he went there, discussed and studied each dish with his brigade, at the head of which he appointed the chef Antonin Carême (1784 – 1833), of whom we will speak later. As he explained to Louis XVIII, Talleyrand to practice his art “needs pots more than written instructions”. And for good reason ! This fine gourmet used the table as a weapon of diplomacy and his French-style service was literally listening to his guests: to each guest was attached a valet who was responsible for pouring the drink, removing the empty glass and serve to the plate the dishes all arranged on the table together and at the same time. Patiently and discreetly, each set back valet listened attentively to his master of one evening’s words and scrupulously reported to Talleyrand the next day everything that had been said at the table the day before.

Nicknamed the Lame Devil, it has been said that “The only master Talleyrand has never betrayed is Brie cheese,” a scathing assertion that depending on your perspective … always holds true.

Talleyrand was a formidable politician and diplomat, very intelligent and incisive, he spared no one. The rivalry which opposed him to Cambacérès also took the way of the table growing the aura of gastronomy in no time thanks to a permanent one-upmanship between the two foodies.

Empire Gastronomy in the Service of Power

Let us quote several talented cooks who put knives and pans in the service of the power: François Claude Guignet, known as Dunant (or Dunand), cook who entered the service of Bonaparte very early and to whom we owe the famous Marengo chicken, tinkered with in the rush after the victory of the same name, in June 1800 in Piedmont. André Viard (1759 – 1834), author of the famous Le Cuisinier impérial, ou l’art de faire la cuisine et la pâtisserie pour toutes les fortunes, a work that will have the flexibility to adapt throughout the tumultuous nineteenth century becoming Le Cuisinier royal, then Le Cuisinier national and again Le Cuisinier impérial… Viard, a discreet but eccentric character, was a genius in his field, in fact attracting the attentions of Cambacérès, who entrusted him several times with the organization of his grandiose meals. But certainly, the name of the most famous of all was not destined to cook feast, it even foreshadowed the opposite. Antonin Carême (1784 – 1833) (Carême meaning Lent in French) was during his lifetime described as “king of chiefs and chief of kings”, the first also to bear this title of “chief”. Initially a pastry chef, the young man drew inspiration from architecture to erect spectacular sweet constructions that were soon recognized as delicious centerpieces. The architectures took on the appearance of temples, ancient ruins and pyramids which did not fail to seduce the service of the First Consul. Carême studied tirelessly and successfully tried classic cooking, allowing him to enter the service of a Talleyrand who challenged him to cook for an entire year, never repeating himself and using only seasonal produce. The challenge successfully met, the fame of Carême was made both in France and abroad.

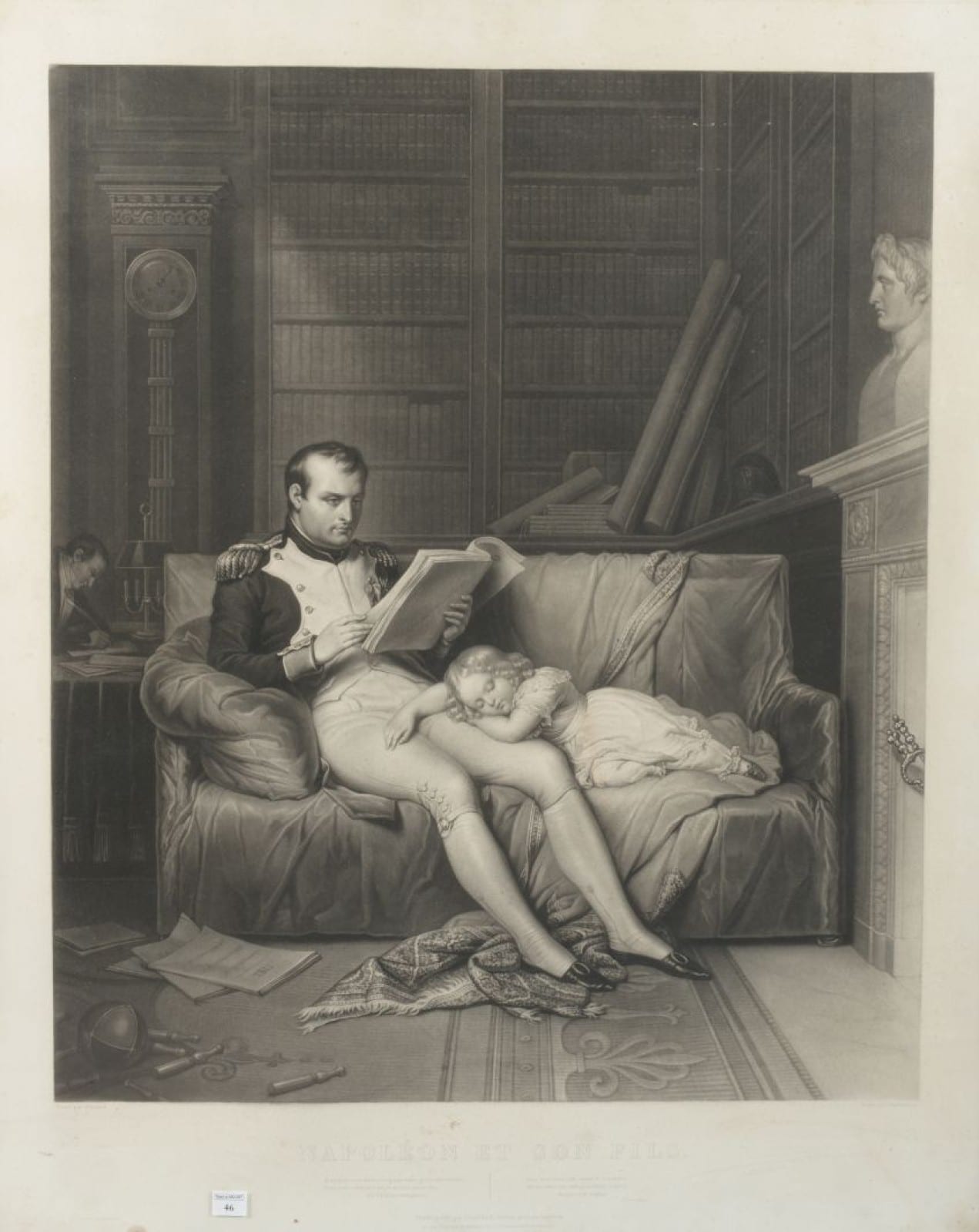

If Napoleon is (almost) perfectly indifferent to culinary pleasures, he is well aware that he is certainly the only one in this disposition. Joséphine, having a sure taste in all things, is therefore in charge of the receptions at Malmaison. This activity will not awaken a sudden and passionate taste for accountancy. As with regard to the layout of her residence, her toilets, her ornaments, her works of art, her garden or even her dog, she spends resolutely and without ever trying to haggle; an eminent quality according to the sellers, an annoying blemish according to her husband.

For wine alone, expenses amounted to around 50,000 francs per year (or around 50,000 cheeses or 2,500 kg of butter). To dazzle the distinguished guests who were sure to parade through the Empress’s favorite residence, nothing was too beautiful or too fancy. The best cooks were therefore begged to constantly strive to develop the most delicate dishes, adding to their recipes a sometimes Creole touch in homage to the hostess. Fruits and vegetables were cooked with exotic spices and flavors, accommodating meats and dishes that sometimes recalled the Emperor’s simple tastes. The meal always opened with a soup of which there were an infinite number of variations: fat, lean, tortoise, princess, Turkish, Italian, etc. Then the dishes followed one another, forcing admiration. Poultry cappuccino with coffee, avocado « féroce », osso-buco with orange-vanilla rubbed shoulders with dishes more to Napoleon’s taste: veal kidneys in a crust, macaroni timbale, polpettes and sweet potato, limoncello babas or, more surprisingly, fricassee of crows. All staged in an elegance never seen before.

Let us note here the talent of the Renards Gourmets who excel at reproducing these delicate dishes of the Empire – Macaroni timpani, Chicken Marengo, Polpettes or Vol-au-vent and many others – in a setting to which the great men of the gastronomy we are talking about would not have been indifferent:

Crystal Saint-Louis or Baccarat glassware is everywhere. It is both on the ceiling and on the table, at the rate of one glass per drink (water, wine, liquor and champagne) when the aristocrats of the 18th century used French service, Russian service – still practice today, namely serving one portion per plate – was preferred at Malmaison.

The cutlery is silver and can be distinguished according to its use: soup, meat, fish and cheese. The fragile vermeil is reserved for desserts. Sèvres porcelain services – of which the famous “Emperor’s private service” is the masterpiece – adorn the tables with delicate painted scenes. Adorned with subjects evoking the Emperor’s campaigns, his conquests, his imperial residences or the great institutions set up under the Empire, this service consisted of 72 pieces, some of which were sometimes offered as gifts by Napoleon himself. In Saint Helena, where he was authorized to take this precious souvenir, he never used it but kept it to offer as New Year’s gifts (link) to those who were dear to him and thus keep alive the memory of his reign.

Others had no other wish than to leave their memory to culinary creations, nothing was more fancy in this first half of the XIXth century. Labeling with his name a famous recipe distinguished the socialites from the common. Chicken à la Duroc, soles à la Dugléré or à la Murat, Matelote à la Kleber, quail fillets à la Talleyrand or timbales of truffles à la Talleyrand (one will note the simple tastes of the Lame Devil) and even the Joséphine chicken and Marie-Louis poularde (because it seems that the empresses are only suitable for poultry). No Napoleon-style meal, and for good reason, the man was an austere eater, perhaps a memory of a childhood when Letizia’s table was neither refined nor expensive.

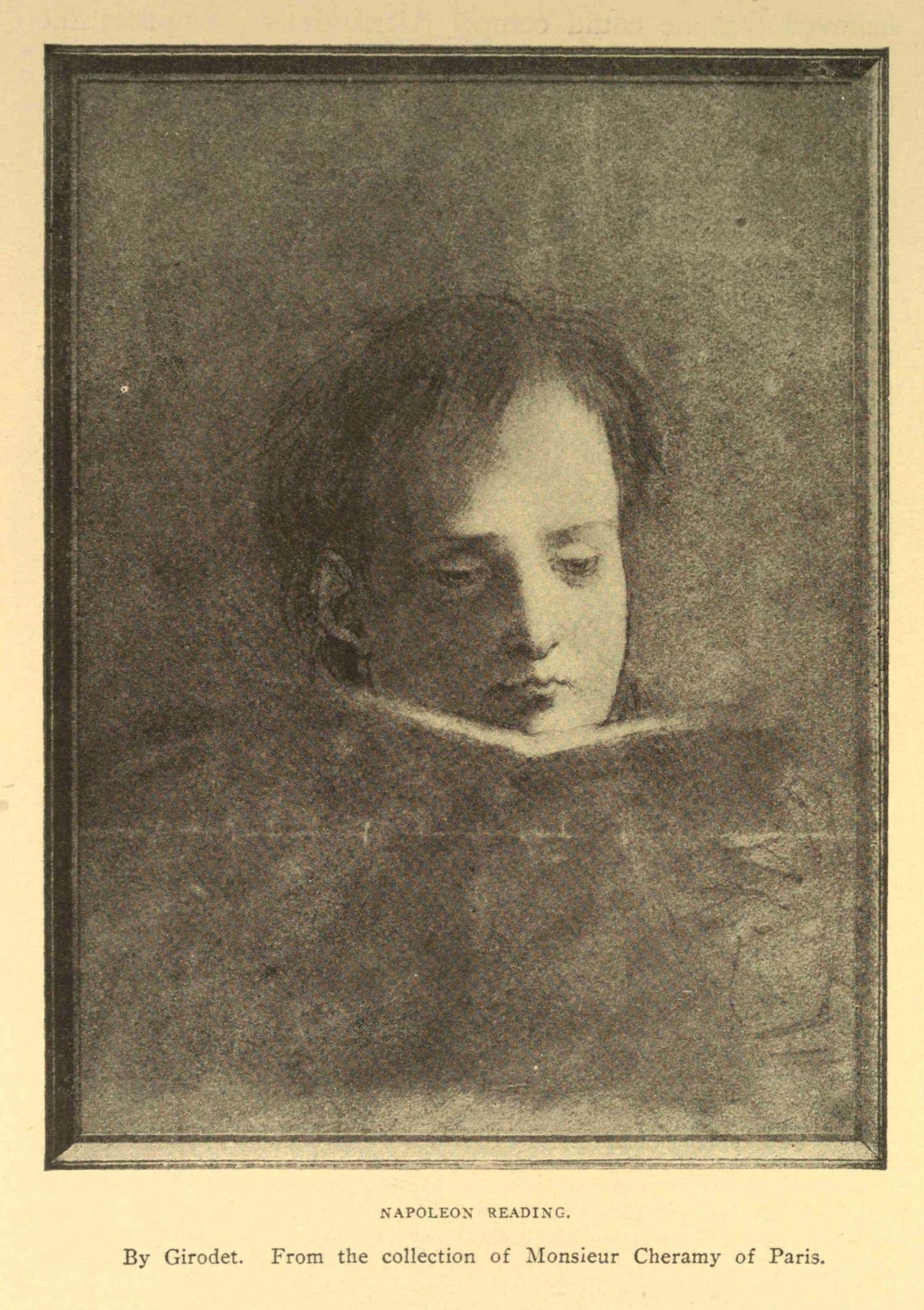

Napoleon's Favorite Dishes

What did the Emperor eat? Let us first specify that he ate quickly: it is said that the First Consul ate in 15 minutes and the Emperor in half an hour on the condition that he was not in campaign, in which case the meal was eaten standing, on horseback or with his soldiers and in a few minutes.

Such rapidity necessarily tolerated a lightness of manners, as evidenced by the magistrate and knight of the Empire Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755 – 1826):

[Napoleon was] irregular in his meals and ate quickly and poorly.

And many of his close friends testify to this habit of eating on the fly on a pedestal table, without a napkin, sometimes with his fingers and wiping himself on his uniform which could hardly endure this ordeal; Napoleon therefore often changed his clothes after his meals. Day or night, he could ask for hot pâtés, poultry or any dish he liked at any time. The Emperor’s service always had to have ready veal kidneys, potatoes, chestnut polenta, or macaroni that Bonaparte particularly liked (so much so that during the Russian campaign, the stewardship bought no less than 250 kilos of this Italian specialty). Napoleon loved coffee and chocolate, which he sometimes consumed excessively when working late at night. Generally speaking, Bonaparte liked only the simplicity of lamb chops, fried eggs, crepinettes or pasta. From the Egyptian countryside he brought back a strong taste for dates and from his Corsica, infusions of orange blossoms. He drank ice-cold water and used it to pour into his Chambertin wine, sometimes a glass of champagne and often a glass of cognac, a liqueur he particularly enjoyed.

Such indifference to gastronomy thus had the merit of not increasing the burden of his exile in Saint Helena. The meals usually consisting of a soup, two dishes of meat, a dish of vegetables and salad had nothing to please or to displease him.

His reign was, however, a remarkable and important period in the history of gastronomy: the appearance of the first restaurants and fine gourmets, the unprecedented recognition of cooks and their literature as well as innovations forced by the continental blockade (think of the development and the industrialization of beet sugar production), military campaigns (Nicolas Appert was the first inventor of glass cans although the patent for tinplate ones was filed by the English) or the success of potatoes which in the 19th century became a common food for all layers of the population.

Although he was the one who re-established the etiquette borrowing directly from that of the Ancien Régime monarchy, Napoleon Bonaparte was certainly not the one who was most enthusiastic about the Grand Vermeil, this service offered by the city of Paris on the occasion of the imperial coronation. Knowing the pomp and ostentatiousness necessary for the recognition of the Empire on the European scene, Napoleon I offered to see this magnificent service, whose spectacular nave was placed next to him, more to the satisfaction of the major figures of the time than for his own. The same was true for the art of the table and the gastronomic subtleties. Leaving the endless meals that bored him to others, he however always enjoyed sharing simple bivouac meals with his soldiers.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Napoleon Bonaparte's Bicorne Hat

A recognizable figure among a thousand, Bonaparte is one of the few people who can be identified by the mere shadow of his hat. Napoleon's cocked hat was the signature of his legend.

The Hat That Made the Legend

As far as the portraits of Napoleon go back, only the imperial crown has supplanted the famous cocked hat. An exception of prestige which, however, only manages to equal in our imagination what this forehead wore the most and the best, this simple and black hat, without braid or embellishment. With Bonaparte, and this is a rare thing in history, the title never surpasses the myth. It was his character that made legend. A strategist gifted both in the military and in propaganda, Napoleon had a character that easily accommodated himself to precisely what set him apart from the crowd. For him, creating and maintaining this image should therefore only be a habit that is as daily as it is natural, a habit carried by a recurring outfit that regularly spares him the convolutions that so often come with the visits of wardrobes. This is evidenced by the number of bicornes he used throughout his life: from 1800 to 1812, he had between 120 and 160 delivered, which, at most, makes a dozen per year. Let us count those he lost on the battlefield and this consumption appears to be quite reasonable, almost thrifty if we compare it to the expenditure of the monarchs before him for their toilets. The stingy Letizia (1750 – 1836) must have had genes as determined as her son.

Tirelessly dressed in his gray frock coat – our man had few of them and the last was mended relentlessly even in Saint Helena – Napoleon’s black hats were more inclined to adapt, very lightly, to fashions. To such an extent that the painter Charles de Steuben (1788 – 1856) painted around 1826 a “Life of Bonaparte” through his cocked hat!