First of the Bonaparte siblings, Joseph (1768 - 1844) was also the closest to Napoleon. The eldest of the family had a taste for the arts more than for power, and it is undoubtedly for this quality that the United States gave him the best years of his life.

The Departure

Joseph Bonaparte did not have time to take advantage of his privilege as a big brother for long. The young Napoleon, born a year after him, would turn upside down his life and that of his family. Although these two were bound together all their lives by a deep brotherly love, the younger often bullied his elder. The latter always tolerated wickedness with a patience that should command respect. The two were a pair, however, one climbing the ladder of power while the other remaining in the shadows amassed fortune and distinction, serving his brother’s ambition more out of loyalty than taste. Although he certainly had a taste for diplomacy, a quality one would imagine to be necessary when it came to living and working in the circle closest to Napoleon. Joseph, who was determined not to anger anyone, certainly had every opportunity to perfect this art during the reign of his brother. In turn, he was ambassador, senator, king of Naples, then leaving Italy for Madrid, he became king of Spain, general lieutenant of the kingdom in 1814 and finally president of the Council of Ministers during the Hundred Days. The fall of Napoleon was not, however, quite his. With his voluntary exile in America, Joseph was going to begin the best years of his life, more than twenty years of daily savoring what he liked the most, reading, receiving and living comfortably surrounded by art and friendly people.

Overnight between July 24 to 25, Joseph left the French coast, leaving behind his brother, whom he would never see again. He embarked for New York on a discreet brig with his aide-de-camp, his cook and his interpreter James Carret who left to posterity some notes on their Atlantic crossing, notes which set the tone for the comfortable future that will be offered to Joseph in the New World. The trip was pleasant and punctuated, according to James Caret, with the poetic enthusiasm of Joseph, who brilliantly recited French as well as Italian poetry, declaiming entire passages from Tasse, Racine or Corneille without any oversight. Joseph’s memory seemed to be as powerful as his voice, certainly intoxicated by the vastness of the ocean, chanted as if he wanted to be heard from both the old and the new continent.

Arrival in New-York

He first set foot in America on August 20, 1815. Newly arrived in New York, Joseph’s new life, to be pleasant, had to be discreet. The fall of the Emperor and his exile had ushered in a new era in Europe, and times did not spare Bonaparte’s former relatives and supporters. Joseph was perfectly aware that he had to keep a low profile and adopted for his peace of mind the name of Comte de Survilliers. The title was not usurped as it was that of a small property that Joseph owned near Mortefontaine, his French beloved estate. Throughout his stay, even after he was discovered as the brother of the fallen Emperor, he retained this name by which he always presented himself in America.

In New York, he introduced himself to Mayor Jacob Radcliffe, who urged him to come to Washington and make known his kind regards to President James Madison (1751 – 1836). For Joseph in fact had no political inclinations in America, quite the contrary! But as was to be expected, the reception was reserved. On his way to Washington, a messenger came to meet the elder Bonaparte informing him that the president could not receive but that he wanted to assure Joseph that he could remain in the United States as long as he pleased if he remained discreet. It was obvious to Joseph and even rather a wish than a condition. So he turned back to where he came from.

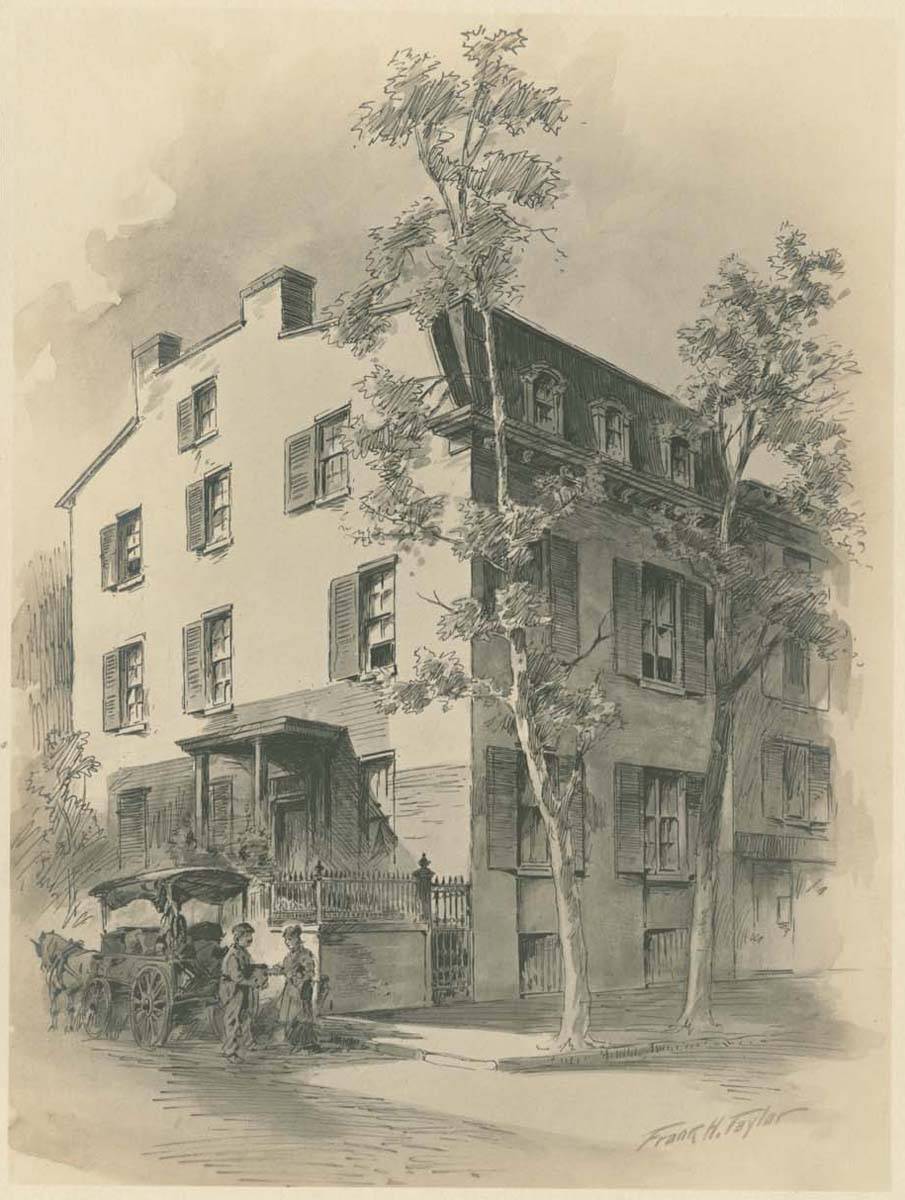

Some time later he left New York (where he was unwillingly recognized as the former King of Spain) and found a home in Philadelphia, at the corner of Second and Markets Street.

This residence hosted Bonapartist refugees as well as other passing French throughout the stay of the former King of Naples. But one never maked waves, visitors always prefered finding in Joseph’s home the comfort of speaking French language as finding the customs and traditions that made French culture. For Napoleon’s brother, the residence was ideally located about fifty kilometers from the land he had just acquired in Bordentown (New Jersey) and which he was busy developing. The house would soon become a benchmark of good taste and French art de vivre because Point Breeze estate, owned by the Count of Survilliers, was for Joseph the work in which he invested much of his fortune but even more himself.

Conveniently located along the Delaware River, in a beautiful landscape, Point Breeze estate required four years of development during which Joseph spared no effort. Supervising the work himself, it was not uncommon for him to show up dusty and in mud-covered clothes, far away from the distinction befitting the duties he had once held. The park was cleaned, fitted out with walks, gardens and flowerbeds. Inside, paintings, bronzes, marble busts, statues and tapestries amazed visitors who were astonished to discover the rooms and lounges, one more elegant than the other. Frances Wright, an English visitor, gave a precise description of reception rooms in the house. Each was furnished with superb mahogany pieces in the finest French style that we now call Consulate and Empire (link). The billiard room was probably the one that Joseph liked most because he spent a lot of time there with his guests. Adorned with white curtains edged in green, the carpets on the floor were white and a very beautiful red. On the walls we admired paintings by Rubens and Vernet, the palettes of which were not to clash with the colors of the room.

Adjacent to the billiard room, the Great Hall was the privileged place for large receptions. The most beautiful pieces of furniture were there, the walls hung with the same blue fabric that covered the armchairs and benches. In the center of this sumptuous room, two spectacular tables with marble tops – gray for one and black for the other – presented a superb collection of bronzes. It seems that a white marble fireplace donated by Cardinal Fesch (1763 – 1839) was also installed in this elegant room. On the floor was a Goblin rug so large that it covered almost the entire surface of the room. And everywhere masterpieces, objects and works of art of the highest quality adorned walls and furniture with a taste that made a visitor tell out loud what many were secretly thinking, namely that Point Breeze was arguably the most beautiful estate of America.

Patron of the Arts

Joseph won unanimous support everywhere. This refined man charmed with his wit, his discretion and his liberality. Certainly because our Bonaparte never failed to open the doors of his home to passing visitors, to curious people, to neighbors and even to artists eager to admire or copy the superb masterpieces which made all the salt of Point Breeze. His desire to promote French and European art through his collection did not stop there. Anxious to show to many people as possible the paintings of the most famous masters in his collection, between 1822 and 1829 he loaned several paintings to the annual exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts in Pennsylvania. His Bonaparte crossing the Grand Saint Bernard signed by the hand of the famous Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825) was presented each year and it was considered by the painter himself as “a great honor”. But Joseph Bonaparte, as a great connoisseur and patron that he was, knew the importance of not underestimating the unknown artists who would perhaps make the famous names of tomorrow. Thus, he welcomed painters artists, both professional and amateur, but one anecdote conveys better than words Joseph’s still keen interest in art rather than ostentation. One day when the young apprentice George Robert Bonfield (1805 – 1898) was sent to Point Breeze for some job, the young man took advantage of a few stolen moments to copy down into a small notebook – which he kept near him – details of a Shipwreck of Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714 – 1789). Joseph passing by surprised the apprentice who had great difficulty in hiding his drawing in time; Joseph then asked to see the notebook and George sheepishly handed it to him. He later rejoiced at this awkwardness because Bonaparte, impressed by the young man’s talent, allowed and encouraged him to draw whatever he wanted in the house! Bonfield made a career and later became an important cultural figure in Pennsylvania.

You have to imagine what the possibility of drawing and reproducing the masterpieces from the Point Breeze collection meant for our young painter. Because if David’s painting was certainly one of the most spectacular, one could also admire works by the hand of Correggio (1489 – 1534), Titian (1490 – 1576), Pierre Paul Rubens (1577 – 1640) or Antoine van Dyck (1599 -1641), of Vernet and David Teniers the Younger (1610 – 1690) as well as Paulus Potter (1625 – 1654), Charles-Joseph Natoire (1700 – 1770), Jean-Baptiste Wicar (1762 – 1834) or François Gérard (1770 – 1837). Without counting the tapestries of the Gobelins, the bronzes and sculptors of the greatest names such as Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822) whose Joseph possessed a bust of Madame Mère (Letizia Bonaparte), a bust of Pauline Borghese and one of Napoleon, of which several visitors admitted that at first glance it was difficult to say whether it was a bust of the Emperor or of his brother as the resemblance between the two was striking!

Point Breeze therefore appeared, in fact, as an emblem of French taste in general but more broadly as the refined taste of the Old Continent, bearing the memory of the former lives of Napoleon’s elder brother whose artworks, it must be said, were not always added to his personal collection in a very legitimate way… But times were different and so were mentalities!

In America, he was not held against him and we constantly marveled at his collection and his library (then the largest in the United States since that of Congress had only 6,500 volumes while that of Joseph had more than 8,000 !) as well as on jewels and gems whose provenance was still questionable… Whatever! We weren’t going to take offense at this affable and courteous man who gave work to all (it was said that in Bordentown there were no poor as long as Joseph Bonaparte lived there). Every Sunday, the doors of the residence were opened wider and opened the vast park along the Delaware River to residents of the neighborhood who did not deny themselves their pleasure! The delights of the gardens in summer were matched only by the frozen lake in winter. In what is now known as Bonaparte’s Pond, one skated happily on the thick ice while Joseph rolled apples on it, which the skaters enthusiastically chased.

The inhabitants held the Comte de Survilliers in high esteem and never missed the opportunity to greet him when he passed by on horseback – an activity to which he was very attached – and, for his birthday, a brass band was sent to him from the locals. We couldn’t ask for a better neighborhood in Bordentown. Bonaparte did not like discord or aggressive confrontations, always preferring arrangement and negotiation. One example: when the railroad came to pass through his Point Breeze lands, he did not even consider a lawsuit that promised to be as long as it was uncertain. He settled out of court an inconvenience that became a source of profit: in exchange for the train to pass through his property, Joseph obtained a thousand shares in the Baltimore railway company. All his life, the elder brother of the Bonaparte family had shown remarkable intelligence in business, thus accumulating a colossal wealth which allowed him to live in more than luxurious comfort without having to worry about a thing. Although the phrase is exaggerated, it has been said many times that Joseph Bonaparte was the richest man in the United States, which already says a lot about what this character showed of himself to other people.

Taste of America

Joseph had arrived in New York without his wife Julie Clary (1771 – 1845) who never joined him there. In fragile health, she preferred to settle in Switzerland, in Brussels and then in Florence, where Joseph would find her at the end of their life. If American society was full of praise for the former King of Spain, we can at least say that it was careless about the very personal notion that the man had of marital fidelity! Annette Savage (1800 – 1865), whose Quaker family claimed to be descended from Princess Pocahontas, was his first mistress in the New World. Two children were born from this union: Caroline Charlotte in 1819 and Pauline Josèphe in 1822. He also fell in love with Émilie Hémart, wife of one of his lawyers (who was clearly not destined to become a divorce professional). Émilie gave birth to Félix Joseph, born in 1825. Either way, Joseph never neglected his children and always made sure that they lacked nothing.

It is easy to understand from studying his American life why Joseph Bonaparte said he was spending the best years of his life at Point Breeze. To Frances Wright, our English visitor, who pointed out to him that he seemed very happy to be busy embellishing his park and his house, he gave her a colorful response. As he plucked a small wild flower, he compared this tiny beauty to the pleasures of privacy while the showy blossoms in the flowerbed reminded him of ambition and power that he felt presented better from afar than near. He will always remember this American happiness and his friends there. It was moreover as a friend that he was gradually considered, until he was received at the White House by Andrew Jackson (1767 – 1845) not as a political refugee but as a friend of America. It was also in this same spirit that he was admitted in April 1823 to the American Philosophical Society founded by Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790) in 1743.

Yet he lived through discouraging and painful times there. The fire which ravaged his home on July 4, 1820 was dramatic without however destroying it completely, reassured that it was by the help and the kindness of the inhabitants of Bordentown, what he testifies in a letter to the mayor, William Snowden:

You have shown me so kind an interest since my arrival in this country, and especially since the incident of the 4th of this month, that I am sure you will be willing to say to your fellow citizens how greatly I am touched by what they did for me on that occasion. I being absent myself from home, they hastened, of their own accord and at the first alarm, to overcome the conflagration ; and, when it became evident that this could not be done, they directed their efforts to save as much as possible of what had not been already destroyed. The furniture, the statues, the pictures, silver, jewels, linen and books, in fact everything that could be brought out, were placed with the most scrupulous care under charge of my servants. Indeed, all through the night, as well as upon the following day, boxes and trays were brought to me which contained articles of the greatest value. This proves to me how clearly the inhabitants of Bordentown appreciate the interest that I have always taken in them.

The Count of Survilliers rebuilt a second house on the same land. It was in this home that he learned of his brother’s death in 1821 and his mother’s death in 1836, two ordeals for Joseph. For if he didn’t show it, didn’t talk about politics, and pretended not to care (at least for a while), the loss of his younger brother and his mother were undoubtedly painful trials. After a brief return to Europe from 1832 to 1835, he returned to Point Breeze where he lived for another five years until 1839. The death of his own daughter Charlotte in 1839 followed shortly after by that of his dear uncle Joseph Fesch then (only 5 days later) the death of his sister Caroline decided him to return to Europe for good. He eventually joined his wife Julie in Florence in 1840 and lived there for the last few years suffering regularly from stroke before falling into a coma on July 27, 1844 and dying the following day.

When he left the United States for good, he left nothing but good memories. Several of his friends received wonderful gifts from him from his superb collection of artworks and art objects. A large part of these gifts are now exhibited in American museums and one even find in the White House, at the entrance of the Red Room, a mahogany console that Jacky Kennedy particularly appreciated and which was first the property of Joseph Bonaparte. At auctions, a few objects sometimes reappear, testifying to the pomp and assured taste of Napoleon I’s elder brother. Joseph Bonaparte will never cease to assure himself that he lived, in America and at Point Breeze in particular, his best years. Praising the prosperity and beauty of this country, he undoubtedly appreciated the possibility of being himself at last. Now freed from the obligation to serve his brother’s consuming ambition, America was for him the land of a new life – light, luxurious and comfortable – a much coveted life as a gentleman farmer.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Congratulations!

You are now registered to our Newsletter.

Marielle Brie

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».