Inseparable from Napoleon I, the Empire style not only brings together similar and concomitant stylistic characteristics in the fine arts, furniture and decorative arts. The Empire style is both the fruit of a political context which Bonaparte knew how to seize and the very illustration of this success. A success that will appeal well beyond French borders.

The genesis of the Empire style

In the 1720s, the return to antiquity began in Italy with a scholarly enthusiasm for Etruscan culture that two Tuscan scholars, Filippo Buonarotti (1661 – 1733) and Anton Francesco Gori (1691 – 1757), claim to be the common ancestor of Greek and Roman art. The doctrine seduces Italy, or rather a learned and easy Italy having all the leisure to take an interest in the subject. In 1738, Charles de Bourbon (1716 – 1788) initiated the excavations of Herculaneum discovered in 1709. Ten years later, it was Pompeii that they decided to excavate (without being able to first assume the full richness of this idea). The whole of Europe is passionate about these sites which reveal the most exquisite treasures every day. To feed their spectacular collections, the English lords bribed antique dealers (Lord Hamilton’s collection would form the basis of the collections of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum) but the French were not to be outdone. In European courts, nothing is now more chic than the neoclassical. Not that the ancient references had disappeared, they have been the very vocabulary of classical art for a very long time already. But it is in Herculaneum and Pompeii new and sober lines which commit artists and craftsmen to more simplicity. From the rich and opulent Louis XV style to the fine and elegant Louis XVI style, fine arts, furniture and decorative arts are all subject to this new calm borrowing from the silent grace of ancient discoveries.

Napoleon Bonaparte was born in 1769, sixty years after the discovery of Herculaneum and twenty-one years after the start of excavations at Pompeii. The taste for the antique is the cultural normality of his youth, a necessary institution. Like any person of quality (or who claims it), he receives an education modeled on that of the aristocrats and based on reading the classics. The young men who will mark the Revolution and the beginning of the 19th century read ancient authors, they learn Latin (which Napoleon knows) and sometimes Greek (which Napoleon does not know). The history of the great ancient cities such as Sparta, Athens or Rome holds no secrets for this youth brought up in the admiration of antiquity, artistic first but also political soon …

From the Revolution to the Directory: a dormant style

Once the Revolution was over, the country’s economic situation did not suddenly recover under the Directory (October 1795 – November 1799). The consequences are painful in the various sectors of art and crafts. Although the abolition of privileges has led to the abolition of corporations, economic activity, if it is favorable to a few, leaves the majority in a precarious and delicate situation. The political upheavals and the rise in prices hamper artistic production which weakly initiates a change of style. The nouveau riche bought the furniture of the emigrant aristocrats and fitted out interiors, the few novelties of which further refined the Louis XVI style. The symbols of the Revolution (Phrygian cap, lictor’s bundle, cockade, etc.) rub shoulders with an ancient vocabulary made up of urns and amphoras, mermaids, griffins and allegories such as Fame and Renaissance, two figures that ‘we hope promising …

The simple and light forms are of a sobriety close to restraint. The Directoire style sign with grace the discreet transition from the glitzy Louis XVI style to the imperious Empire style. Nevertheless, personalities (often female) stand out and rekindle interest in an artistic dynamism capable of frankly breaking away from the lines of the Ancien Régime. Among these personalities stands out the soon to be famous Joséphine de Beauharnais (1763 – 1814).

In March 1796, Josephine civilly marries her pretender general . In love, Bonaparte quickly leaves her: the Italian campaign begins (1796 – 1797) and with it, the Napoleonic legend. It is followed by the Egyptian campaign (1798 – 1801). The young and fiery general is victorious everywhere, and not just on the battlefield. His keen sense of communication absorbs the culture, politics and economic context of his time as well to produce propaganda that goes well beyond rave military bulletins, of which he is also the author (we are not never better served than by oneself). The analogy with Julius Caesar (circa 100 – 44 BC), initially shy, gains in confidence. And for good reason. The brilliantly won battles in Italy, birthplace of the Roman Empire, shed light on this strategic general who also appears to be a formidable politician. Like Julius Caesar during his conquest of Gaul, Bonaparte acquired the full support of his army, which respected him for his obvious military qualities and for his proximity to his soldiers. This man, his soldiers do not hesitate to crown him “little corporal”, a distinction having in their eyes much more value than the highest rank. The general’s successes reached France in a growl that was more and more unpleasant to the ears of the Directory. The popular enthusiasm is palpable. Stendhal is not mistaken when he writes in The Charterhouse of Parma :

On May 12, 1796, General Bonaparte entered Milan at the head of this young army which had just crossed the Lodi bridge, and told the world that after so many centuries Caesar and Alexander had a successor.

In Italy, he confiscates ancient and modern works of art from this country which, it is claimed in France, can no longer claim the heritage of the great Roman Empire. His heirs are no longer in Italy and a song of 9 Thermidor Year VI (July 27, 1798) corrects a historical geography deemed erroneous, proclaiming:

Rome is no longer in Rome,

She’s all in Paris!

An affirmation which will obviously generate an unreserved enthusiasm for the antique in art and crafts. Since General Bonaparte is the new Caesar, hay for all the symbolism of the Ancien Régime! Roman antiquity is full of iconographic wealth, freshly and opportunely discovered, not to mention the wonders brought back from the Egyptian countryside… Let’s say Antiquity in its entirety! Sphinxes, winged lions and scarabs now enrich the vocabulary of furniture and decorative arts dominated by a repertoire inspired by Greek and Roman Antiquity. The carpenter Georges Jacob (1739 – 1814) who had made seats inspired by Greco-Roman antiquity in the 1790s is back on the scene. The solid mahogany dominates the luxury furniture whose tawny shades enliven the strict lines evoking ancient architecture. Marquetry, if it does not disappear completely, is no longer in fashion. Bronzes with Greco-Roman or Egyptian motifs punctuate these pieces of furniture, some of which are making their very first appearance. Thus the boat beds, mirrors in tilting feet called “psyche” are installed in the rooms and the toilets. The pedestal table brought back into fashion by the Directory became essential under the Consulate before becoming the centerpiece of the Empire salons.

When the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire Year VIII (9 November 1799) overthrows the Directory in favor of the Consulate, the Empire style, which does not yet bear its name, is already well on its way …

From Consulate to Empire: a European style

Like Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte was first appointed First Consul for ten years before obtaining this title for life, in 1802. Like Caesar, Bonaparte undertakes to assert his civil power as much as his military power: he undertakes strong reforms and intends that they be implemented quickly. Court ceremonies and protocol are again in order. At Malmaison, acquired in 1799 by Joséphine, the First Consul sent his two architects Charles Percier (1764 – 1838) and Pierre Fontaine (1762 – 1853) to practice their art with the desire to create a style freed from the memory of royalty. The “Roman” style layout of the Council Chamber is a masterpiece that has remained intact.

The arrangement and decoration had to be completed in ten days of work, because they did not want to interrupt the frequent trips that were to be made. [Bonaparte] used to do there; […] It seemed appropriate to adopt […] the form of a tent supported by pikes, beams and signs, between which are suspended groups of weapons reminiscent of those of the most famous warrior peoples of the globe

Percier and Fontaine, Collection of interior decorations .

Everything is there: the celebration of military valor (the helmets on the firewalls, the beams and pikes), the evocation of all the antiques (the heads of lions and winged lions, the Athena clock, the hand painted panels Pompeian) and the solemn, serious and efficient aspect of the legislator. No frills, everything is efficient, up to this hot water bottle lamp (named after a set of three of a kind) placed in the center of a circular mahogany table and furnished with curule seats and “Return from Egypt” armchairs. »Whose uprights are hieratic sphinxes. Note that those presented today in the Council Chamber come from a series of six from the Saint-Cloud Palace and were placed in the Council Chamber at Malmaison by Napoleon III.

The Empire style is not very far now and the approach of its advent can be counted in months …

An anonymous (who is none other than Napoleon’s brother, Lucien Bonaparte) already published in November 1800 a Parallel between Caesar, Cromwell, Monk and Bonaparte , well-written work, supposedly “translated from English” (and ironically, strongly anti-English) and in antique fashion (again her). The book clearly prepared the ground for the arrival of the big brother to the highest political office:

There are men who appear at certain times to found, destroy or repair empires. There is something so extraordinary about their fortune that it draws in its train all those who at first thought themselves worthy of being their rivals. Our revolution had so far given birth to events greater than men (…). For ten years, we had been looking for a firm and skilful hand that could stop everything and support everything (…). This character appeared. Who should not recognize Bonaparte? His astonishing destiny has more than once compared him to all the extraordinary men who have appeared on the stage of the world. I do not see any in the last few centuries that bear any resemblance to him.

Finally, and like Julius Caesar again, Bonaparte was given the title of Emperor (by the senatus-consulte in May 1804), thus putting an end to the first Republic established in 1792. From then on, the parallels with Rome and Caesar will be systematic. For Napoleon I, it was first of all a question of ruling out any possible parallel with royalty. The semantic field of power and its representatives now borrows everything from ancient Rome, from the Senate to the prefects. However, Bonaparte refuses perfect assimilation: the borrowings must be only cultural, semantic but above all not political because he does not forget the wrongs of the Roman emperors:

What a horrible memory for the generations that that of Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, Domitian, and of all the princes who reigned without legitimate laws, without transmission of heredity, and, for reasons useless to define, committed so many crimes and weighed heavily so many evils in Rome.

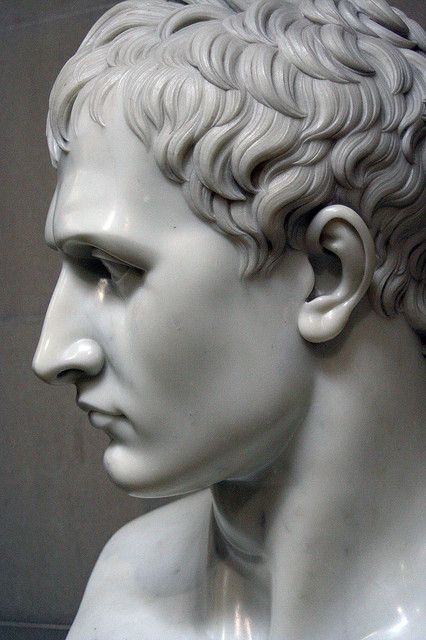

The Empire style will therefore not be the Roman style and if the first will borrow from the second, it will never be a reincarnation. The busts and portraits of the Emperor are magnified in a memory of this beautiful ideal of ancient statuary, but the comparisons stop there for the figure of Napoleon I. In furniture and decorative arts, the Empire style imposes the simplified volumes that have asserted themselves since the Directory. The furniture becomes imposing and massive, sober and austere, borrowing their lines from architecture. The furniture mainly in mahogany had to adapt to the Continental Blockade imposed by Napoleon from 1806 to 1814. The supply of exotic woods to carpenters and cabinetmakers now impossible, they turned to native woods: walnut, pear, maple, lime, beech, elm burl, yew and ash. Chests of drawers, sleigh beds, consoles and pedestal tables are the emblematic pieces of this style which also offers a superb revival to the art of the seat over which Georges Jacob and his sons reign.

The gondola chair is Joséphine’s favorite, the curule chair is everywhere, the heads of lions, caryatids, swan necks and sphinxes adorn the armrests and the armrests consoles. In the decorative arts, the art of bronze reaches its highest degree of elegance and finesse. Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751 – 1843), modeler and chaser, is one of the most sensitive interpreters of the Empire style. With the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, he became the most important bronzier in France and produced, on a drawing by Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763-1810), the eagles of the First Empire as well as the vermeil cradle of the King of Rome in Saint-Cloud with the help of Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot (1763 – 1850).

Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764 – 1843) is one of the most talented goldsmith of the Empire style. He obtains in particular the exclusivity of the supplies for the table of the Emperor but will use his art in many other objects. Let us mention in particular the Athenian woman whom Napoleon loved so much and who accompanied him, thanks to his valet Marchand (1791-1873), in exile in Saint Helena .

La Malmaison still remains today a preserved jewel of this Empire style. From the dining room to the music room, the architects and decorators Percier and Fontaine used a palette and a vocabulary compiled in their Collection of interior decorations which circulated throughout Europe.

Thus, from 1810 the Empire style became the official style of European courts thanks to the conquests of Bonaparte. This massive diffusion is then greatly facilitated by the neoclassical taste already well established in Europe since the discoveries and excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii in the 18th century. However, this in no way diminishes the strength of the Napoleonic style, the refinement of lines and materials of which imposes a homogeneity of the pieces. This will also be the strength of the durability of this style. Its uniformity resting on solid ancient foundations, the Empire style will never completely lose its charm and the sobriety of the lines will inspire even Art Deco. In the same way that Napoleon Bonaparte knew how to capture the zeitgeist to build his own legend, he made furniture and decorative arts the material and sumptuous memory of the Napoleonic myth. Even today, neither the myth nor the style have aged …

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

Félicitations !

Vous êtes désormais inscrit à notre newsletter.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».