The cliché is worn out. However, and as often, the stereotype settles on fertile and well-documented soil. Did the madmen taking themselves for Napoleon I really populate the insane asylums? Were they all mad or did they take advantage of a historic moment of confusion following Bonaparte's exile?

From the Revolution to the end of the Empire, in the throes of instability and violence

The adoption of the guillotine, recommended by Mr. Guillotin to establish equality between citizens even in the execution of the capital punishment, had consequences as incisive in the flesh as in the minds. So when on January 21st, 1793, Louis XVI was beheaded under the heartbroken eyes of Philippe Pinel (1745 – 1826), precursor of psychiatry in France, the doctor denied being a royalist but felt that if this troubled period literally caused the loss of their head for many citizens, others also lose it in a much more insidious way.

Terror not only threatens bodies, it also threatens minds. Because the daily lists of the condemned maintain, during weeks sometimes, a fear leaving no rest to the citizens likely to be led to the scaffold. Some minds do not resist such torture and sink into madness: “delirium, the subject’s bulwark against its own collapse has a lot to tell us about political violence” underlines Laure Murat, historian and author of The man who thought he was Napoleon.

The Empire does not put an end to the violence and uncertainty that are the daily life on the eve of the 19th century. The parenthesis is far from enchanted and it is almost a whole century which bears the stigmata of the Revolution. From 1789 to 1871, political regimes followed one after the other, without sustainability but always accompanied by political and social violence. The disturbances not only agitate the upper echelons, they are also expressed in the streets. How to endure such instability on a daily basis? The contemporaries of the time know too well that a political opinion for a time unanimous – and sometimes even rewarded – can turn just as quickly into condemnation at best social, at worst, to death. There is enough to lose your head there without having recourse to the terrifying “Louisette”, affectionate nickname of the guillotine in homage to one of its designers, the doctor Antoine Louis (1723 – 1792). Nevertheless, shady perspectives are opening up to the most solid … and the most disturbed minds?

Identity Theft: the Fake Napoleon I

The Restoration of 1815 is accompanied by an epidermal reaction of Louis XVIII confronted with the memories of the Empire. It is essential for the royalists to overwhelm the Napoleonic legend with all evils because the suppression of all its memories will not be enough to silence the Bonapartists. Everywhere in France, the portraits of Napoleon I, of the imperial family, the emblems and all the representations directly or indirectly touching Bonaparte are systematically destroyed, erased, scratched. The royalists’ solution is ultimately worse than the evil they are striving to boast about. Not only a trade in commemorative objects is set up (the tastiest of which is undoubtedly that of the waffle molds decorated with the imperial profile) but especially since the booksellers and hawkers are no longer authorized to disseminate the image of the general Corsican, impostors will have full latitude to play on the memory of a vague resemblance between their physiognomy and that of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Thus begins the short adventure of Jean Charnay, a former soldier in his thirties converted into a very curious activity of “teacher and peddler” that a woman recognizes in June 1817 as the fallen emperor. Poor and hungry, he does not particularly want to contradict this woman who does not budge: his face is identical to the profile of the old coins bearing the effigy of Napoleon I! It is well worth a good meal, the usurper does not deny… Charnay takes to the game of confabulation and seems convincing enough to get free food; he sometimes even obtains up to the totality of the savings of a few subjugated inhabitants. However, he does not keep everything to himself, the man is intelligent. He is keen to keep his rank because this is also the usurpation that fills his stomach daily. So here he is distributing money to the poor, a perfect disguise for the one who was still a destitute just a few weeks before. Because the masquerade lasts two months and takes the paths of Ain and Saône-et-Loire until Charnay-Napoléon was arrested on August 4 of the same summer 1817 and then imprisoned.

A previous usurper had been less successful in 1815, still in Ain, he only held out for two days. Jean-Baptiste Ravier, a former sergeant-major of the Grande Armée, also in his thirties, did not take much advantage of his imperial status before being imprisoned. We will not fail to raise the common point which unites these two characters as well in their misfortune as in the means which they employed to remedy it. Both were elders of the Grand Army. However, we know the unfortunate fate of many Grognards after the fall of the Empire. It was necessary to eat well and the confusion following the surrender of Napoleon Bonaparte was conducive to plant seed of doubt in people’s minds.

All the more so as Napoleon was not at his first coup and mastered like no one else the art of returns as dazzling as they were unexpected. The population was therefore legitimately entitled to doubt the emperor’s defeat and his exile when these characters appeared, claiming to be Napoleon I. Very clever the one who could accuse the credulity of the inhabitants of the provinces in such troubled times. On the other hand, these funny anecdotes are revealing of the powerful memory which Bonaparte left in the spirits, everywhere on the territory: no need for a perfect resemblance nor even to be of the same age as the Corsican; the evocation, the talent of orator and the bearing are often enough.

The memory of the great man is not always suggested by the impostor and recognized by the admirer. Sometimes a grain of madness comes to stop the machine and the false Napoleon is not only motivated by poverty. The example of Brother Hilarion – whose real name is Joseph-Xavier Tissot (1780-1864) – is edifying.

We are in 1823 and Napoleon Bonaparte died in Saint Helena for two years already. In 1822, Brother Hilarion, an unknown – for the moment relatively discreet – acquired a small castle in Lozère which he intended to welcome the needy and the weak of mind. No fees are charged for these patients or their families. Brother Hilarion and the few religious who accompany him take care of them and, unlike the unhealthy asylums which are the ordinary of unhappy disturbed patients, the Lozère establishment is a remarkable example of care and good treatment.

Now, Brother Hilarion is not just a Good Samaritan. His disturbing resemblance to the emperor, his charisma and his ease as a speaker disturb many inhabitants of the region who report to anyone who wants to hear them that Bonaparte is well and truly alive! He is only concealed under the monastic costume, undoubtedly to recover a peaceful life far from the risks of politics. The information is so convincing that it ends up arousing the interest of the sub-prefect Armand Marquiset. If Napoleon is back despite his announced death, Marquiset should be sure of it; this man would be quite capable of coming back from the dead!

Marquiset is quickly reassured. While he recognizes that Brother Hilarion expresses admirably and possesses the regular features reminiscent of those of Bonaparte, the sub-prefect also notes that the resurrected Napoleon sometimes seems “more disturbed than his patients”. Brother Hilarion will open several hospices and will strive to protect the weak of spirits or the insane. Despite a notoriety that will extend to several neighboring regions, Joseph-Xavier Tissot will have to give up his hospices for lack of means. Today, he is considered by some to be the forerunner of alienists, or at least an advocate of worthy psychiatric care, at a time when the idea was only just beginning to be heard.

The madmen who thought they were Napoleon: an evil that does not spare celebrities

The exile of Napoleon Bonaparte only reinforces the fascination for this character to whom nothing and no one could resist. Subjecting a large part of the European sovereigns only to his strength of character, his intelligence and his military and strategic genius above all, Bonaparte knew how to emancipate himself from the need for an aristocratic and historical ancestry to rise from a poor island nobility to the rank of emperor reigning over territories beyond the natural borders of France. Fallen for the first time, returned in a masterful tour de force and without any recourse to violence, Bonaparte is the perfect embodiment of Nietzsche’s Übermensch: freed from dynastic legitimacy, from the moral common to men and from social control. Napoleon Bonaparte is a self-made man , a charismatic and fascinating personality who inaugurates a new era where individualism is increasingly valued and encouraged.

In the troubled context of the 19th century, extraordinary historical figures are a solid anchor for those who lose their minds. Bonaparte, invulnerable and pugnacious, thus becomes a personality easily endorsed by the insane. Especially since the costume requires little investment: a frock coat, a bicorn hat and voila!

Thus, after the return of the ashes of Napoleon I in December 1840, Doctor Auguste Voisin saw about fifteen emperors enter the asylum of Bicêtre. And that does not go easy! Because like their model, each emperor is angry, capricious and authoritarian. Not supporting the contradiction, the meetings between two imperial personalities lead to inevitable fights where each one claims his legitimacy to the throne and accuses the rival of shameless imposture …

These madmen, convinced of being Napoleon I, are the occasion for Étienne Esquirol (1772 – 1840), a pupil of Voisin, to study and describe in detail this newly appeared disorder and baptized proud (or ambitious) monomania, of which the main characteristic lies in the astonishing consistency of the patients. The latter in fact retain all their intellectual capacities and their common sense, except of course their delirium of identity.

Yet it would be wrong to believe that Napoleon has a monopoly on monomaniac delirium. Although he wins with flying colours, he is battling it out with other prestigious competitors. Laure Murat thus identifies several notable personalities pleasing delusional patients: Louis XVI, Jesus or Mahomet are the most common. What do they have in common? They are out of the ordinary. Living a unique, extraordinary destiny, they extricate themselves from reality. Moreover, the insane are less raving about the person incarnate than about his title or the idea that one has of this person. Rather than embodying Napoleon Bonaparte, the madman embraces the personality of an emperor of unsuspected power.

Should we be surprised that Nietzsche (1844 – 1900), at the dawn of the delirium which will lose him in 1900, took a brief moment himself for Napoleon? In the same vein, the philosopher Auguste Comte (1798 – 1857) had already shown several signs of madness, as when leaving asylum, he signed the name of “Brutus Bonaparte Comte” in the register. Bad times for philosophers!

More recently, legend has it that the actor Albert Dieudonné (1889 – 1976), who played Napoleon for the eponymous film by Abel Gance (1889 – 1981) in 1927, was buried in the Bonaparte costume he wore on the filming. Whatever the reality, many of his colleagues at the time conceded that the actor narrowly escaped madness. Better! The director himself devoured by the personality of the emperor found himself psychic correspondences with the deceased emperor …

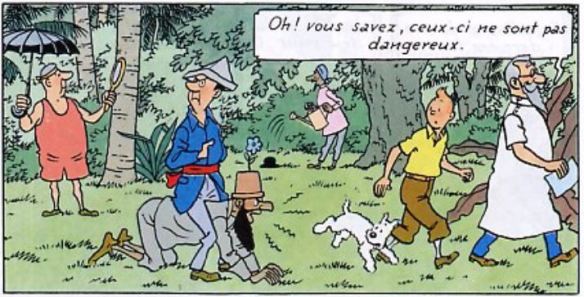

Even today, the stereotypical image of the madman invariably represents a man hand in the jacket, head held high and looking intractable. Napoleon Bonaparte, an icon as popular as his insane ersatz, never ceases to inspire… even the boards imagined by Hergé!

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie de Lagerac est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et l'auteure du blog « L'Art de l'Objet ».