"Speed, speed, speed". These words of Napoleon Bonaparte could succinctly summarize the essence of his strategic genius. The Napoleonic army moved twice as fast as its adversaries. An asset as much as a feat, both supported by an accessory showing itself (almost) always failing: the soldiers' shoes.

Doubtless no campaign was exhausting like the Napoleonic campaigns. That a good physical condition is essential to make a good soldier, no one will doubt it, but more than for any other, the conscripts of the Napoleonic wars had to have an iron health. Probably, no one imagined the harshness and endurance required that soldiers would have to display to face the forced marches on often bad and chaotic terrain.

Conscription then concerned young people aged 20 to 25, in good health naturally. Drawn by lot, the conscripts designated by Fortune – whose good intentions can legitimately be questioned – had to be trained quickly to integrate regiments made up of young and old experienced soldiers. At the cost of intensive and severe military training, it took three months of service to make a recruit into an effective infantryman. However, the very first teaching provided often consisted in differentiating his right foot from his left foot, a rudimentary exercise but essential for the good soldier to walk correctly in step. For these young people, mostly uneducated and more versed in the art of working the land than moving around it in an orderly and synchronous manner, the instructors found a trick that put at the center of the future soldier’s life an accessory that would focus their attention steadily until they return, perhaps one day, to civilian life: the shoes. In the left shoe (or the hoof for those who were not yet perfectly equipped) we placed straw while the right shoe was stuffed with hay. Thus, the soldier went at a walk without being mistaken at the chanted cry of his superior “Straw – Hay!” Straw – Hay! “. The attested anecdote has something to smile about if the problem of shoes in the Napoleonic armies had not become a permanent concern for the General Staff.

The Napoleonic marches

The Napoleonic campaigns to be dazzling must be led by enduring soldiers, without injury and therefore well equipped. Because the steps are terribly long. Linking one city to another, one battlefield to another, often involves traveling tens of kilometers a day in a very short time at a sustained pace. The feat of the troops of General Friant (1758 – 1829) compelled admiration in this sense when his troops rallied the battlefield of Austerlitz by covering more than one hundred kilometers in 44 hours. On average, the troops traveled 50 kilometers daily in often difficult conditions (terrain, climate). We therefore understand the capital importance for soldiers to be well shod.

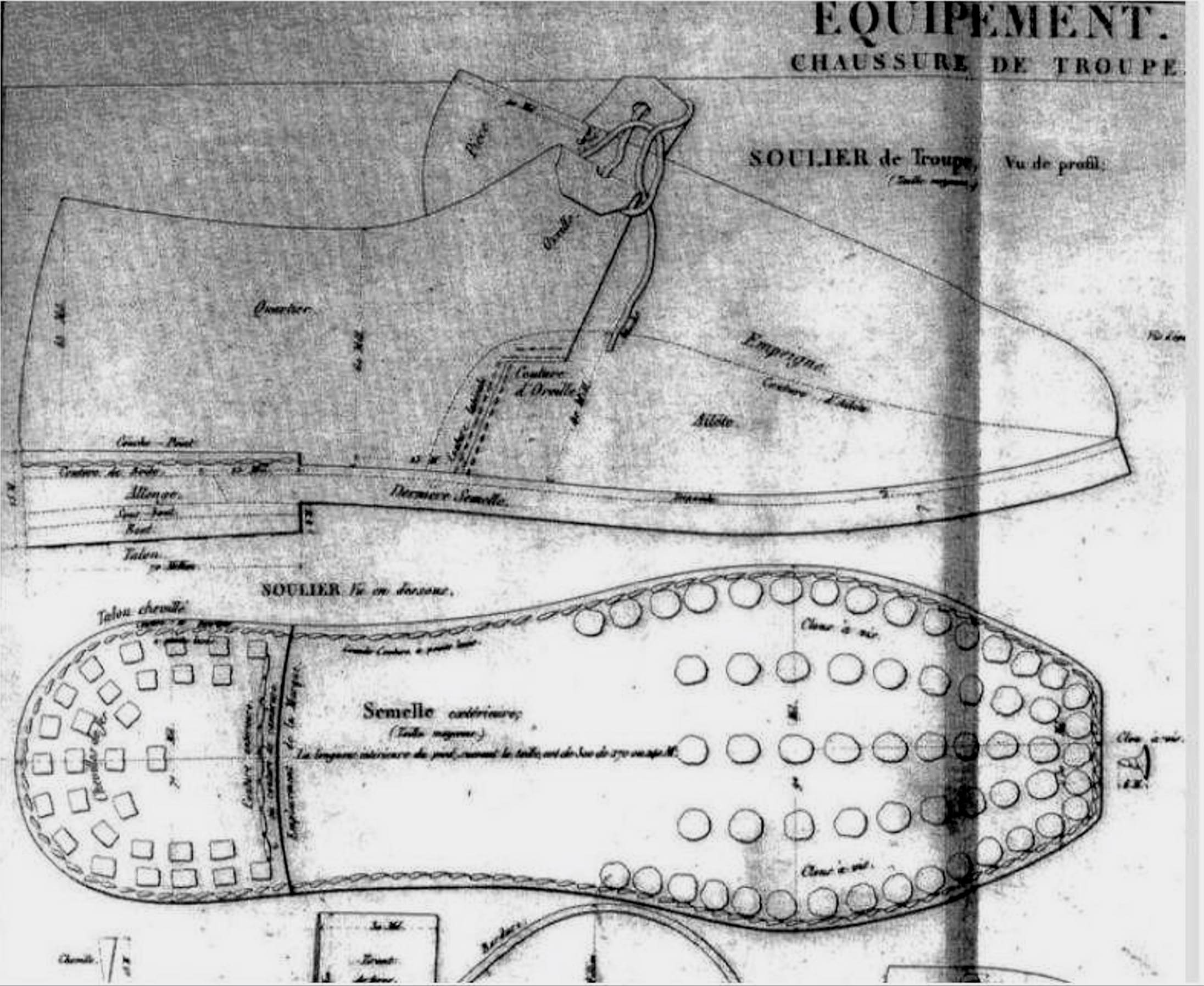

The shoes distributed by the Army were made of turned cowhide and weighed 611 grams (only, one might add). They were of three sizes ranging from small (between 20 and 23 cm) to large (over 27 cm) through a medium size (between 23 and 27 cm). The last sole was in tanned cowhide leather then reinforced with shoemaker’s nails: there were between 36 and 40 depending on the size. The soldier tied them firmly with a leather lace passing through two holes without eyelets; wear was to come to an end very quickly. Like almost all shoes from this era, the toe was square. A peculiarity all the same specific to the military shoe: there was neither right nor left foot. The two perfectly identical shoes were shaped by the foot of their wearer according to the grueling steps he took. Thus, each new recruit was given a uniform, a weapon and of course a pair of shoes normally designed to travel a thousand kilometers.

But the latter were worn out so quickly that numerous testimonies report that at the end of the fighting, the soldiers hastened to remove the shoes of the dead when they did not make their own shoes with the means at hand. During the Spanish Civil War, spare shoes did not arrive, the soldiers became shoemakers in addition to their usual duties. In his Briefs , David Victor Belly de Bussy (1768 – 1848) reports that men made boots for themselves by rolling cowhide around each leg and foot, taking care to leave the animal’s hair out.

Thus, despite the importance that Napoleon Bonaparte always attached to the good equipment of his troops, the stewardship took under the Empire such an extent that the financiers struggling to win military contracts had no qualms about providing poor quality equipment. for the bulk of the troops. Not to mention the problems associated with supplies, soldiers’ shoes were a constant concern and a recurring subject in Napoleon’s correspondence.

The unscrupulous suppliers of the Napoleonic army

The contracts signed with the army were juicy for those who had the means to pay the advances and to come to an understanding in unofficial politics. Corruption and the friendships of a close circle of power were absolutely necessary for anyone aspiring to do business.

For the Italian campaign, it was the Coulon brothers, friends of Bourienne (1769 – 1834) who won the market for soldiers’ shoes, but their bankruptcy put an end to this contract. Before the Battle of Marengo, a treaty was signed with Étienne Perrier and his counterpart Louis Cerf, both shoemaker and bootmaker. These two Parisian artisans were responsible for supplying Hungarian-style shoes and boots to the Army corps. But it was undoubtedly Arman-Jean-François Seguin (1767 – 1835) who won the biggest contract. This chemist had succeeded in developing a rapid tanning process that required only three weeks instead of the traditional six months. Naturally, this innovation attracted the attention of the State, which granted Seguin the market for “all the tanned, wrought and honed leathers necessary for the footwear and the equipment of all the troops on foot and on horseback” for a duration of 9 years from year VI (1796).

These markets with insubstantial economic benefits were not, however, inspected as one might expect from a state order. The financiers therefore made a point of reducing the quality of the products in order to make more profit. The case of the cardboard shoes seems to start off as a joke, but it is not.

For the Russian campaign, the soldiers of the Grand Army were given faux leather shoes with cardboard soles. What would have been an annoyance in Spain turned into a frozen nightmare in Eastern Europe. Gabriel-Julien Ouvrard (1770 – 1846) one of the most important financiers of the time – a character that Bonaparte did not like but needed – was suspected of being at the origin of this dishonest and contemptuous delivery. It seems that no proof can yet formally attest to this.

Napoleon Bonaparte's boots

The soldiers were thus the worst shod. But the higher we rose in the military hierarchy, the more we favored the comfort of our feet (among other things). The highest ranks were gaiters and boots, although the quality was not always there. If necessary, the emoluments however made it possible to afford a pair made of good leather.

Napoleon I never distinguished himself on the battlefields or during the campaigns by an inappropriate luxury and naturally his taste went to simplicity. He always favored quality although he was often negligent. His shoemaker Jacques, installed rue Montmartre in Paris, said that Napoleon had the nasty habit of stoking the fire in the bivouacs with the tip of his boot, thus wearing out many pairs which, without this wicked treatment, would have lasted a long time. Bonaparte attached himself a model of high boots to the rider – supple boots with cuffs – in black morocco which he ordered in numerous copies. He wore a current size 40 and paid them 80 francs, which is 20 francs more than the famous black beaver hat (link). A tidy sum for the commoner, but almost too low for an Emperor whose taste for simple things must be recognized – at least.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Congratulations!

You are now registered to our Newsletter.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».