In Saint Helena, Napoleon Bonaparte led a new campaign less military and more about gardening. In 1819, the surroundings of the house of Longwood were enriched with gardens designed and implemented by the Emperor himself. Did the memories of Joséphine's horticultural talents help the Corsican general to win this battle? No doubt, but with less grace than the famous French elegant...

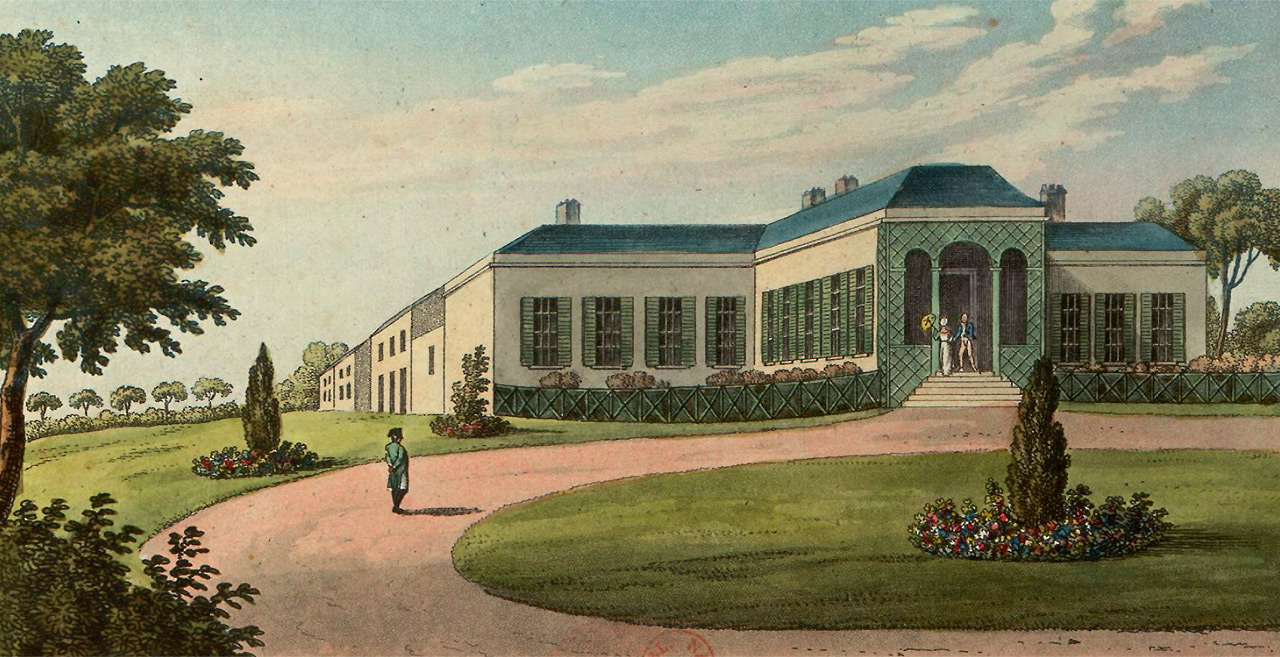

Longwood Gardens in Saint Helena

After five years of exile, the daily rhythm of Napoleon Bonaparte and his little court has slowed down and no longer has the imperial rigor of its beginnings. However…

We are at work from 5 am, and you would laugh heartily to see the Emperor spade in hand.

wrote Count Charles-Tristan de Montholon (1783 – 1853) in 1819.

Because at the beginning of the year, Napoleon resolved to follow (for once) a prescription from his doctors who recommended that he exercise. He could have been content with a daily walk but this kind of activity certainly lacks ambition. Redesign the gardens of his Longwood home, that has more scope! Never in doing things by half, the Corsican therefore undertakes a new gardening career. Two French gardens had already been designed when he arrived in 1815. But in 1819, Napoleon directed himself and with a rod of iron important works of which he drew the plans. And as in the past in the campaigns, he shared the daily life of his soldiers, he was the first to seize a spade or a rake, giving his companions in exile the example of work.

First of all, the new arrangements are intended to provide some shade in the gardens where Napoleon likes to lunch and entertain. A little shade and some plant ramparts against the trade winds soon enabled him to enjoy the outdoors more and to soften his exile. The Count de Montholon, again, testifies in February 1819:

In a few days, he thus succeeded in making us erect, in tufts of bad grass, two circular walls, eleven to twelve feet in height and a diameter of ten toises, as an extension of his bedroom and the library. Sir Hudson Lowe saw there at first only shelter from the wind, and did not object. […] This work done, the Emperor bought twenty-four large trees. He had them dug up with a clod of earth of a cubic height. The artillery agreed to have them transported to Longwood with the help of several hundred Chinese. The Emperor himself directed their plantation in the aisle after the library. […] The garden of the library was enclosed at the height of the steps of the topographical cabinet, or billiard table, as one will call it, by a semi-circular construction in tuff of grass and with steps; each row of steps was planted with rosebushes. […] A semblance of a basin with a water jet [was] formed in the center of this garden by an enormous tank twelve feet in diameter and three feet deep, and into which the water was brought by means of lead pipe. All these works cost the Emperor a lot of money, but they contributed to prolong his sad existence by diverting him, for a few moments, from his painful situation.

Naturally, work of such magnitude carried out wholeheartedly was not brought down by the sole will of Bonaparte and the joint efforts of his small court. To help the former general, it was necessary to call on cheap but burdensome workers, which was surprisingly in large numbers on Saint Helena. A large Chinese community indeed occupied the island, regularly augmented by new Confucianist colonists who landed in the harbor of Jamestown after having conveniently borrowed the ships of the East India Company from Canton or Shanghai.

In Longwood, as soon as Bonaparte arrives, several Chinese provided discreet and regular help in the smooth running of the house. Their role will be more and more important and without them, the gardens of Napoleon would probably not have emerged so quickly. Not to mention the small Chinese pavilion that was built and installed on the Longwood property!

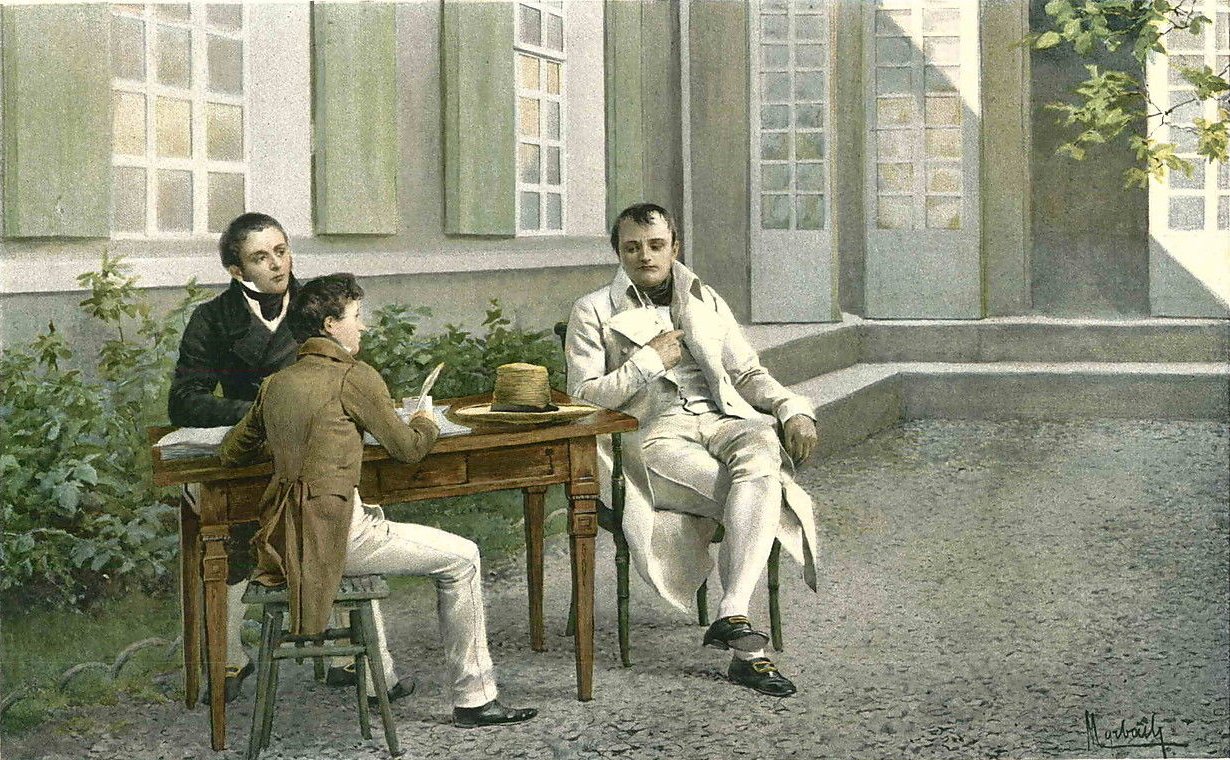

The understanding between these obstinate workers and the irascible Bonaparte was not always set fair (who has ever been able to claim a good and permanent understanding with the Emperor?) But undoubtedly a mutual respect was established. This Frenchman, unknown to the Chinese of the time, whom they were assured that he had once ruled the world must, in the garden, clash with the idea that nationals of the Middle Kingdom had of an emperor … Napoleon, in a nanking jacket and trousers, wearing a large straw hat, one day aroused an irrepressible laugh among the workers, so much so that Bonaparte, understanding that they were laughing at his clothes, did not take offense, on the contrary . Speaking to his doctor François Antommarchi (1780 – 1838):

This is my costume! It is indeed quite pleasant. But they must not be burnt by the heat while laughing; I want each of them to also have their little straw hat, it’s a little gift that I give them.

The image that Napoleon Bonaparte awakened in the garden was not only astonishing to Eastern eyes. It joined the intellectual and philosophical sphere in European political discussions. Was it all that he had to exile at the ends of the earth, on an inhospitable island, so that this general, elevated to the rank of emperor, was no longer a threat to the European powers? Now that he was watched night and day, that ships permanently guarded Saint Helena in fear of a flight as sudden as dazzling, now Napoleon Bonaparte became a gardener!

Avid reader of Rousseau in his youth, Bonaparte gave his contemporaries the image of a happy and peaceful reconciliation with ideal nature. This general whom his enemies claimed to be bloodthirsty, could be seen immortalized leaning on a spade, wearing a humble straw hat instead of his legendary cocked hat. The Emperor’s aura was further enriched by it. To the image of a martyr was added that of a great man who, withdrawn from the highest positions of power, easily found the simplicity of “growing his garden”. The effect was striking in Europe, although the reality off Africa was quite different…

This retreat from the world, in a garden – which we then imagined to be almost original – dug a deep ditch with that which had lastingly marked the spirits of the Empire, the garden of Joséphine at Malmaison. Because if the latter was intended as the reconstitution of a luxuriant and exotic nature, it was also an emblem of the rarity and the luxury which opposed it in every way to that of Napoleon on Saint Helena.

Joséphine and the gardens of Malmaison

Probably the nostalgic memories of her Creole childhood led Josephine to develop a sincere interest in botany. His passion for flowers and plants gradually transformed the Malmaison garden into a garden as ideal as it was experimental, a unique and spectacular experience which allowed more than 200 plants to flower for the first time in France. These varieties, true rarities delicately scented and colored, were at the time an ephemeral luxury requiring a care as meticulous as expensive.

Joséphine’s passion for roses is undoubtedly the best known since the Empress achieved the feat of bringing together between 500 and 600 species, both varieties cultivated in beds and other horticultural, distant and fragile, from central Asia, Europe or America and kept in a heated greenhouse.

This immense greenhouse, destroyed in 1827, was the largest of its time. 50 meters long, it was heated by charcoal stoves and could shelter shrubs 5 meters high. Inside, André Thouin (1747 – 1824), then principal gardener of the National Museum of Natural History, was in charge of the species brought back by botanical explorers, themselves sponsored by Joséphine. The collection was incomparable: dahlia, tree peony, hibiscus and camellia flourished for the first time in France among hundreds of other exotic species.

In a letter addressed to Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau (1765 – 1854) in thanks for a “magnificent collection” of seeds that he had sent her, Joséphine de Beauharnais confided to the prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône:

It is an inexpressible joy for me to see the proliferation of foreign plants in my gardens. I want Malmaison to soon offer a model of good culture and to become a source of wealth for the departments. It is in this view that I have raised there an innumerable quantity of trees and shrubs of the southern lands and of North America. I want each department ten years from now to have a collection of valuable plants from my nurseries.

The gardens of Malmaison were for Joséphine an immense pride and, as noted by Madame de Chastenay (1771 – 1855), “botany owes her in part the extension which she acquired around this time in France. Josephine, who was perfectly aware of it, never failed to remind Tout-Paris. Evidenced by this luxurious herbarium composed of superb watercolors by the painter Pierre-Joseph Redouté and descriptions by the botanist Étienne-Pierre Ventenat. Entitled Malmaison Garden, it is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful flower books ever produced, only 200 copies printed and only offered to Joséphine’s prestigious visitors.

In the foreword Ventenat, addressing the Empress directly, stressed that she had realized “the sweetest memory of the conquests of[son] illustrious husband ”.

In fifteen years, the gardens of Malmaison were not enriched by only hundreds of plant species but also gained in space until reaching an area of 726 hectares. In addition to the greenhouse, an orangery designed by architects Percier and Fontaine in 1800 housed the orange trees in winter that made up the two rows bordering the main avenue of the castle.

Modeling the gardens and its arrangements according to her tastes and desires, Joséphine finally gave way to the vogue for the English garden, the composition of which she entrusted to Louis-Martin Berthault (1770 – 1823), a landscape architect. He designed a park that he punctuated with factories, of which a Temple of Love and a basin surmounted by a statue of Neptune are among the most beautiful. He cleared a bed to install a winding river and a small navigable lake.

The whole reached heights of beauty and elegance in which one detects, as inside the Malmaison, the imperious need of the hostess to accumulate beautiful things.

In 1819, almost five years had passed since Josephine’s death. In Saint Helena, the gardens that Napoleon undertook are surely imbued with the memory of those of Malmaison. But when one was ruled by botany and rarities, the other seemed only to work at recapturing the peaceful memory of a distant stillness. His companions at the time affirm it, Bonaparte spent in his gardens of Saint Helena some of the most pleasant moments of his exile.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».