A recognizable figure among a thousand, Bonaparte is one of the few people who can be identified by the mere shadow of his hat. Napoleon's cocked hat was the signature of his legend.

The Hat That Made the Legend

As far as the portraits of Napoleon go back, only the imperial crown has supplanted the famous cocked hat. An exception of prestige which, however, only manages to equal in our imagination what this forehead wore the most and the best, this simple and black hat, without braid or embellishment. With Bonaparte, and this is a rare thing in history, the title never surpasses the myth. It was his character that made legend. A strategist gifted both in the military and in propaganda, Napoleon had a character that easily accommodated himself to precisely what set him apart from the crowd. For him, creating and maintaining this image should therefore only be a habit that is as daily as it is natural, a habit carried by a recurring outfit that regularly spares him the convolutions that so often come with the visits of wardrobes. This is evidenced by the number of bicornes he used throughout his life: from 1800 to 1812, he had between 120 and 160 delivered, which, at most, makes a dozen per year. Let us count those he lost on the battlefield and this consumption appears to be quite reasonable, almost thrifty if we compare it to the expenditure of the monarchs before him for their toilets. The stingy Letizia (1750 – 1836) must have had genes as determined as her son.

Tirelessly dressed in his gray frock coat – our man had few of them and the last was mended relentlessly even in Saint Helena – Napoleon’s black hats were more inclined to adapt, very lightly, to fashions. To such an extent that the painter Charles de Steuben (1788 – 1856) painted around 1826 a “Life of Bonaparte” through his cocked hat!

The first two are in Paris, we can see the towers of Notre-Dame in the background, then here are ancient columns: Italy and Egypt. The fourth cocked hat rests on olive branches, a symbol of peace, perhaps the Consulate, Austerlitz or Tilsit then an eagle rises towards the fifth central hat, with the profile of a crown, before the last three bicorne hat waver. The sixth, on the ground, faces the glowing sky of the flames ravaging Moscow. Then it’s a raised hat that leaves behind the snow of the terrible retreat from Russia: the flight of the Eagle and the Hundred Days precede a last cocked hat which has tipped, face down with the spur of Saint Helena at the back. A life summed up in cocked hats, a few years after Bonaparte’s death. All different bicorne who nevertheless embody the same person. Historical construction do you think? Lyricism of the legend you say?

This is to ignore the talent of communicator of Napoleon who, soon after his victories in Italy, put nothing in the hands of fate and everything in those of Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825). The artist painted his Bonaparte crossing the Great Saint-Bernard with as a model the outfit and the cocked hat that the general wore to Marengo and that he lent him especially (a loan and not a gift, undoubtedly the genes of the Corsican mother are tough). And what do we see in this work? A general “calm on a fiery horse” in the words attributed to Napoleon. But above all, a man wearing a hat whose embroidered border already shines like a crown. The painting’s vigorous guidelines are stabilized by the almost straight line of the cocked hat’s edge, the same as that of the general’s gaze. To follow the general, one must certainly follow his hat.

This cocked hat, which varied in shape from the Italian countryside to Saint Helena, always measured between 44 and 47 cm in length and 24 to 26 cm in height. Those of Napoleon have the particularity of not being provided with the sweat band that the Corsican could not bear and that he systematically removed. Of the four taken with him to Saint Helena, one was placed in his coffin, which is to say the importance Bonaparte attached to his bicorne and the symbol they represented in the eyes of his intimates.

Today between 20 and 30 bicornes are authenticated, many are kept in museums, some in private hands. In April 1969, the famous champagne house Moët & Chandon acquired a cocked hat for the sum of 140,000 francs. In 2014, a Korean businessman bought himself one of Napoleon’s hats for 1.8 million euros. The following year, the bicorn hat worn in 1807 during the Battles of Eylau and Friedland, as well as in the Treaty of Tilsit was sold by auction house Christie’s London for £ 386,000. Proof, if necessary, that the bicorne could become a natural metonymy of Napoleon. The only silhouette of the Courvoisier cognac house could finally convince us.

The Napoleonic Cocked Hat

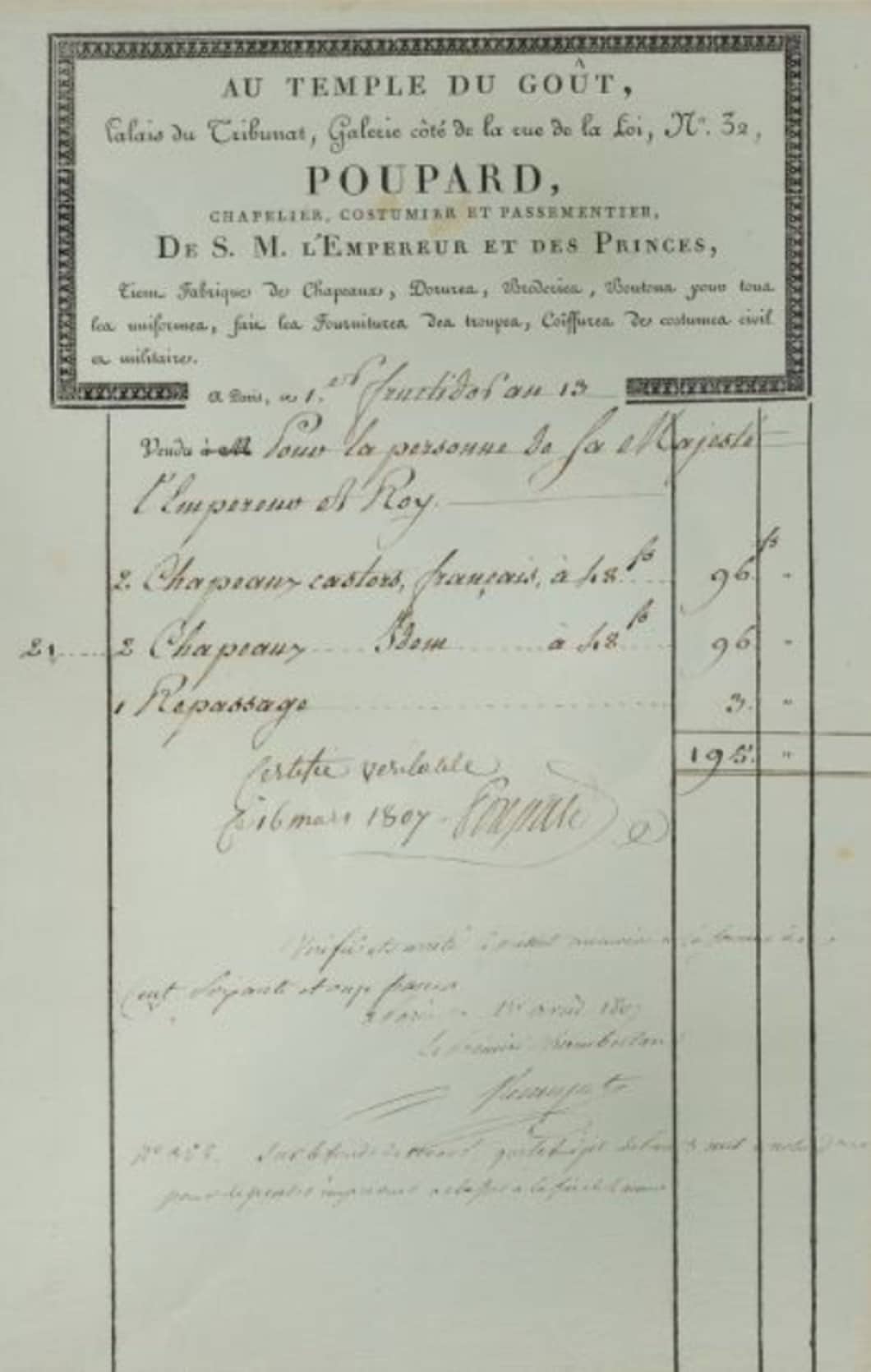

Because all his life, he was not only faithful to this style of hat but he was also to his hatter! The said Poupard soon took the distinction of “Hatter, costume designer and trimmer of the Emperor and the princes”, in the event that his sign subtitled “Le Temple du Goût” was not enough to let know everyone that no other craftsman was more qualified than him to cover the head with the most beautiful headdresses. The era was not afraid of superlatives, and Poupard had every reason in the world to boast. Because it was he who, from his Parisian boutique at the Palais – Royal, delivered the famous “French hat” to the General, First Consul and then Emperor. Initially sold for 48 francs, the bicorne price suddenly rose to 60 francs from 1806. For the same price, the common person could buy a thousand eggs or even a small fifty cheeses, two of the main popular foods at that time.

If the price of these bicornes was so high for ordinary people, it was because Bonaparte’s choice always turned to those made from beaver skin. This excellent quality material, sought after for its resistance and fashionable since the 16th century, undermined the population of these peaceful animals, a few colonies of which lived in France and more numerous in northern Europe. In the 17th century, the European beaver had almost disappeared and we therefore set out to eradicate its American cousin in an approach far removed from our contemporary concerns.

Curious peculiarity: the Europeans bought from the North American natives only used beaver pelts! It was indeed more interesting in terms of work to provide themselves with beaver pelts already softened by the hunters who wore them as a cloak for several months, so that the pelts reached the hatters shops ready for use. There were two qualities of beaver hat: the half beaver (demi castor) and the beaver (castor). The nuance in this case was not due to the entire animal but to the use that was made of its skin and hair.

The half beaver was a classic wool felt with beaver hair glued onto it, while the beaver hat was made entirely from animal skin. The first was obviously more affordable than the second which, due to its rarity since the 17th century, had become a luxury item.

No need to look for beaver hair on these historic bicornes, the softer and old leather no longer wears one. Nevertheless, these so-called “black beaver” or “fur felt” hats were of the best quality, resistant to bad weather as well as to the dictatorship of taste (and in this area, our Poupard knew something about it, he who led the Temple). These resistant and sober, soft, brilliant and elegant headdresses suited, one understands, the character of Bonaparte. With no other ornament than a tricolor cockade slipped into a black silk braid closed with a button, the Napoleonic cocked hat was practical, solid and elegant. An unbeatable quality / price ratio which soon won over our Bonaparte who, like a good soldier – and son of Letizia – sought above all efficiency and fair expenditure.

The first bill has not yet suffered the inflation of 1806 and the price of the “French hat” in beaver remains at 48 francs. The invoice is approved and signed by the Comte de Rémusat (1762 – 1823), the Emperor’s first chamberlain. The second bill is interesting by comparison. The first item invoiced to Napoleon I, namely “a full-size embroidered hat”, is sold for 660 francs, a fortune compared to the simple black beaver hat! The bills from Poupard to Bonaparte testify both to the latter’s simplicity in fashion, since he always preferred simple beaver hats to complicated headgear, as well as to his perfect awareness of assets of clothing for its communication and personal propaganda. If the bicorne comes back precisely as a signature, both in Poupard’s invoices and in the painted and written portraits we have of Bonaparte, it is because they are part of the legendary silhouette modeled by Napoleon. A silhouette all created by oppositions.

A French history of the bicorne

The bicorne inherited several modifications from a large military headgear from the beginning of the 17th century. To give birth to the famous French hat, it must indeed go through the no less famous hat of the musketeers. This large hat, regularly decorated with a feather or a ribbon, was formed from a large circle of felt; The effect was both spectacular and very elegant. But, it must be admitted, impractical. At a time when fighting was exclusively in contact with the adversary, swift and broad gestures at best disheveled and, at worst, hampered the fighter’s movement. The ridiculous, which we already knew in the 17th century, does not kill people, but defeats could not be excused by the whims of fashion. So it was decided to roll up the edges of the felt hat and steam harden the whole thing; thus the superb tricorn was obtained. The appearance was safe and the fighter at ease, the future of the tricorn hat looked bright for most of the 18th century. As much as in the 18th century, aristocrats wore it more on the arms than on the head to avoid dropping the powder from the wigs. In 1726, the Mercure de France ironically noted:

The hats are a reasonable size, they are worn under the arm and almost never over the head.

We therefore came to manufacture almost flat hats intended more for the arm than the head, hence their name of chapeau-bras, and among them the tricorn was a great success and establishing its noble label, which the Revolution will remember.

However, a horn still hindered those who wielded the rifle. Either, the tricorn was therefore sometimes amputated of a horn but coexisted with a bicorne worn “in battle” (each horn parallel to the shoulders), so as not to obstruct the view, a manner which finally became widespread in several regiments, between 1786 and 1791.

During and after the Revolution, the tricorn too associated with the Ancien Régime disappeared from the hatters’ shops. On the other hand, the military and bourgeois bicorne enters a prosperous period. The Republic quickly adopted it for its generals and representatives of the legislative and administrative power. The fashion is then to wear it “in column”, the horns perpendicular to the shoulders. Bonaparte, like all Republican soldiers, wears this headdress that we imagine then in half-beaver or wool felt because the young man was not rolling in it.

But by the end of the 1790s, the Italian campaign gave the young general the opportunity to seal the first stone of his legend in the making. During battles, Napoleon did not wear his cocked hat “in column” or “à la Frédéric II” (sideways, as the Prussian did) but “in battle”. From then on, it is easy to recognize the general in the chaos of the fighting. Quickly identifiable thanks to his hat, Napoleon Bonaparte already sits part of his mythical silhouette. The appearance will stand out even more when he adopts his famous gray frock coat. This outfit to which he remained faithful all his life suggests, beyond his taste for military simplicity which brought him closer to his soldiers, a perfect awareness of the potential of clothing as a political tool. For if all of Europe wore the bicorne at the turn of the 19th century, from Frederick II of Prussia (1712 – 1786) to Nicholas I (1796 – 1855), it seems nevertheless that it was created only for one man. A historical unicum skilfully mocked by the Jean Rostand character of Count Metternich (1773 – 1859) :

Because it is from a hatter that the legend leaves,

The real Napoleon, in short … is Poupard!

Edmond Rostand, L’Aiglon, 1900

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Congratulations!

You are now registered to our Newsletter.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie de Lagerac est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et l'auteure du blog « L'Art de l'Objet ».