The Vendôme Column

What a remarkable tale that of the Vendôme Column! Erected, toppled, rebuilt; one day an Emperor’s pedestal, the next a standard-bearer of royalty. From pride to regret, from Austerlitz to the Commune, this column has never ceased to stir passions.

Rome, AD 107: the Roman Emperor Trajan (53–117) commissions a marble column to celebrate his armies’ victories over the Dacians. Placed at the centre of the Roman Forum, it recounts, upon a spiralling frieze of sculpted bas-reliefs, the principal episodes of the Dacian Wars (101–102 and 105–106). Completed in 113, it is crowned with a bronze statue of the Emperor. The sculpture later disappears, and from 1587 onward it is Saint Peter who rises in its stead.

Paris, 1798: the architect Bernard Poyet declares that “The republican regime must replace the effect of steeples with columns, obelisks, and monuments whose elevation, attesting to the glory of the Nation under the reign of Reason, shall equal at least those towers and spires once raised by fanatics.”

Austerlitz, 2 December 1805: the Russian and Austrian armies of the Third Coalition are defeated by Napoleon I. Their artillery pieces are seized. They will now serve a project worthy of Antiquity itself—a monument commensurate with the glory of the Grande Armée, and in keeping with the principles proclaimed by Bernard Poyet.

In Memory of the Brave

On 21 March 1800, a first decree announced the erection, “in every département, upon its principal square, of a column in memory of the brave of the département, who died in defence of the fatherland and of liberty.”

The project was perhaps too ambitious; though not realised everywhere, it took on formidable proportions at the heart of the capital. For the “column of the brave” was already underway when Napoleon won the Battle of Austerlitz. Yet the work advanced slowly, materials were lacking, and the timely capture of Austrian and Russian cannons rekindled the enterprise as much as it transformed it.

Vivant Denon, director of the Musée Napoléon (now the Louvre), already oversaw the project. Architects Jean-Baptiste Lepère and Jacques Gondouin were called upon to bring to life this immense column, destined to reach a height of 44 metres.

The painter Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret was charged with designing the bas-reliefs to be sculpted upon 425 bronze plaques, winding upward as on Trajan’s Column. They depict the Boulogne camp facing England, the army’s departure, its battles, and the Emperor’s triumphant return to Paris on 16 January 1806.

At its summit, like its ancient ancestor, the modern column would be crowned with a statue of the Emperor—Napoleon I. The sculptor Antoine Chaudet represented Bonaparte as a Roman emperor, crowned with laurel, a winged Victory in his left hand and a lowered sword in his right.

A Memorable Anniversary

The Vendôme Column was at last inaugurated on 15 August 1810, the anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s birth—a date he no doubt hoped would anchor the monument in eternity. History, however, had other plans. Barely five years later, on 12 April 1814, the Emperor abdicated, and his adversaries hastened to pull down his statue from atop the column, raising in its place the fleur-de-lys banner of Louis XVIII and the restored monarchy.La colonne Vendôme est enfin inaugurée le 15 août 1810, le jour de l’anniversaire de Napoléon Bonaparte qui l’espère sans doute installée pour l’éternité. C’est sans compter les vicissitudes de l’Histoire ! Moins de cinq années plus tard, le 12 avril 1814, l’Empereur abdique et ses adversaires s’empressent de faire tomber sa statue au sommet de la colonne, pour hisser à sa place le drapeau fleurdelysé de Louis XVIII qui marque la Restauration du pouvoir monarchique à la tête de la France.

The “Little Corporal” was exiled to Saint Helena, yet the distance that was meant to dull his memory only served to kindle the legend of the fallen Emperor. Upon the announcement of his death, his popularity proved far too great to ignore. Louis-Philippe seized the opportunity to win favour by placing atop the column a new statue—not of the Emperor, but of the Little Corporal himself, the soldier-leader and military genius in his eternal bicorne, hand tucked into his waistcoat.

This bronze figure by Charles-Émile Seurre, now housed at the Invalides, continues to impress visitors with its bearing and presence. Why, then, did it leave the column? Because Napoleon III—at once nephew and grandson (through his maternal grandmother Joséphine) of the first Emperor—ascended the throne in 1852 and wished for his illustrious predecessor a representation that did not obscure his political role in the nation’s history. Seurre’s Napoleon thus yielded, in 1863, to the sculpture by Auguste Dumont. Yet again, this would not last.

The Fall of the Vendôme Column

The Franco-Prussian War brought about the downfall of Napoleon III’s government; he was taken prisoner on 3 September 1870. The new authorities rejoiced too soon, for the Paris Commune, between March and May 1871, overthrew both the National Defence Government and the Vendôme Column itself. The monument was denounced as a “symbol of brute force and false glory” and, after great difficulty, was sawn down on 16 May—only to be swiftly regretted.

The Third Republic ordered its restoration and re-erection, placing the cost of this colossal work upon the painter Gustave Courbet, unjustly accused of having ordered its destruction. The bill was steep: over 320,000 francs, payable in annual instalments of 10,000 francs for 33 years. Too great a sum for one man: Courbet died on 31 December 1877, before paying even the first instalment of this accursed column, which once again towered over the Place Vendôme from 18 December 1875 onward.

From Austerlitz to the Place Vendôme, the column witnessed as many victories as defeats—those of nations as well as individuals. Classified as a Historic Monument since 31 March 1992, it remains today an unmistakable landmark of the Parisian landscape, as surely as the Alexandre III Bridge. Though it cannot be visited, one should know that the staircase within leads to a terrace offering one of the most splendid views of Paris.

Battle of Austerlitz

Throughout the world, in all its retellings, one admires the military genius of the famed Corsican: the Battle of Austerlitz crowned Bonaparte victor exactly one year to the day after he donned the imperial diadem.

The second of December marks not merely the anniversary of one of France’s most resplendent military triumphs. It marks an era in which the map of power in Europe was redrawn. For this reason, the Battle of Austerlitz stands as a major historical event that confounded every prediction.

Never two without three: the Third Coalition

Formed in July and August 1805, this alliance united Britain, Russia, Austria, Naples, and Sweden. It followed, quite logically, the First and Second Coalitions—likewise instigated by Britain and directed against post-revolutionary France.

The Franco-British conflict between 1803 and 1805 arose for several reasons (the economic blockade imposed on Britain by France, the protectionist and annexationist policies pursued by the Hexagon toward the lands of its closest neighbours), and it ultimately led to the creation of the Third Coalition. For when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor on 2 December 1804, annexed the Italian city-states of Parma and Piacenza, and proclaimed himself King of Italy on 17 March 1805, France’s ambitions became unmistakably clear to its European neighbours.

From 1803 until August 1805, the Grande Armée encamped at Boulogne, casting the shadow of an invasion across the Channel. It broke camp when the Third Coalition was formed, which planned first the junction of Austrian and Russian forces in Bavaria. Napoleon outpaced this movement, transporting his troops to encircle the Austrian army at Ulm, which capitulated on 20 October 1805. Now Napoleon had to confront the Russians under Mikhail Kutuzov, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Russian Army, as well as Austria’s reserve forces.

The Sun of Austerlitz

The French Emperor was in no comfortable position. The day after his victory at Ulm, his fleet suffered defeat at Trafalgar. By mid-November, the Grande Armée—having only just entered Moravia—could not prevent the union of Kutuzov’s troops with those of Alexander I of Russia and Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire. A major confrontation loomed, and it did not favour the French.

With the bitter cold of early December 1805 came the first anniversary of the Emperor’s coronation. Celebrations were held on the eve of battle, even as the Grande Armée found itself outnumbered and manoeuvring deep in enemy territory. Everything seemed to stand against it. Napoleon therefore adopted a strategy that combined deception with an exploitation of the enemy’s weaknesses. He resolved to make a deliberate blunder so that the adversary might commit a far graver one.

The battle began at dawn to the south-east of Brünn. The enemy had massed on the Pratzen Heights, while the French occupied the lower ground. Napoleon weakened his right flank to entice the enemy to descend from the plateau. This they promptly did, despite Kutuzov’s warnings—well-founded, as it proved—that this was a tactical ruse.

His counsel went unheeded, and the Austro-Russian forces rushed down the heights, abandoning their defensive system in the hope of encircling and cornering the supposedly weakened French right. Napoleon feigned a retreat, encouraging the two emperors to press a rapid attack. Little more was needed to set disaster in motion. Napoleon then ordered the assault on the heights. His troops emerged from a mist that had favourably concealed their numbers from the enemy. They swept aside the few defenders who had remained. As a brilliant sun rose in the sky, the Russians struggled for hours to retake the plateau, in vain. Forced into retreat, some troops attempted to flee across frozen lakes; French cannon fire shattered the ice so effectively that all perished by drowning.

Enemy losses were colossal: roughly 35,000 men, against 8,000 French casualties, including 1,300 killed. Nearly all enemy artillery pieces were seized.

The Holy Roman Empire would not recover: the Treaty of Pressburg, signed on 26 December 1805, delivered a fatal blow, and it was soon replaced by the Confederation of the Rhine. Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire became Francis I of Austria. Louis Bonaparte became King of Holland, and his brother Joseph now reigned over the Kingdom of Naples.

The defeat was stinging—humiliating. A little less than sixty years later, the Second Empire commemorated the episode by naming, in 1864, a street near the Champs-Élysées the Rue du Traité-de-Presbourg.

On 2 December 1805, one year to the day after the Emperor’s coronation, this victory was not only decisive for the outcome of the conflict between France and the Third Coalition. Symbolically, it consecrated the strategist-emperor whose military genius was then universally acknowledged. Many perceived in the Sun of Austerlitz a divine intention to make Napoleon I shine. His destiny would later deny it. Until then, the Battle of Austerlitz inaugurated a military legend that continues to inspire volumes.

Soldiers! I am satisfied with you. At the Battle of Austerlitz you justified all that I had expected of your intrepidity; you have adorned your eagles with immortal glory. […] My people will welcome you back with joy, and it will suffice for you to say, ‘I was at the Battle of Austerlitz,’ for the reply to be, ‘There goes a brave man.’

Napoleon I, excerpt from the proclamation after Austerlitz, 12 Frimaire Year XIV (3 December 1805)

How did Napoleon die?

On May 5, 1821, at 5:49 pm, "amidst the winds, the rain and the crashing waves, Bonaparte gave back to God the most powerful breath of life that ever animated human clay." The emphatic Chateaubriand stood out from his contemporaries when Napoleon died.

Exiled to the island of St. Helena since 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte, the deposed emperor, died at the age of 51, at the end of a romantic life that was to leave its mark on history. But were his contemporaries already aware of the fame to come? Nothing is less certain.

How did Napoleon die?

Napoleon’s death has been the subject of much speculation: did his English captors poison him? How did his body remain strangely intact before the stunned eyes of those who witnessed the removal of his remains in 1840? Some have seen this as the workings of a conspiracy, when in fact the great man’s death is no longer such a mystery.

Napoleon was suffering from stomach cancer, the same disease that had claimed his father. Already in his youth, he sensed that this illness, incurable by doctors, would be the cause of his demise. As is often the case, Napoleon was not wrong.

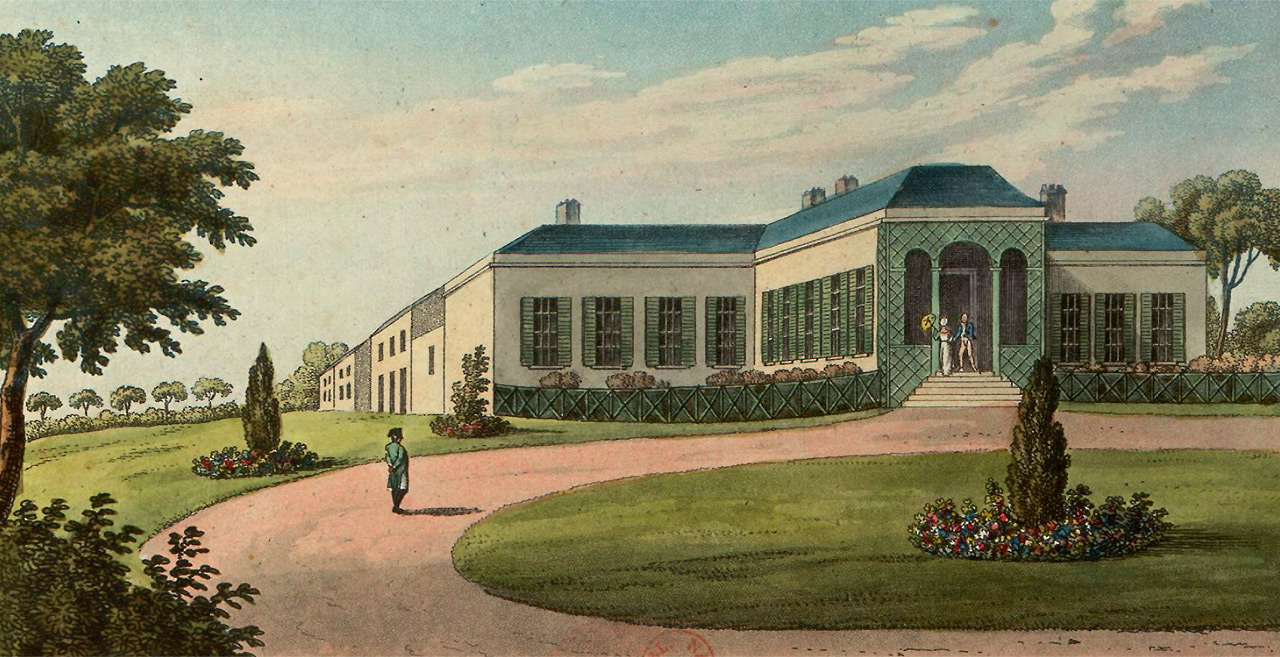

Already, since March 1821, his strength had been waning. Bedridden in his damp, decrepit room at Longwood House, his friends and family were busily watching over him, feverishly monitoring his condition. He ate less and less. As his illness worsened, his body could no longer tolerate food. He refused the drugs the doctors prescribed, too convinced – alas, rightly so – that they would do no good.

When Napoleon breathed his last on May 5, 1821, the body was left to rest until the early hours of May 6. Then, just after midnight, the emperor’s body was carefully washed with his beloved eau de Cologne, mixed with a little water from the Torbett fountain. Napoleon had discovered this fountain in the early days of his exploration of the island.

Aware that his English enemies and jailers would no doubt refuse to repatriate his body to France, where he wished with all his heart to be buried, he found a serenity in this place that pleased him.

[…] if, after my death, my body remains in the hands of my enemies, you will deposit it here.

Napoleon speaking to General Bertrand (1773 – 1844), Bonaparte’s companion in exile.

The charming fountain was located in the hollow of a valley, The Sane Valley, later named “Geranium Valley”. All calm and cool, it was a haven of peace, gentle and bucolic. He was buried here, his coffin placed in successive caskets, the first made of tin, the second of wood, the third of lead and the last of mahogany. The burial chamber housing the coffin was built like a fortress. Excavated to a great depth, bricked and paved, the pit was designed to prevent desecration. A letter from Sir Hudson Lowe, Governor of the island, to Lord Bathurst, Minister of War and the Colonies, describes in detail the precautions taken:

A large pit was dug of sufficient width all around, to admit a two-foot-thick wall of solid masonry, being built on either side; thus, forming an exact oblong, hollow space within which was precisely twelve feet deep – nearly eight long and five wide. A masonry bed was at the bottom. On this foundation, supported by 8 square stones each a foot high, lay a slab of white stone five inches thick; four other slabs of the same thickness closed the sides and ends, which, joined at the corners by Roman cement, formed a kind of stone tomb or sarcophagus. It was just deep enough to admit that the coffin had been placed there. Another large slab of white stone, supported on one side by two pulleys, was placed on top of the tomb, after the coffin had been placed there, and each interstice then filled with stone and Roman cement. Above the slab of white stone which formed the lid of the tomb, two layers of masonry, strongly cemented, and even clamped together, were constructed, so as to unite with the two-foot wall which supported the earth on either side, and the empty space between this latter work of masonry and the surface of the ground, measuring about eight feet in depth, was then filled with earth. The whole was then covered a little above ground level, with another bed of flat stones, the outer surface of which extending to the edge of the two-foot wall on either side of the tomb, covers a space twelve feet long and nine feet wide.

British Library Mss Add 20133 Fol 200 r.v

The plaque fixed to the coffin, which was usually engraved with the identity of the deceased, remained silent. The English and French could not agree on the “right” name to be given. On St. Helena, everyone still had vivid memories of the actions of the man who had shaken Europe. But was the same true on the Old Continent?

"Napoleon is no more! the journey of a historic short story

In the first half of the 19th century, media hype was still a thing of the past, thanks to the instantaneous, globalized relay of information. So, when Napoleon died, letters had to be written, ships had to be sailed, crews had to be mobilized and currents and winds had to be favorable in order to reach Europe in record time. It took an average of just two months to set foot on English soil after leaving St. Helena.

On the evening of May 7, the HMS Heron set sail for England with Captain Crokart, Napoleon’s witness before and after his death. The Marquis de Montchenu (1757-1831) should have been on board, had not Talleyrand, “the most boring man in the world”, stupidly missed the departure, already dozing off in his bed.

Bonaparte would certainly have seen it as yet another reason to rage against this “old fart” (sic), a point that the Count of Balmain, the Czar’s commissar on St. Helena, agreed with, stating that “what’s annoying is that the portrait looks just like it.

Montchenu set sail two weeks later aboard HMS Rosario, but by chance arrived in Portsmouth on the same day as HMS Heron, July 3, almost two months after Napoleon’s death. Two months during which the world, with the exception of a tiny island lost in the Atlantic, ignored the death of the “great man”, as Lord Byron put it.

Napoleon's death: a financial windfall

While Bonaparte’s companions in exile no doubt imagined a thunderous reception when the terrible news was announced, it would be an understatement to say that reactions were lukewarm. In England, London was preparing for the coronation of George IV. The news arrived on July 4 and spread rapidly. It seems that the Star was the first to announce the death of the enemy. While the front page of the paper featured a kaleidoscope of tantalizing advertisements, an addendum entitled Evening Star announced in capital letters the Death of Napoleon. The paper was closely followed by the Statesman, the second daily to publish the startling news.

Naturally, George IV had been informed of this news in the morning, but the testimony of this announcement, reported in her Memoirs by the Comtesse de Boigne, gives a fairly clear idea of the place Napoleon occupied in the mind of the sovereign, who was preoccupied at the time with other equally dangerous and daily threats:

Lord Castlereagh, on entering George IV’s study, said to him:

“Sire, I have come to inform Your Majesty that She has lost Her most mortal enemy. Why,” he cried, “is it possible! She is dead!”

Lord Castlereagh had to calm the monarch’s joy by explaining that it was not the Queen, his wife, but Bonaparte. A few months later, the King’s hopes were fulfilled.

Récits d’une tante: mémoires de la comtesse de Boigne, née d’Osmond T.3, chapter V

What the British took from this historic news on the eve of the royal coronation was above all the salutary break in the expensive upkeep required to guard Napoleon on St. Helena. No less than £400,000 could now be used for something other than guarding a deposed emperor. Since France had no such savings to look forward to, did the grief and sorrow caused by Napoleon’s demise outweigh the pragmatism?

Have we forgotten Napoleon?

Without having quite forgotten him, his name seems to ring, six years after his departure for exile, like that of a tyrannical old uncle who should have been sent to a retirement home. Unexpectedly, the news of Bonaparte’s death did not go down well in French society, which was not at its best. King Louis XVIII, a podiatrist and almost infirm, was living out his final years. His nephew and heir had unwillingly passed to the left, assassinated on February 14, 1820 by a Bonapartist worker. On July 5, the news of Napoleon’s death finally reached the king’s ears, but he was not as outspoken in his joy as might have been expected, and as the Ultras (royalists hoping for a complete return to the Ancien Régime) would certainly have wished. Those in the palace who had known and appreciated the deposed emperor – and there were many of them – were therefore not rebuffed with a few discreet sighs.

Newspapers are similarly cautious, but in any case, the news doesn’t seem to be upsetting the French. Was it the surprise effect, a lapse of memory or a lack of interest that left society indifferent? Contrary to what was asserted a few decades later, grief and tears did not suffocate the people that year. Indeed, this is what astonished those who witnessed this historic event. The Countess de Boigne, for example, could not believe her eyes:

While revolutionary passions were stirring in Europe, the powerful hand that had tamed them and made them serve to spread his name throughout the universe, this unarmed hand that still frightened nations, was yielding to the most terrible of conquerors.

On May 5 1821, Napoleon Bonaparte breathed his last on a rock in the middle of the Atlantic. Destiny had thus prepared the most poetic of tombs for him. Placed at the end of both worlds, and belonging only to the name of Bonaparte, Saint Helena became the colossal mausoleum of this colossal glory; but the era of his posthumous popularity had not yet begun for France.

I’ve heard street hawkers shout: “Napoleon Bonaparte’s death, for two sols; his speech to General Bertrand, for two dols; Madame Bertrand’s despair, for two sols, for two sols”, without it having any more effect on the streets than the announcement of a lost dog. I still remember how struck we were, a few slightly more reflective people, by this singular indifference; how often we repeated: “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity!” And yet glory is something, for it has regained its level, and centuries of admiration will avenge the emperor Napoleon for this moment of oblivion.

Récits d’une tante: mémoires de la comtesse de Boigne, née d’Osmond T.3, chapter V

Death of a man, birth of a myth

The Countess was right, and a decade later, spirits were beginning to flare. The Napoleonic myth was on the march: people began to wonder about the supposed cruelty of Napoleon’s jailers or his possible poisoning, and the Petit Caporal became a romantic figure in 19th-century literature. “What a novel my life is”, Napoleon who had himself sketched out the broad outlines of his myth was, after his death, recounted by the greatest. Chateaubriand, Balzac, Zola, Michelet and Stendhal all contributed to mythologizing this historical figure, who is still shrouded in legend today.

Victor Hugo, excerpt from Buonaparte, poem composed in March 1822 and published in the collection Odes et ballades (1826):

There, cooling like a torrent of lava,

Guarded by his vanquished, driven from the universe,

This remnant of a tyrant, waking a slave,

Had only changed irons.

Restored thrones listening to the fanfare,

It shone like a lighthouse from afar,

Showing the reef to the boatman.

He died. – When this noise broke out in our cities,

The world breathed in civil fury,

Delivered from his prisoner.

Why was Napoleon exiled to St. Helena?

The mere mention of his name sends shivers down the spines of Europe's greatest men. So when Napoleon surrendered to his enemies, the Allies wanted only one thing: to get rid of the ogre once and for all.

The beginning of the end: Waterloo

It is said that Napoleon was to remain an islander. Born in Corsica, the emperor was exiled after his first abdication in 1814 to the island of Elba, off the Italian coast. He was almost sent to St. Helena in 1815, as Elba was rightly criticized for its lack of security. Ironically, the British government refused the move, which only delayed the deadline for Napoleon’s last cruise.

Certainly, the island of Elba lacked the height to keep the little corporal from sneaking out. Leaving the tiny kingdom he had been granted after three hundred days, he returned to the mainland and set off for the Flight of the Eagle, initiating the Hundred Days (which counted his time back in power), ousting Louis XVIII before being defeated on June 18, 1815 at Waterloo by the hastily and successfully reformed Allied coalition.

After this crushing defeat, Napoleon managed to leave the battlefield and began his escape. He first headed for Paris, where he hoped to play a political role, but failed. He then took the road to Malmaison, giving Joseph Fouché, then head of the provisional government, enough time to betray him by reporting the deposed Emperor’s plans to the Allies already on his tail. Napoleon’s plans were now known: to reach Rochefort and set sail for America. The British fleet was immediately mobilized to block his escape. In the meantime, Louis XVIII’s policemen set off to catch up with the infernal fugitive.

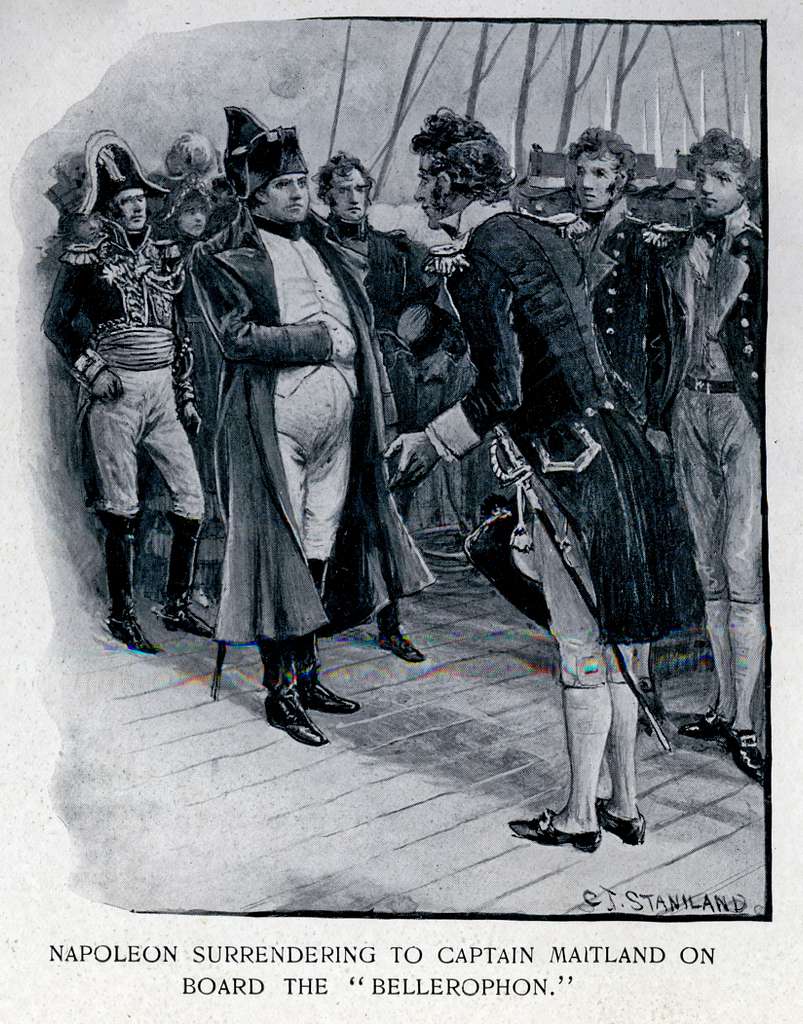

Napoleon now had two options: to escape by hiding in a fast boat, capable of escaping the English blockade, and placed at his disposal, or “to abandon himself to the generosity of the Regent of Great Britain”.

"Like Themistocles, I have come to sit at the hearth of the British people", Napoleon becomes an Anglophile

The game is afoot, and each protagonist has a card to play. Napoleon doesn’t speak a word of English, he doesn’t understand British culture, but he’s not unaware of Albion’s liberal right of asylum. At the same time, the British claim Napoleon as their deserved trophy. After more than twenty years of fighting him, they asserted their right to make him a prestigious prize of war. The Allies are not opposed to this demand, as long as Great Britain takes responsibility, at its own expense, for the prisoner’s upkeep and close, necessary surveillance. If the victorious coalition at Waterloo had its way, Bonaparte’s fate would have been sealed in a radical and expeditious manner, and at no extra cost.

Meanwhile, Napoleon refused to flee into hiding, like a common fugitive. All the more so as the legislation in force among his English enemies could work in his favor, and give him a chance to live out his days in peace. In any case, that’s what Cambacérès and other eminent jurists were betting on in the wake of the Belgian debacle.

So the Emperor played his last card and, as a show of (false?) good will, surrendered himself to the English forces by joining the Bellerophon, a ship anchored in Rochefort harbor, shortly after 6am on July 15, 1815.

I have come to place myself under the protection of your prince and your laws […] The fate of arms has brought me to my cruelest enemy, but I am counting on his loyalty.

The next day, the ship sails for England. Meanwhile, in London, we still don’t know what to do with this prestigious, but oh so cumbersome prisoner. Send him to prison in England? To Scotland? Suggestions of St. Helena, Malta and Gibraltar were once again on the table. The most important thing, it was thought, was to find the most remote and perfectly secure location. But Bonaparte’s popularity was not to be taken into account.

An unexpected welcome in Torquay harbour

The orders transmitted to the Bellerophon were very clear: Napoleon was not to leave the ship or set foot on British soil, as the law of the land would have to be applied to him. And given the welcome Bonaparte received once the ship reached the Devon coast, these precautions were not too much to ask!

As soon as the Bellerophon docked in Torquay harbor at dawn, news of its famous passenger spread like wildfire. Soon dozens, then hundreds, and by the next day nearly a thousand canoes loaded with curious onlookers were trying to catch a glimpse of the famous emperor. And, against all odds, British phlegm wins out over fear, anger or revenge. Canoeists greet Bonaparte in a friendly manner, women wave their handkerchiefs and others even throw him flowers!

On deck, Napoleon naturally found the welcome charming. Reassured by this joyful arrival, he took up his pen and addressed a letter to the future George IV (1762 – 1830). In this missive, which never reached the Prince Regent, Bonaparte showed his humility, announcing that he wished to “come and sit at the hearth of the British people”. In all simplicity, he asked the future sovereign for a small estate near London, where he and a few of his retinue could quietly end their days. It seems that Napoleon already saw himself as a gentleman farmer, happily observing the course of the world from his luxury cottage!

Having no doubt dreamed of making England part of his empire, it would be amusing if the enemy island were to become his land of asylum. But that doesn’t amuse some members of the British Parliament! If he stays too long in Torquay, this damned Frenchman will end up winning over popular fervor if we’re not careful! All the more so as it only takes one of his two feet treading Devon soil for him to be able to legally lodge a habeas corpus petition, which we fear will be honestly granted.

Habeas corpus and Napoleon's disillusionment

This was the pride and weakness of the English. The Magna Carta, drawn up in June 1215, established the respective rights of the king and the barons, as well as the Church and the towns, in the government of the kingdom. At the beginning of the 19th century, it was still in force (with a few exceptions, especially in Napoleonic times). Article 39 states that “No free man shall be arrested or imprisoned, or dispossessed of his property, or declared an outlaw, or exiled, or executed in any manner whatsoever, and we shall not act against him nor send anyone against him, without a lawful judgment of his peers and in accordance with the law of the land.”

In 1679, this text was supplemented by theHabeas Corpus Act guaranteeing individual liberty, in order to avoid arbitrary detention through judicial justification, by giving the detainee the right to appear immediately. This applied to anyone on British soil. Napoleon and his advisors believed that these laws would provide the deposed emperor with an honorable retirement. But he still had to put his foot down. And everything was done to ensure that never happened.

The island of St. Helena was chosen as Napoleon’s last place of residence. The fact that it was lost in the middle of the Atlantic, between Brazil and Angola, was already an advantage. Unlike Elba, Napoleon would be so far from any continent that to escape would be considered a complete absurdity. Added to this were reports by specially commissioned officers measuring the island’s advantages as a prison. Firstly, its small size meant that it could be defended with very few resources, especially as St. Helena was already bristling with English guns and only accessible via the port of St. James, the rest being steep, immense, sharp cliffs. Few people live here, and any stranger is immediately spotted. And, the icing on the cake, the island doesn’t belong to the British crown, but to the East India Company. The nuance is subtle, but legally precious, as it prevents Napoleon from falling under the authority of Magna Carta and habeas corpus. The terms of the detention were carefully drawn up by both parties, the government and the shipping company, so that the English were solely in charge of Napoleon’s detention. A special commissioner was appointed to represent the Russians, Prussians and Austrians.

Napoleon’s fate was sealed. He may not have set foot in England, but he is about to taste the delights of his empire. He may not have set foot in England, but he’s about to taste the delights of his Empire. Ironically, the English can say the same of his freshly collapsed empire.

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

How did Napoleon Bonaparte come to power?

18 Brumaire, Year VII: Napoleon Bonaparte orchestrates the slowest coup d'état in French history.

An emperor is neither made alone, nor in a day. His rise to prominence is based on iron will and hard work, luck and the ability to surround oneself with the right people.

Our young Corsican was in his early twenties when the Bastille was taken in July 1789. From that pivotal moment onwards, his career began in earnest. In September 1793, he was appointed captain at the siege of Toulon, and became a general in December. In 1796, he left for the Italian campaign. France was then a Republic, the first in its history. Scandalized by different periods, it opened with the National Convention – infamous for its episode of the Terror – from 1792 to 1795. A new constitution ushered in a new era: the Directoire, from 1795 to 1799. Under this regime, executive power was divided between five directors, heads of government who were regularly replaced, and ministers. Legislative power was entrusted to two assemblies: the Council of Elders – forerunner of the Senate – and the Council of Five Hundred (comparable to our National Assembly). This political system, designed to avoid tyranny, was based at the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris.

It was under the Directoire that Napoleon began his historic rise, taking advantage of the difficult context in which the government was mired. The political instability and violence that accompanied the Revolution went hand in hand with an exhausting battle against European coalitions directed against the French Republic, as well as a fierce struggle, within the country itself, against the Chouans, the royalist insurgents. The already deplorable economic situation did not improve. While the Directoire set about laying the foundations of a solid financial system, cleaning up finances and making direct taxes fairer, indirect taxes multiplied and increased considerably. Public opinion focused on forced requisitions and loans, constant fighting and trial and error. However, the foundations laid by the Directoire would serve the next regime, the Consulate, headed by Napoleon Bonaparte.

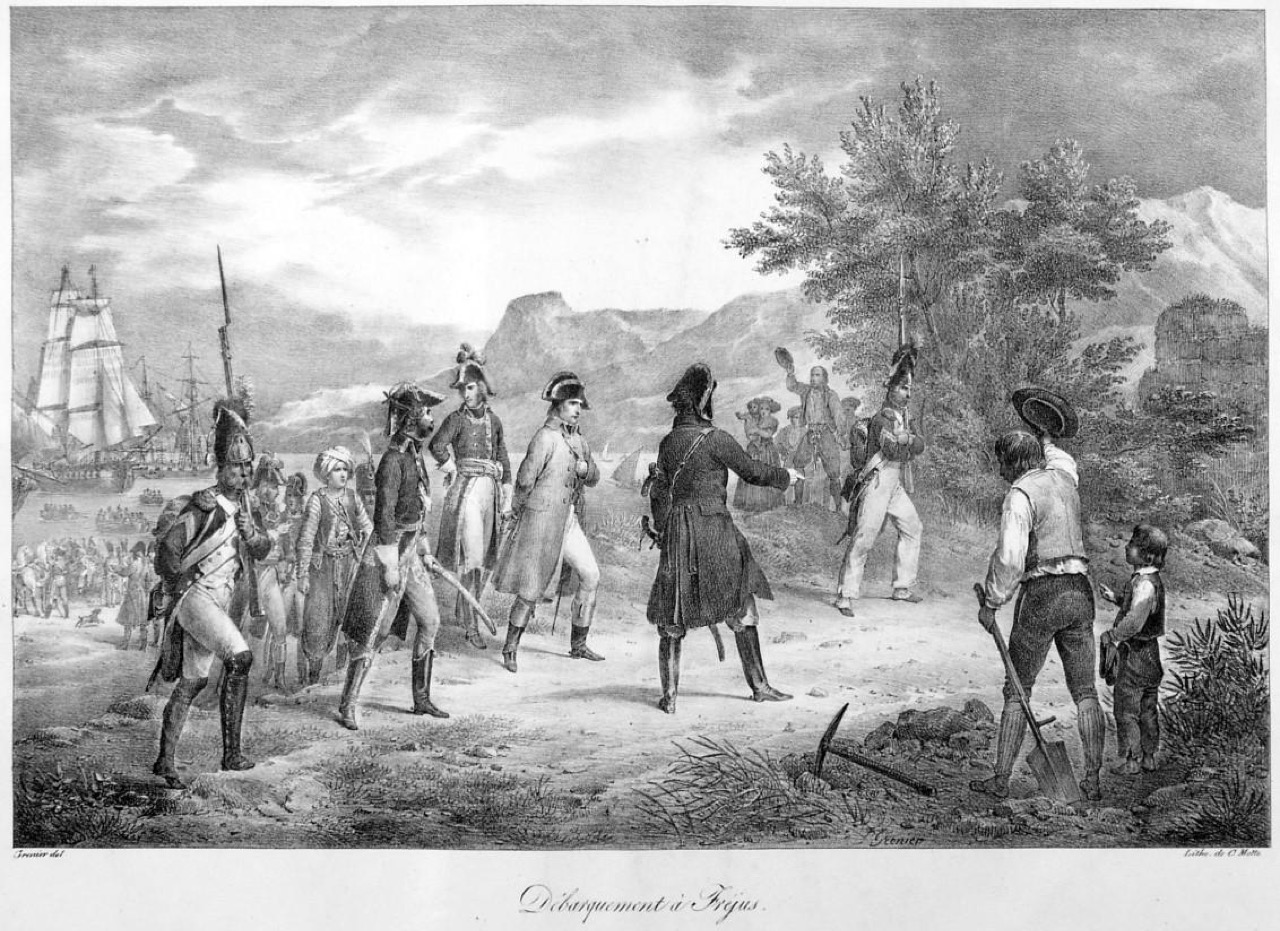

The deserter general: Napoleon from Egypt to Paris

It was recriminations against the Directoire and serious military setbacks on the German, Italian and Swiss fronts that created the opportunity Bonaparte was able to seize. Considered the hero of the Italian campaign, the successful general had been in Egypt since May 1798. In July, the Battle of the Pyramids cemented the general’s prestige, while Admiral Nelson sank his dreams of the Orient on August 1 in the bay of Aboukir: the French fleet was wiped out. More victories – and more defeats – lay ahead, until the victorious land battle of Aboukir on July 25, 1799.

At the end of the latter, news of the French political situation reached him, and it was far from cheerful. The Italian conquests he had so lavishly staged in his polished propaganda were lost, and others seemed on the verge of being lost. Well aware that his flattering reputation as a victorious, peacemaking general was still very much alive in France, carefully nurtured by his brother Lucien (deputy to the Conseil des Cinq-Cents), General Bonaparte decided to return to France, without having been ordered to do so. In short, he deserted, a tasteful choice that matched the North African landscape.

Surrounded by the British, he nevertheless managed to escape to England, taking with him Chief of Staff Louis-Alexandre Berthier, General Joachim Murat, Brigadier General Auguste-Frédéric Viesse de Marmont, Major General Jean Lannes and Battalion Chief and Brigadier Géraud-Christophe-Michel Duroc. Nor did he forget the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet and the great narrator of his adventures, the writer Dominique-Vivant Denon. This fine crew arrived in Fréjus on the evening of October 8, and Bonaparte and Berthier left immediately for Paris.

Triumphant return

In the meantime, the French military situation had recovered, but the Directoire is not in the odor of sanctity, and all that was needed was the surprise arrival of the general to add fuel to the fire. All the way to Paris, the deserter was hailed and welcomed as a savior (not to say a king). While his superiors should, at the very least, have raised their voices, the news of his dazzling victory at Aboukir reached Paris ahead of him and made the headlines. Bonaparte, who had grown impatient during the Mediterranean crossing, worried about arriving too late and missing his chance, could not have entered the capital under better auspices. He now appeared to public opinion as the providential man.

It was the first time since the Revolution that a proper name was heard in every mouth. Until then, it had been said that the National Constituent Assembly had done such and such a thing, that the people had done such and such a thing, that the Convention had done such and such a thing; now, all the talk was of this man who was to take the place of everyone else, and make the human race anonymous.

Madame de Staël, Considérations sur les principaux événements de la Révolution française, tome 2, 1817, p. 8.

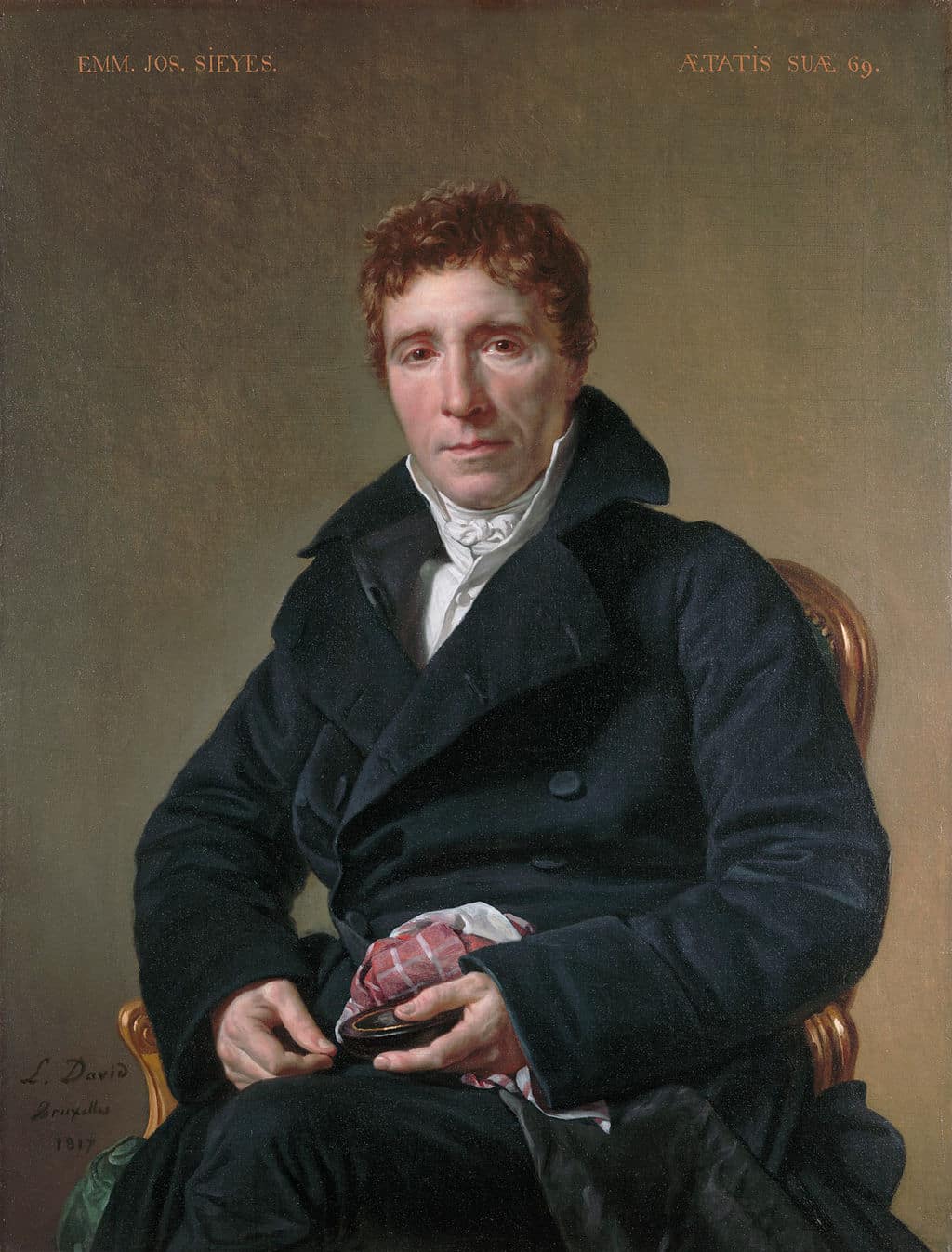

Preparing for the coup

Napoleon Bonaparte may have been acclaimed, but the clamor was not unanimous. What marks this triumphant return, however, are the votes he wins across the political spectrum. From royalists to Jacobins, he found supporters who saw in him what they wanted to see, because for the General, only one thing was clear: he had to keep his political intentions vague. If he now sees power within his grasp, he is perfectly aware that the only way to bring down the Directoire is to stage a coup d’état that would be supported by public opinion. The idea was to flout the people’s representative political authority with the people’s approval, in a kind of “civilian” coup d’état. To achieve this, he had to forge the necessary alliances without revealing them, suggesting to each side that he could be their ally. But most choices are quickly discarded. His former mentor Paul Barras, Director of the Republic, was too associated with previous regimes, and the Jacobins too unpopular. That left Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748 – 1836), known as Abbé Sieyès, a strong personality whose epidermal reactions to Bonaparte’s ego were easy to foresee.

However, Sieyès and Lucien Bonaparte had drafted a constitution during the summer, which played into Bonaparte’s “civil” ambition to seize power. Although the two men stared at each other, they knew each other to be useful, and it was thus that the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire brought them to power.

18 brumaire an VII, another name for November 9, 1799

If we retain the 18th, we should also take into account the 19th of Brumaire, as this coup d’état surprisingly took its time! It took two days to overthrow the Directoire. Coup” is perhaps the least appropriate word to describe this historic event, and “trap” would undoubtedly be preferable.

The removal of the current regime was organized in two stages. Firstly, on the 18th, the representative assemblies were moved from Paris to Saint-Cloud. To justify this exceptional (and legal) measure, the organizers of the coup argued that a plot to assassinate the deputies had just been uncovered. State representatives were to be moved away from Paris, isolated, so that their protection could be better assured by the military troops led by Bonaparte. On the 19th, at Saint-Cloud, the deputies were urged to vote for the change of regime, but some refused, guessing at the real reason for the military presence. Bonaparte intervened with a speech so clumsy and awkward that even his friend and supporter Louis Antoine Bourrienne (1769 – 1834) invited him to leave the room where the furious deputies were sitting.

The stormy negotiations dragged on for two days, and it was on the evening of the 19th that Lucien Bonaparte, presiding over the Conseil des Cinq-Cents, declared the chamber legally constituted. The following day, directorial power was entrusted to three provisional consuls: Bonaparte was the first and remained so, followed by Sieyès and Roger Ducos (1747 – 1816).

The Consulate was officially installed on January 1, 1800 (11 nivôse an VIII). It was headed by the First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte, the Second Consul Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès (1753 – 1824) and the Third Consul Charles-François Lebrun (1739 – 1824). These were three different political sensibilities with the ambition of restoring national cohesion and understanding. However, this new triumvirate was not to everyone’s taste, but that didn’t matter: for the years to come, Napoleon would be the one to reckon with.

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

Napoleon Bonaparte and Fort Boyard

Today the most famous French fort in the world brings together intrepid participants ready to brave tarantulas and enigmas to steal its treasure. However, long before distributing its wealth, the construction of the fort initiated by Napoleon cost quite a fortune to prove ... perfectly useless.

Fort Boyard, an impractical project

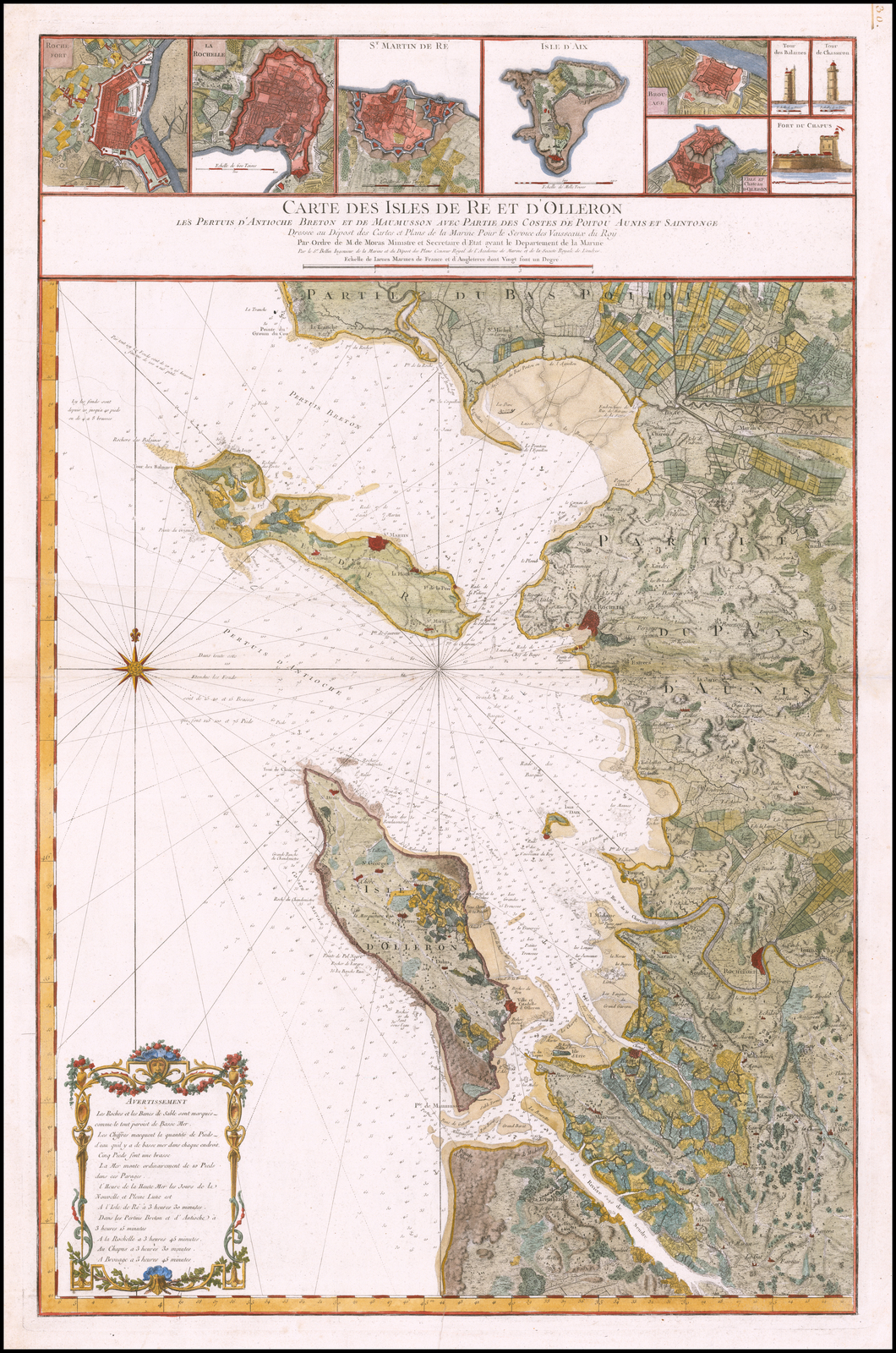

In 1666, Colbert convinced Louis XIV of the importance of building an arsenal in the Antioche strait, a maritime boulevard facilitating the entry of enemies onto the Charente coast. Rochefort emerges from the silts with a lot of royal liquidity so well that it is designated as the “golden city” raised in record time on the marshes. Impossible for this city to exist without its harbor. However, this roadstead located opposite the wide open Antioch strait can only count on a very modest avant-garde: the island of Aix . This tiny crescent of land three kilometers long and barely 600 meters in its greatest width is charged, almost by itself, with the guard of the whole arsenal. Its strategic importance is considerable and inversely proportional to its size!

Thus, from 1689, the island of Aix and the small Madame island at the opening of the estuary became the object of slow but absolutely necessary fortifications. Vauban fortified the village in 1669 and then at the beginning of the 18th century, the forefront Sainte Catherine, in the south of the island, was equipped with the Fort de la Rade, which did not resist an English attack in 1757. There is no doubt that the island of Aix is definitely a strategic high place and it is indeed the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte who takes full measure of this delicate situation.

From 1801, Bonaparte noticed the weakness of the fortifications and the poverty of the defense system. If by chance the English made a breakthrough in the Antioch strait, nothing could firmly stop them. This vulnerability must be remedied as quickly as possible! The First Consul therefore instructs the General Inspector of Maritime Works Ferregeau to take up the idea already expressed in the 18th century of a fort along Boyard’s loins. The project is ambitious because this rope is a sandbank located halfway between the island of Aix and the island of Oléron. Already spotted by Dutch sailors who are wary of it, this bench known under the name of “banjaert” in Dutch and “boyar” in Anjou and Saintonge gives the construction both sorrows and its name.

The project is ambitious, probably too much for the means at the time. It is necessary to build on this bench an artificial reef on which will sit the foundations of a building, gigantic elliptical ring 80 meters long and 40 meters wide. The fort is based on a new defense system theorized by Montalembert who offers instead of a bastioned fort, a frontal opposition to the enemy who must take advantage of the firepower of the powerful guns. It was by banking on this remarkable progress in artillery that he saw how to go beyond Vauban’s defense systems.

In 1803, work began with the construction of Boyardville, on the island of Oléron. Workshops and materials were set up there. On May 11, 1804, the first block of stone was laid, then followed by those taken with explosives on the point of Coudepont on the island of Aix and then transported in boats and barges along Boyard. The work is exhausting, difficult and accidents regularly punctuate the rise of the artificial island which finally emerges above the water and whose first crown wall is visible in 1805. It won’t be visible for long. The winter storm that same year reduced him to nothing.

Courageously, workers return to the task. The means were reinforced in 1805 and finally, the platform which will support the future fort is visible at low tide. The first seat rises. Unfortunately, the storms of winter 1806-1807 once again erode all the efforts made for several years. The blocks so difficult to transport sink to the bottom of the sea, nothing remains of the first course placed on Boyard’s sandbank. This pharaonic project mobilizing very large sums of money is in the headlines: should the country persist in pursuing such a project in such difficult conditions? The works were immediately suspended and the local authorities await the visit of Napoleon I in the summer of 1807. He alone will be able to decide on the future of the fort. The emperor, convinced that this building would finally allow effective defense of the Antioch strait, ordered the work to continue… but in reduced dimensions: 68 meters in length, 21 meters in width and 20 meters in height at the ramparts. The walls should be more than two meters thick. Painfully, the construction site resumes.

Impatient, Napoleon I wanted results, and quickly. Since the garrison of the island of Aix and the mobilized workers were not enough, the emperor was determined to draw on the resources of a population that could be forced into labor, that of convicts from reformatories and a few prisoners of war. The construction workforce now stands at 27 ships, 186 crew members and at least 600 workers. Alas, the imperial will, however firm it may be, can do nothing against damage. A new foundation is put in place. It is feared that it will sink under its own weight which is greatly reduced. The joints are made with lime and the blocks are firmly anchored to each other by “strong iron spikes”. But, definitely, winters are not favorable and that of 1808 is no exception: the storm is raging, the base is sinking again while the wages of the workers are too sporadic to give them the heart to the work. Another year of laborious efforts punctuated by mutiny and the battle of the fireships will put an end to this expensive project for a few years.

The Battle of the Basque Roads, April 1809

From April 1, a frigate and an English brig – undoubtedly under the guise of English humor – interrupt the work on Boyard’s sandbank and scrupulously destroy the installations without worrying about the crossfire coming from the island of Aix and Boyardville. Ten days later, an explosion resounded in such a deafening crash that it was said to have been heard as far as Poitiers. The English threw frieships into the sea, old and unusable ships transformed into infernal machines because they were loaded with explosives of all kinds. Navigating with the currents, these time bombs are heading straight for the fleet of the admiral Allemand who has no other choice but to deal with the most urgent, striving to save his crews and ships from disastrous fires. The result is disastrous. Certainly, several sailors and ships were saved, but there was hardly anything left of the fort under construction. The project was abandoned and would not be relaunched until 1842.

The efforts to be deployed are just as colossal as at the beginning of the 19th century but no longer take into account the progress of artillery. And when Fort Boyard is finally completed, the result is a perfectly useless building that neither artillery nor strategy needs. Abandoned for years, it eventually became a military prison but closed again in 1913. It will have to wait until the end of the 20th century to become the celebrity we know today!

Fort Boyard and the Fortified Belt of the Antioch Strait

The Fort Boyard project was to reinforce a defense imagined to defend the bay of Rochefort and the access to the strait of Antioch. This fortified belt with impressive cross-fire power was to pass the envy of any enemy to venture further in his project. To do this, Napoleon I started the construction in 1808 of Fort de la Sommité on the highest point, north-east of the island of Aix. The bastion was renamed Fort Liédot in 1812 in homage to Colonel and military engineer François Joseph Didier Liédot (1773 – 1812), who died during the Russian campaign . It took 24 years for Fort Liédot to be completed, but its construction was remarkable in many ways. All in Crazannes stones, the fort is built on a bastioned square plan and equipped with a model tower n ° 1 type 1811, a standardized defense construction bringing together in a single building the gunpowder magazines, the food stores and the housing of the gunners. After some modifications, this model will become a redoubt-model n ° 1, the one and only copy built of this model. The whole could shelter a garrison of 600 men or… children. It is in fact the future that was finally reserved for this fort which became a place of detention before being transformed into a reception structure for summer camps. Some will see it as a link that we will not substantiate.

Instead of the fort destroyed by the English at Sainte Catherine Point in the 18th century, it was decided to take back what was left of the old construction and to build a fort regularly modernized throughout the 19th century.

A stone’s throw from the Ile d’Aix at the mouth of the Charente and accessible on foot from Fouras, the rock of Énet, accessible at low tide, had already shown its importance, evidenced by its fortification from the Middle Ages. After the Battle of the Basque Roads in April 1809, the construction project for Fort Énet was put back on the table. Its main interest lay in the possibility of crossing the fires of Énet with those of Coudepont on the island of Aix, more solidly protecting the access to the bay of Rochefort. Today, Fort Énet is admired less for its crossfire than for its elegant architectural simplicity, much appreciated by connoisseurs and lovers of fortified structures.

Despite all his will and the awareness he had of the weakness of the maritime defenses of this part of the Atlantic coast, Napoleon I never succeeded in setting up the fortified belt he had imagined to defend the Antioch strait. Ironically, the island of Aix was as much the core of a defense strategy against the English as the last stay of the emperor before surrendering to them. He was then preparing to join an island whose remoteness was the best bastion against any attempt at attack .

Napoleon and the Numbering of the Streets

Napoleon Bonaparte regularly demonstrated a very modern pragmatism. If our daily life owes him a lot, from the baccalaureate to garbage collection, let us recognize him for having succeeded in enforcing the numbering of buildings and houses, a challenge which exhausted the resources of many of his predecessors.

Numbering the Streets: a Long-Standing Initiative

If the numbering of streets as we know it today is quite recent, the idea is nevertheless old. In 1421 in Paris, the newly rebuilt Notre-Dame bridge, made of wood on stone piles, has no less than sixty houses which will savour against their will the water of the Seine during the destructive flood of 1499. On this bridge, the dwellings are numbered in Roman numerals and are the only ones to benefit from this treatment in the city. Once at the bottom of the river, these houses will be the only memory of a numerical experience that will not be repeated for several centuries. While waiting for the Age of Enlightenment, one orients himself in the cities by following approximate itineraries articulated on landmarks that are the signs of the houses or the specificities of the district. Failing to find his way quickly, the pedestrian can at least savor the poetry of picturesque mazes with names inherited from some curious legend. So it is with the rue du Chat-qui-Pêche as well as that of the Puits-de-l’Ermite or the rue Perdue.

In the eighteenth century, especially in its second half, it seems that the taste for clarity and simpler travel directions take over and house numbering becomes common in many cities. The exercise is most often used to better collect taxes or to accommodate more easily the troops of passing or occupying armies. But the foreign visitor or the lost provincial undoubtedly enjoys – even before the inhabitants – the comfort of strolling in an unknown city without fear of getting lost because the sign serving as a landmark closed without anyone being informed. Thus the numbering of dwellings appears for example in Prussia in 1737, in Madrid in 1750, in Milan in 1786 and in Paris in 1779. Vain undertaking in the French capital because it is an understatement to specify that Parisians are reluctant to face this initiative. As you number the day, the fresh paint indications disappear at night! At a time when rumors – and the facts! – are going well and recognize in the marking of houses an indisputable sign of the imminent passage of thieves, no one is comfortable with the idea of a clearly visible numbering even though it would be generalized to all homes and without distinction of neighborhoods or social rank.

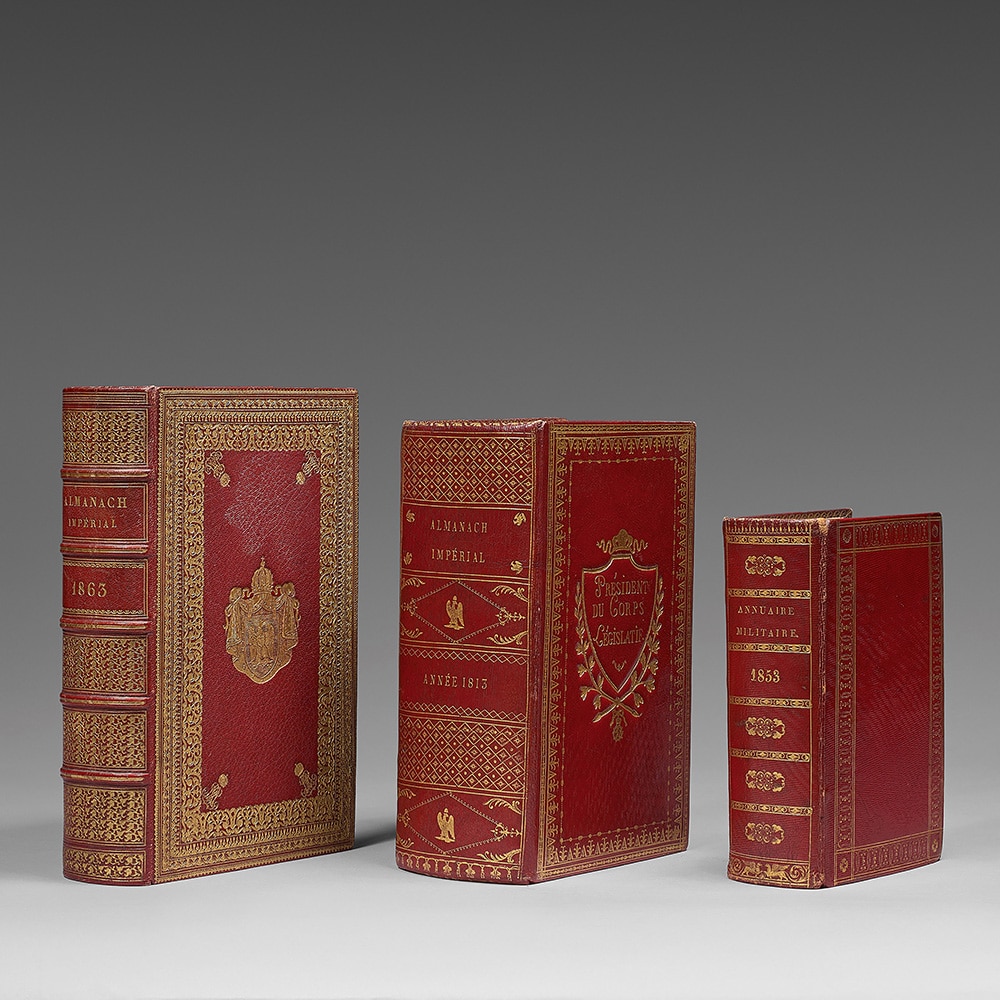

Yet the idea is gaining ground and the editors of almanacs and directories are not for nothing! It is easy to imagine the interest that such a numbering would be for them: addresses which would become precise and would need to be regularly updated so that the annual edition of almanacs and directories would turn into a particularly fruitful juicy affair. Moreover, it was on the initiative of one of these traders that the first Parisian numbering took place in 1799 and which ended in pitiful failure.

The Revolution, however, was not afraid to get to grips with the problem and concocted a system of such complexity that it was the source of particularly remarkable absurdities (numbers without continuation or the same number repeated several times in same street) and which miraculously made the system without numbering much clearer and simpler than the system being provided with numbers. All the same, Choderlos de Laclos (1741 – 1803), if he proposed a numbering system as twisted as the mind of the Vicomte de Valmont, imagined some ingenious systems such as that consisting in distributing even numbers to the streets perpendicular to the Seine and the odd numbers on the streets that ran parallel to it. If this is not quite the system set up by Napoleon I, we can recognize that he was inspired by it.

The Imperial Street Numbering System

On February 4th, 1805, a decree made street numbering compulsory. In Paris, the prefect Nicolas Frochot (1761 – 1828) is in charge of the application of this decree which is based on a system whose design was not a piece of cake!

Finally, the result makes it possible to see more clearly without creating complexities that are too crippling on a daily basis. Contrary to what Marin Kreenfelt de Storck, editor of the Almanac de Paris in 1779, advocated, the digital unit is now the house and no longer the door.

Then the numbering of the doors follows simple geographical rules capable of being applied to almost all the streets of the capital. A distinction is made between even numbers (to the pedestrian’s right) and odd numbers (to his left); the direction of the streets is oriented from upstream to downstream for streets parallel to the Seine, and from the banks to the north and south for streets oblique or perpendicular to the Seine.

Visually, the numbers are differentiated so as to facilitate understanding of the geographical position in which the pedestrian is. In the streets perpendicular or oblique to the river, the numbering is drawn in black on an ocher background while in the streets parallel to the Seine, the number is written in red, always on an ocher background.

The municipality of Paris took charge between June and September 1805 of the first numbering of the streets of the city but the maintenance of these numbers – so that they remain clearly visible – fell to the owners who one imagines that they were particularly enchanted by this new measure. Painting did not last long in the Parisian climate and the local authority published then generously a specification (height, location, color and material of the plate which could be glazed sheet, enamelled earthenware) leaving the owners the choice to invest in a numbering that did not require regular maintenance .

On June 28th, 1847, the application of the decree of the Prefect of the Seine initiated a regularization of street signs and numbering by opting for enameled porcelain plaques whose white numbers were inscribed on an azure blue background always currents in Paris and in the provinces.

When the new numbering system was applied, the problem of the Cité and Saint-Louis islands arose. Since the perpendicular streets as well as the parallel streets overlooked the Seine, it was decided to assimilate the Île de la Cité to the left bank while the Île Saint-Louis was similar to the right bank. By superstition, the number 13 of certain streets was replaced by the number 11 bis and sometimes, without any reason, streets were numbered backwards.

This decree of Napoleon I changed the way of conceiving the geographical space of a city. By facilitating all kinds of procedures, street numbering still makes it possible to move around quickly, without wasting time. Ironically, few streets named after Bonaparte allow the decree of February 1805 to be linked to its instigator. Rue Bonaparte in the 6th arrondissement of Paris evokes more the memory of the general than that of the emperor, while the quai Napoleon from 1804 is now divided into two parts, one called Quai aux Fleurs and the other Quai de la Corse, a modest evocation.

His native island and the island of Aix, the last one he trod before his rock of Sainte-Hélène, still have Napoleon streets like a few other French towns. In the absence of streets, let us remember the success of their numbering!

False Napoleon: Story of Madmen

The cliché is worn out. However, and as often, the stereotype settles on fertile and well-documented soil. Did the madmen taking themselves for Napoleon I really populate the insane asylums? Were they all mad or did they take advantage of a historic moment of confusion following Bonaparte's exile?

From the Revolution to the end of the Empire, in the throes of instability and violence

The adoption of the guillotine, recommended by Mr. Guillotin to establish equality between citizens even in the execution of the capital punishment, had consequences as incisive in the flesh as in the minds. So when on January 21st, 1793, Louis XVI was beheaded under the heartbroken eyes of Philippe Pinel (1745 – 1826), precursor of psychiatry in France, the doctor denied being a royalist but felt that if this troubled period literally caused the loss of their head for many citizens, others also lose it in a much more insidious way.

Terror not only threatens bodies, it also threatens minds. Because the daily lists of the condemned maintain, during weeks sometimes, a fear leaving no rest to the citizens likely to be led to the scaffold. Some minds do not resist such torture and sink into madness: “delirium, the subject’s bulwark against its own collapse has a lot to tell us about political violence” underlines Laure Murat, historian and author of The man who thought he was Napoleon.

The Empire does not put an end to the violence and uncertainty that are the daily life on the eve of the 19th century. The parenthesis is far from enchanted and it is almost a whole century which bears the stigmata of the Revolution. From 1789 to 1871, political regimes followed one after the other, without sustainability but always accompanied by political and social violence. The disturbances not only agitate the upper echelons, they are also expressed in the streets. How to endure such instability on a daily basis? The contemporaries of the time know too well that a political opinion for a time unanimous – and sometimes even rewarded – can turn just as quickly into condemnation at best social, at worst, to death. There is enough to lose your head there without having recourse to the terrifying “Louisette”, affectionate nickname of the guillotine in homage to one of its designers, the doctor Antoine Louis (1723 – 1792). Nevertheless, shady perspectives are opening up to the most solid … and the most disturbed minds?

Identity Theft: the Fake Napoleon I

The Restoration of 1815 is accompanied by an epidermal reaction of Louis XVIII confronted with the memories of the Empire. It is essential for the royalists to overwhelm the Napoleonic legend with all evils because the suppression of all its memories will not be enough to silence the Bonapartists. Everywhere in France, the portraits of Napoleon I, of the imperial family, the emblems and all the representations directly or indirectly touching Bonaparte are systematically destroyed, erased, scratched. The royalists’ solution is ultimately worse than the evil they are striving to boast about. Not only a trade in commemorative objects is set up (the tastiest of which is undoubtedly that of the waffle molds decorated with the imperial profile) but especially since the booksellers and hawkers are no longer authorized to disseminate the image of the general Corsican, impostors will have full latitude to play on the memory of a vague resemblance between their physiognomy and that of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Thus begins the short adventure of Jean Charnay, a former soldier in his thirties converted into a very curious activity of “teacher and peddler” that a woman recognizes in June 1817 as the fallen emperor. Poor and hungry, he does not particularly want to contradict this woman who does not budge: his face is identical to the profile of the old coins bearing the effigy of Napoleon I! It is well worth a good meal, the usurper does not deny… Charnay takes to the game of confabulation and seems convincing enough to get free food; he sometimes even obtains up to the totality of the savings of a few subjugated inhabitants. However, he does not keep everything to himself, the man is intelligent. He is keen to keep his rank because this is also the usurpation that fills his stomach daily. So here he is distributing money to the poor, a perfect disguise for the one who was still a destitute just a few weeks before. Because the masquerade lasts two months and takes the paths of Ain and Saône-et-Loire until Charnay-Napoléon was arrested on August 4 of the same summer 1817 and then imprisoned.

A previous usurper had been less successful in 1815, still in Ain, he only held out for two days. Jean-Baptiste Ravier, a former sergeant-major of the Grande Armée, also in his thirties, did not take much advantage of his imperial status before being imprisoned. We will not fail to raise the common point which unites these two characters as well in their misfortune as in the means which they employed to remedy it. Both were elders of the Grand Army. However, we know the unfortunate fate of many Grognards after the fall of the Empire. It was necessary to eat well and the confusion following the surrender of Napoleon Bonaparte was conducive to plant seed of doubt in people’s minds.

All the more so as Napoleon was not at his first coup and mastered like no one else the art of returns as dazzling as they were unexpected. The population was therefore legitimately entitled to doubt the emperor’s defeat and his exile when these characters appeared, claiming to be Napoleon I. Very clever the one who could accuse the credulity of the inhabitants of the provinces in such troubled times. On the other hand, these funny anecdotes are revealing of the powerful memory which Bonaparte left in the spirits, everywhere on the territory: no need for a perfect resemblance nor even to be of the same age as the Corsican; the evocation, the talent of orator and the bearing are often enough.

The memory of the great man is not always suggested by the impostor and recognized by the admirer. Sometimes a grain of madness comes to stop the machine and the false Napoleon is not only motivated by poverty. The example of Brother Hilarion – whose real name is Joseph-Xavier Tissot (1780-1864) – is edifying.

We are in 1823 and Napoleon Bonaparte died in Saint Helena for two years already. In 1822, Brother Hilarion, an unknown – for the moment relatively discreet – acquired a small castle in Lozère which he intended to welcome the needy and the weak of mind. No fees are charged for these patients or their families. Brother Hilarion and the few religious who accompany him take care of them and, unlike the unhealthy asylums which are the ordinary of unhappy disturbed patients, the Lozère establishment is a remarkable example of care and good treatment.

Now, Brother Hilarion is not just a Good Samaritan. His disturbing resemblance to the emperor, his charisma and his ease as a speaker disturb many inhabitants of the region who report to anyone who wants to hear them that Bonaparte is well and truly alive! He is only concealed under the monastic costume, undoubtedly to recover a peaceful life far from the risks of politics. The information is so convincing that it ends up arousing the interest of the sub-prefect Armand Marquiset. If Napoleon is back despite his announced death, Marquiset should be sure of it; this man would be quite capable of coming back from the dead!

Marquiset is quickly reassured. While he recognizes that Brother Hilarion expresses admirably and possesses the regular features reminiscent of those of Bonaparte, the sub-prefect also notes that the resurrected Napoleon sometimes seems “more disturbed than his patients”. Brother Hilarion will open several hospices and will strive to protect the weak of spirits or the insane. Despite a notoriety that will extend to several neighboring regions, Joseph-Xavier Tissot will have to give up his hospices for lack of means. Today, he is considered by some to be the forerunner of alienists, or at least an advocate of worthy psychiatric care, at a time when the idea was only just beginning to be heard.

The madmen who thought they were Napoleon: an evil that does not spare celebrities

The exile of Napoleon Bonaparte only reinforces the fascination for this character to whom nothing and no one could resist. Subjecting a large part of the European sovereigns only to his strength of character, his intelligence and his military and strategic genius above all, Bonaparte knew how to emancipate himself from the need for an aristocratic and historical ancestry to rise from a poor island nobility to the rank of emperor reigning over territories beyond the natural borders of France. Fallen for the first time, returned in a masterful tour de force and without any recourse to violence, Bonaparte is the perfect embodiment of Nietzsche’s Übermensch: freed from dynastic legitimacy, from the moral common to men and from social control. Napoleon Bonaparte is a self-made man , a charismatic and fascinating personality who inaugurates a new era where individualism is increasingly valued and encouraged.

In the troubled context of the 19th century, extraordinary historical figures are a solid anchor for those who lose their minds. Bonaparte, invulnerable and pugnacious, thus becomes a personality easily endorsed by the insane. Especially since the costume requires little investment: a frock coat, a bicorn hat and voila!

Thus, after the return of the ashes of Napoleon I in December 1840, Doctor Auguste Voisin saw about fifteen emperors enter the asylum of Bicêtre. And that does not go easy! Because like their model, each emperor is angry, capricious and authoritarian. Not supporting the contradiction, the meetings between two imperial personalities lead to inevitable fights where each one claims his legitimacy to the throne and accuses the rival of shameless imposture …

These madmen, convinced of being Napoleon I, are the occasion for Étienne Esquirol (1772 – 1840), a pupil of Voisin, to study and describe in detail this newly appeared disorder and baptized proud (or ambitious) monomania, of which the main characteristic lies in the astonishing consistency of the patients. The latter in fact retain all their intellectual capacities and their common sense, except of course their delirium of identity.

Yet it would be wrong to believe that Napoleon has a monopoly on monomaniac delirium. Although he wins with flying colours, he is battling it out with other prestigious competitors. Laure Murat thus identifies several notable personalities pleasing delusional patients: Louis XVI, Jesus or Mahomet are the most common. What do they have in common? They are out of the ordinary. Living a unique, extraordinary destiny, they extricate themselves from reality. Moreover, the insane are less raving about the person incarnate than about his title or the idea that one has of this person. Rather than embodying Napoleon Bonaparte, the madman embraces the personality of an emperor of unsuspected power.

Should we be surprised that Nietzsche (1844 – 1900), at the dawn of the delirium which will lose him in 1900, took a brief moment himself for Napoleon? In the same vein, the philosopher Auguste Comte (1798 – 1857) had already shown several signs of madness, as when leaving asylum, he signed the name of “Brutus Bonaparte Comte” in the register. Bad times for philosophers!

More recently, legend has it that the actor Albert Dieudonné (1889 – 1976), who played Napoleon for the eponymous film by Abel Gance (1889 – 1981) in 1927, was buried in the Bonaparte costume he wore on the filming. Whatever the reality, many of his colleagues at the time conceded that the actor narrowly escaped madness. Better! The director himself devoured by the personality of the emperor found himself psychic correspondences with the deceased emperor …

Even today, the stereotypical image of the madman invariably represents a man hand in the jacket, head held high and looking intractable. Napoleon Bonaparte, an icon as popular as his insane ersatz, never ceases to inspire… even the boards imagined by Hergé!

Napoleon Bonaparte in the Garden

In Saint Helena, Napoleon Bonaparte led a new campaign less military and more about gardening. In 1819, the surroundings of the house of Longwood were enriched with gardens designed and implemented by the Emperor himself. Did the memories of Joséphine's horticultural talents help the Corsican general to win this battle? No doubt, but with less grace than the famous French elegant...

Longwood Gardens in Saint Helena

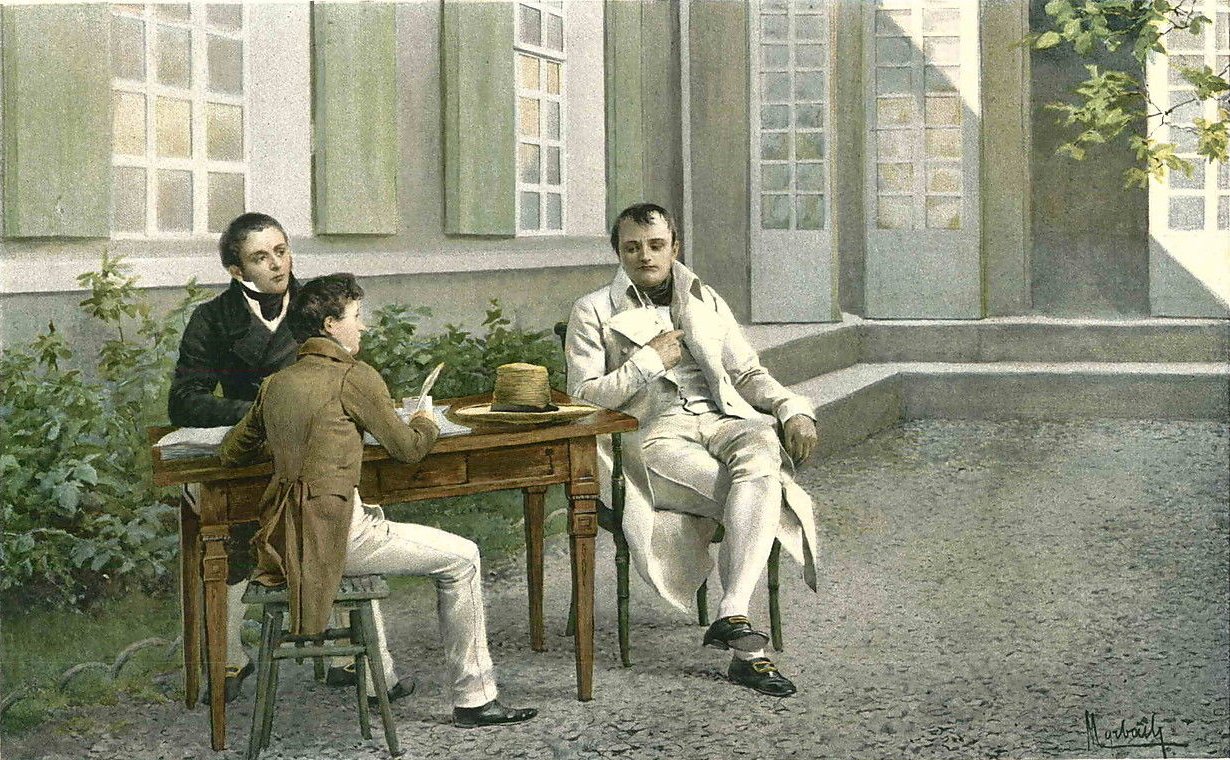

After five years of exile, the daily rhythm of Napoleon Bonaparte and his little court has slowed down and no longer has the imperial rigor of its beginnings. However…

We are at work from 5 am, and you would laugh heartily to see the Emperor spade in hand.

wrote Count Charles-Tristan de Montholon (1783 – 1853) in 1819.

Because at the beginning of the year, Napoleon resolved to follow (for once) a prescription from his doctors who recommended that he exercise. He could have been content with a daily walk but this kind of activity certainly lacks ambition. Redesign the gardens of his Longwood home, that has more scope! Never in doing things by half, the Corsican therefore undertakes a new gardening career. Two French gardens had already been designed when he arrived in 1815. But in 1819, Napoleon directed himself and with a rod of iron important works of which he drew the plans. And as in the past in the campaigns, he shared the daily life of his soldiers, he was the first to seize a spade or a rake, giving his companions in exile the example of work.

First of all, the new arrangements are intended to provide some shade in the gardens where Napoleon likes to lunch and entertain. A little shade and some plant ramparts against the trade winds soon enabled him to enjoy the outdoors more and to soften his exile. The Count de Montholon, again, testifies in February 1819:

In a few days, he thus succeeded in making us erect, in tufts of bad grass, two circular walls, eleven to twelve feet in height and a diameter of ten toises, as an extension of his bedroom and the library. Sir Hudson Lowe saw there at first only shelter from the wind, and did not object. […] This work done, the Emperor bought twenty-four large trees. He had them dug up with a clod of earth of a cubic height. The artillery agreed to have them transported to Longwood with the help of several hundred Chinese. The Emperor himself directed their plantation in the aisle after the library. […] The garden of the library was enclosed at the height of the steps of the topographical cabinet, or billiard table, as one will call it, by a semi-circular construction in tuff of grass and with steps; each row of steps was planted with rosebushes. […] A semblance of a basin with a water jet [was] formed in the center of this garden by an enormous tank twelve feet in diameter and three feet deep, and into which the water was brought by means of lead pipe. All these works cost the Emperor a lot of money, but they contributed to prolong his sad existence by diverting him, for a few moments, from his painful situation.

Naturally, work of such magnitude carried out wholeheartedly was not brought down by the sole will of Bonaparte and the joint efforts of his small court. To help the former general, it was necessary to call on cheap but burdensome workers, which was surprisingly in large numbers on Saint Helena. A large Chinese community indeed occupied the island, regularly augmented by new Confucianist colonists who landed in the harbor of Jamestown after having conveniently borrowed the ships of the East India Company from Canton or Shanghai.

In Longwood, as soon as Bonaparte arrives, several Chinese provided discreet and regular help in the smooth running of the house. Their role will be more and more important and without them, the gardens of Napoleon would probably not have emerged so quickly. Not to mention the small Chinese pavilion that was built and installed on the Longwood property!

The understanding between these obstinate workers and the irascible Bonaparte was not always set fair (who has ever been able to claim a good and permanent understanding with the Emperor?) But undoubtedly a mutual respect was established. This Frenchman, unknown to the Chinese of the time, whom they were assured that he had once ruled the world must, in the garden, clash with the idea that nationals of the Middle Kingdom had of an emperor … Napoleon, in a nanking jacket and trousers, wearing a large straw hat, one day aroused an irrepressible laugh among the workers, so much so that Bonaparte, understanding that they were laughing at his clothes, did not take offense, on the contrary . Speaking to his doctor François Antommarchi (1780 – 1838):

This is my costume! It is indeed quite pleasant. But they must not be burnt by the heat while laughing; I want each of them to also have their little straw hat, it’s a little gift that I give them.

The image that Napoleon Bonaparte awakened in the garden was not only astonishing to Eastern eyes. It joined the intellectual and philosophical sphere in European political discussions. Was it all that he had to exile at the ends of the earth, on an inhospitable island, so that this general, elevated to the rank of emperor, was no longer a threat to the European powers? Now that he was watched night and day, that ships permanently guarded Saint Helena in fear of a flight as sudden as dazzling, now Napoleon Bonaparte became a gardener!

Avid reader of Rousseau in his youth, Bonaparte gave his contemporaries the image of a happy and peaceful reconciliation with ideal nature. This general whom his enemies claimed to be bloodthirsty, could be seen immortalized leaning on a spade, wearing a humble straw hat instead of his legendary cocked hat. The Emperor’s aura was further enriched by it. To the image of a martyr was added that of a great man who, withdrawn from the highest positions of power, easily found the simplicity of “growing his garden”. The effect was striking in Europe, although the reality off Africa was quite different…

This retreat from the world, in a garden – which we then imagined to be almost original – dug a deep ditch with that which had lastingly marked the spirits of the Empire, the garden of Joséphine at Malmaison. Because if the latter was intended as the reconstitution of a luxuriant and exotic nature, it was also an emblem of the rarity and the luxury which opposed it in every way to that of Napoleon on Saint Helena.

Joséphine and the gardens of Malmaison

Probably the nostalgic memories of her Creole childhood led Josephine to develop a sincere interest in botany. His passion for flowers and plants gradually transformed the Malmaison garden into a garden as ideal as it was experimental, a unique and spectacular experience which allowed more than 200 plants to flower for the first time in France. These varieties, true rarities delicately scented and colored, were at the time an ephemeral luxury requiring a care as meticulous as expensive.

Joséphine’s passion for roses is undoubtedly the best known since the Empress achieved the feat of bringing together between 500 and 600 species, both varieties cultivated in beds and other horticultural, distant and fragile, from central Asia, Europe or America and kept in a heated greenhouse.

This immense greenhouse, destroyed in 1827, was the largest of its time. 50 meters long, it was heated by charcoal stoves and could shelter shrubs 5 meters high. Inside, André Thouin (1747 – 1824), then principal gardener of the National Museum of Natural History, was in charge of the species brought back by botanical explorers, themselves sponsored by Joséphine. The collection was incomparable: dahlia, tree peony, hibiscus and camellia flourished for the first time in France among hundreds of other exotic species.