Elaborated from the medieval recipe of a Florentine convent, Cologne is first presented by its creator as a remedy rather than a cosmetic fragrance. A perfectly natural consideration in the 18th and 19th century that echoes in our contemporary use of essential oils.

Cologne: the Panacea of the 19th Century

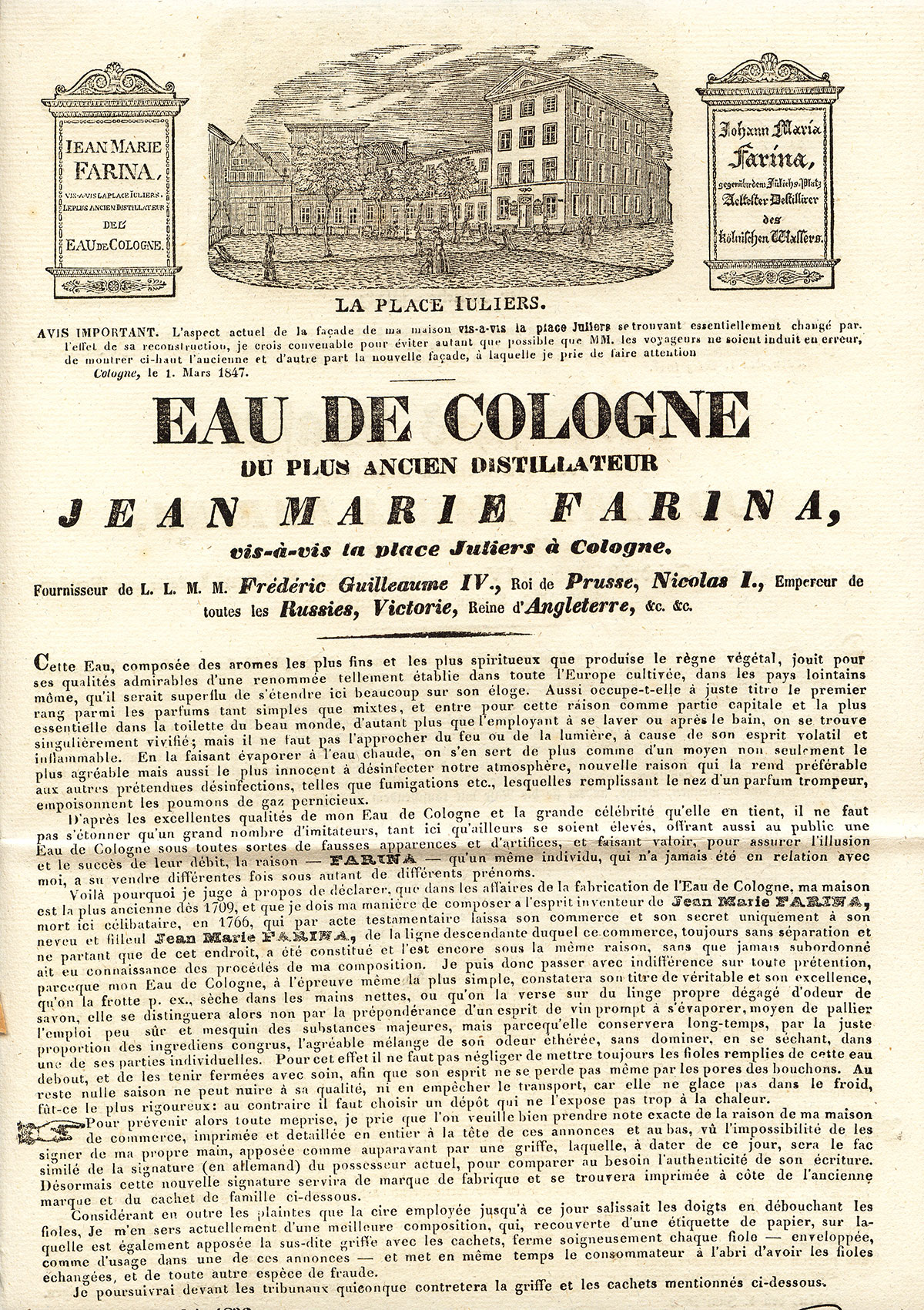

The “Acqua Mirabilis” as it was first named quickly met with success as it was understood that it was aptly named. When it was marketed in France under the term “Eau Admirable” by Jean-Marie Farina (1685 – 1766), the latter was not stingy with details announcing in an 18th century prospectus that “if we wanted to do the detail of all the pains with which this water is suitable for, it should be necessary to do the detail of all the infirmities to which the human body is subject.” This is a postulate that does not lack panache or temerity. And Farina went on to enumerate the various affections with which the Cologne overcome: apoplexy, migraine, eye pain, scurvy, gout, cuts and abrasions, paralysis, and that of man as well as animal! It also teaches the different ways in the 19th century to use this water: ingesting by pouring a few drops in wine or broth, apply it as a compress on damp cotton and especially rubbing the body regularly and especially when leaving the bath “in the time that the pores are open“.

The freshness it provided and the active principles that made it undoubtedly brought immediate relief to anyone who used it, but perhaps Farina was a little too confident in saying that his water, as delicious as it is, overcoming all the sickness. Moreover the Cologne was no longer in the category of drugs since the decree of 18th August 1810, which should not displease the Emperor who, according to Emmanuel de Las Cases (1766 – 1842), “does not believe in medicine or its remedies, of which he made no use […] He defends the thesis that it is better to allow nature to be done instead of encumbering it with remedies “. However, Cologne is the result of a pharmacological and medical reflection.

Do you like this article?

Like Bonaparte, you do not want to be disturbed for no reason. Our newsletter will be discreet, while allowing you to discover stories and anecdotes sometimes little known to the general public.

Congratulations!

You are now registered to our Newsletter.

Eau de Cologne: Medicine Before Cosmetics

In the Middle Ages and until the beginning of modern times, air quality (dry, wet, cold or hot) was considered the sole cause of disease. The scents of spice, herbs and flowers were intended to balance the body: each air quality matched assemblages of scents to prevent disease. Carried in pomander or mixed with vinegar, herbs, spices, barks, and flowers were considered remedies before being considered as cosmetics. The use of Cologne inherits this tradition from the rich therapeutic active principles that compose it. Formulated with natural essential oils, it is not far from our contemporary aromatherapy practices.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et de l’antiquité et auteur du blog « Objets d’Art & d'Histoire ».