The mere mention of his name sends shivers down the spines of Europe's greatest men. So when Napoleon surrendered to his enemies, the Allies wanted only one thing: to get rid of the ogre once and for all.

The beginning of the end: Waterloo

It is said that Napoleon was to remain an islander. Born in Corsica, the emperor was exiled after his first abdication in 1814 to the island of Elba, off the Italian coast. He was almost sent to St. Helena in 1815, as Elba was rightly criticized for its lack of security. Ironically, the British government refused the move, which only delayed the deadline for Napoleon’s last cruise.

Certainly, the island of Elba lacked the height to keep the little corporal from sneaking out. Leaving the tiny kingdom he had been granted after three hundred days, he returned to the mainland and set off for the Flight of the Eagle, initiating the Hundred Days (which counted his time back in power), ousting Louis XVIII before being defeated on June 18, 1815 at Waterloo by the hastily and successfully reformed Allied coalition.

After this crushing defeat, Napoleon managed to leave the battlefield and began his escape. He first headed for Paris, where he hoped to play a political role, but failed. He then took the road to Malmaison, giving Joseph Fouché, then head of the provisional government, enough time to betray him by reporting the deposed Emperor’s plans to the Allies already on his tail. Napoleon’s plans were now known: to reach Rochefort and set sail for America. The British fleet was immediately mobilized to block his escape. In the meantime, Louis XVIII’s policemen set off to catch up with the infernal fugitive.

Napoleon now had two options: to escape by hiding in a fast boat, capable of escaping the English blockade, and placed at his disposal, or “to abandon himself to the generosity of the Regent of Great Britain”.

"Like Themistocles, I have come to sit at the hearth of the British people", Napoleon becomes an Anglophile

The game is afoot, and each protagonist has a card to play. Napoleon doesn’t speak a word of English, he doesn’t understand British culture, but he’s not unaware of Albion’s liberal right of asylum. At the same time, the British claim Napoleon as their deserved trophy. After more than twenty years of fighting him, they asserted their right to make him a prestigious prize of war. The Allies are not opposed to this demand, as long as Great Britain takes responsibility, at its own expense, for the prisoner’s upkeep and close, necessary surveillance. If the victorious coalition at Waterloo had its way, Bonaparte’s fate would have been sealed in a radical and expeditious manner, and at no extra cost.

Meanwhile, Napoleon refused to flee into hiding, like a common fugitive. All the more so as the legislation in force among his English enemies could work in his favor, and give him a chance to live out his days in peace. In any case, that’s what Cambacérès and other eminent jurists were betting on in the wake of the Belgian debacle.

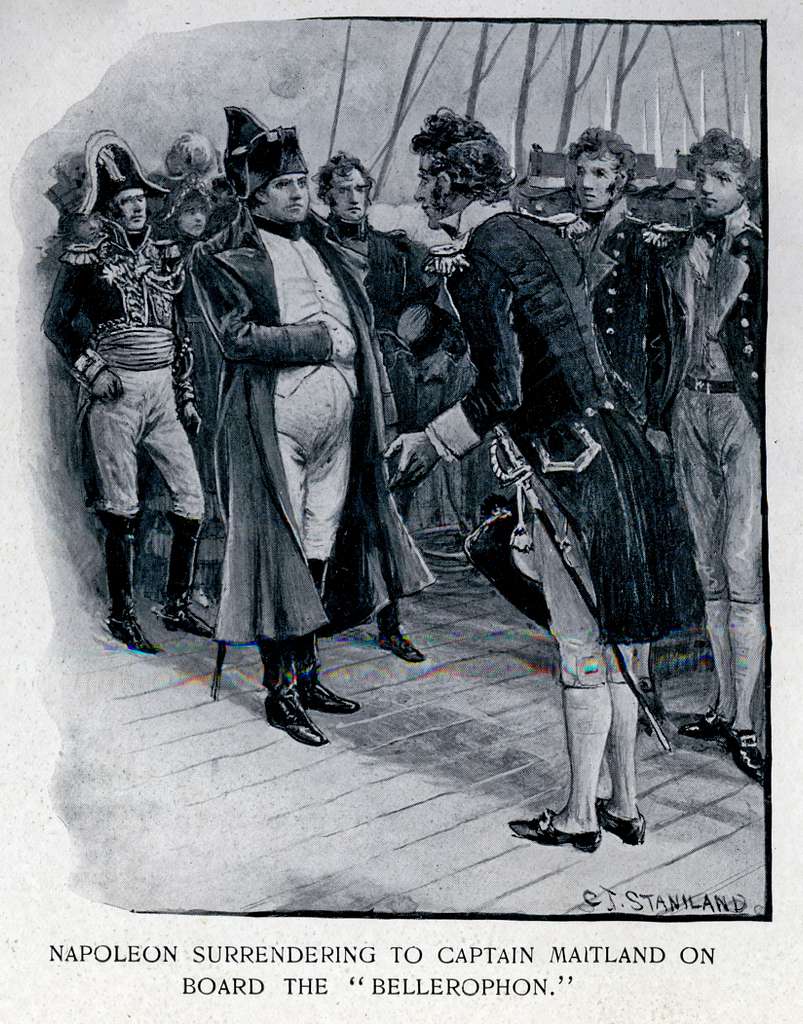

So the Emperor played his last card and, as a show of (false?) good will, surrendered himself to the English forces by joining the Bellerophon, a ship anchored in Rochefort harbor, shortly after 6am on July 15, 1815.

I have come to place myself under the protection of your prince and your laws […] The fate of arms has brought me to my cruelest enemy, but I am counting on his loyalty.

The next day, the ship sails for England. Meanwhile, in London, we still don’t know what to do with this prestigious, but oh so cumbersome prisoner. Send him to prison in England? To Scotland? Suggestions of St. Helena, Malta and Gibraltar were once again on the table. The most important thing, it was thought, was to find the most remote and perfectly secure location. But Bonaparte’s popularity was not to be taken into account.

An unexpected welcome in Torquay harbour

The orders transmitted to the Bellerophon were very clear: Napoleon was not to leave the ship or set foot on British soil, as the law of the land would have to be applied to him. And given the welcome Bonaparte received once the ship reached the Devon coast, these precautions were not too much to ask!

As soon as the Bellerophon docked in Torquay harbor at dawn, news of its famous passenger spread like wildfire. Soon dozens, then hundreds, and by the next day nearly a thousand canoes loaded with curious onlookers were trying to catch a glimpse of the famous emperor. And, against all odds, British phlegm wins out over fear, anger or revenge. Canoeists greet Bonaparte in a friendly manner, women wave their handkerchiefs and others even throw him flowers!

On deck, Napoleon naturally found the welcome charming. Reassured by this joyful arrival, he took up his pen and addressed a letter to the future George IV (1762 – 1830). In this missive, which never reached the Prince Regent, Bonaparte showed his humility, announcing that he wished to “come and sit at the hearth of the British people”. In all simplicity, he asked the future sovereign for a small estate near London, where he and a few of his retinue could quietly end their days. It seems that Napoleon already saw himself as a gentleman farmer, happily observing the course of the world from his luxury cottage!

Having no doubt dreamed of making England part of his empire, it would be amusing if the enemy island were to become his land of asylum. But that doesn’t amuse some members of the British Parliament! If he stays too long in Torquay, this damned Frenchman will end up winning over popular fervor if we’re not careful! All the more so as it only takes one of his two feet treading Devon soil for him to be able to legally lodge a habeas corpus petition, which we fear will be honestly granted.

Habeas corpus and Napoleon's disillusionment

This was the pride and weakness of the English. The Magna Carta, drawn up in June 1215, established the respective rights of the king and the barons, as well as the Church and the towns, in the government of the kingdom. At the beginning of the 19th century, it was still in force (with a few exceptions, especially in Napoleonic times). Article 39 states that “No free man shall be arrested or imprisoned, or dispossessed of his property, or declared an outlaw, or exiled, or executed in any manner whatsoever, and we shall not act against him nor send anyone against him, without a lawful judgment of his peers and in accordance with the law of the land.”

In 1679, this text was supplemented by theHabeas Corpus Act guaranteeing individual liberty, in order to avoid arbitrary detention through judicial justification, by giving the detainee the right to appear immediately. This applied to anyone on British soil. Napoleon and his advisors believed that these laws would provide the deposed emperor with an honorable retirement. But he still had to put his foot down. And everything was done to ensure that never happened.

The island of St. Helena was chosen as Napoleon’s last place of residence. The fact that it was lost in the middle of the Atlantic, between Brazil and Angola, was already an advantage. Unlike Elba, Napoleon would be so far from any continent that to escape would be considered a complete absurdity. Added to this were reports by specially commissioned officers measuring the island’s advantages as a prison. Firstly, its small size meant that it could be defended with very few resources, especially as St. Helena was already bristling with English guns and only accessible via the port of St. James, the rest being steep, immense, sharp cliffs. Few people live here, and any stranger is immediately spotted. And, the icing on the cake, the island doesn’t belong to the British crown, but to the East India Company. The nuance is subtle, but legally precious, as it prevents Napoleon from falling under the authority of Magna Carta and habeas corpus. The terms of the detention were carefully drawn up by both parties, the government and the shipping company, so that the English were solely in charge of Napoleon’s detention. A special commissioner was appointed to represent the Russians, Prussians and Austrians.

Napoleon’s fate was sealed. He may not have set foot in England, but he is about to taste the delights of his empire. He may not have set foot in England, but he’s about to taste the delights of his Empire. Ironically, the English can say the same of his freshly collapsed empire.

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

Félicitations !

Vous êtes désormais inscrit à notre newsletter.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie de Lagerac est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et l'auteure du blog « L'Art de l'Objet ».