18 Brumaire, Year VII: Napoleon Bonaparte orchestrates the slowest coup d'état in French history.

An emperor is neither made alone, nor in a day. His rise to prominence is based on iron will and hard work, luck and the ability to surround oneself with the right people.

Our young Corsican was in his early twenties when the Bastille was taken in July 1789. From that pivotal moment onwards, his career began in earnest. In September 1793, he was appointed captain at the siege of Toulon, and became a general in December. In 1796, he left for the Italian campaign. France was then a Republic, the first in its history. Scandalized by different periods, it opened with the National Convention – infamous for its episode of the Terror – from 1792 to 1795. A new constitution ushered in a new era: the Directoire, from 1795 to 1799. Under this regime, executive power was divided between five directors, heads of government who were regularly replaced, and ministers. Legislative power was entrusted to two assemblies: the Council of Elders – forerunner of the Senate – and the Council of Five Hundred (comparable to our National Assembly). This political system, designed to avoid tyranny, was based at the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris.

It was under the Directoire that Napoleon began his historic rise, taking advantage of the difficult context in which the government was mired. The political instability and violence that accompanied the Revolution went hand in hand with an exhausting battle against European coalitions directed against the French Republic, as well as a fierce struggle, within the country itself, against the Chouans, the royalist insurgents. The already deplorable economic situation did not improve. While the Directoire set about laying the foundations of a solid financial system, cleaning up finances and making direct taxes fairer, indirect taxes multiplied and increased considerably. Public opinion focused on forced requisitions and loans, constant fighting and trial and error. However, the foundations laid by the Directoire would serve the next regime, the Consulate, headed by Napoleon Bonaparte.

The deserter general: Napoleon from Egypt to Paris

It was recriminations against the Directoire and serious military setbacks on the German, Italian and Swiss fronts that created the opportunity Bonaparte was able to seize. Considered the hero of the Italian campaign, the successful general had been in Egypt since May 1798. In July, the Battle of the Pyramids cemented the general’s prestige, while Admiral Nelson sank his dreams of the Orient on August 1 in the bay of Aboukir: the French fleet was wiped out. More victories – and more defeats – lay ahead, until the victorious land battle of Aboukir on July 25, 1799.

At the end of the latter, news of the French political situation reached him, and it was far from cheerful. The Italian conquests he had so lavishly staged in his polished propaganda were lost, and others seemed on the verge of being lost. Well aware that his flattering reputation as a victorious, peacemaking general was still very much alive in France, carefully nurtured by his brother Lucien (deputy to the Conseil des Cinq-Cents), General Bonaparte decided to return to France, without having been ordered to do so. In short, he deserted, a tasteful choice that matched the North African landscape.

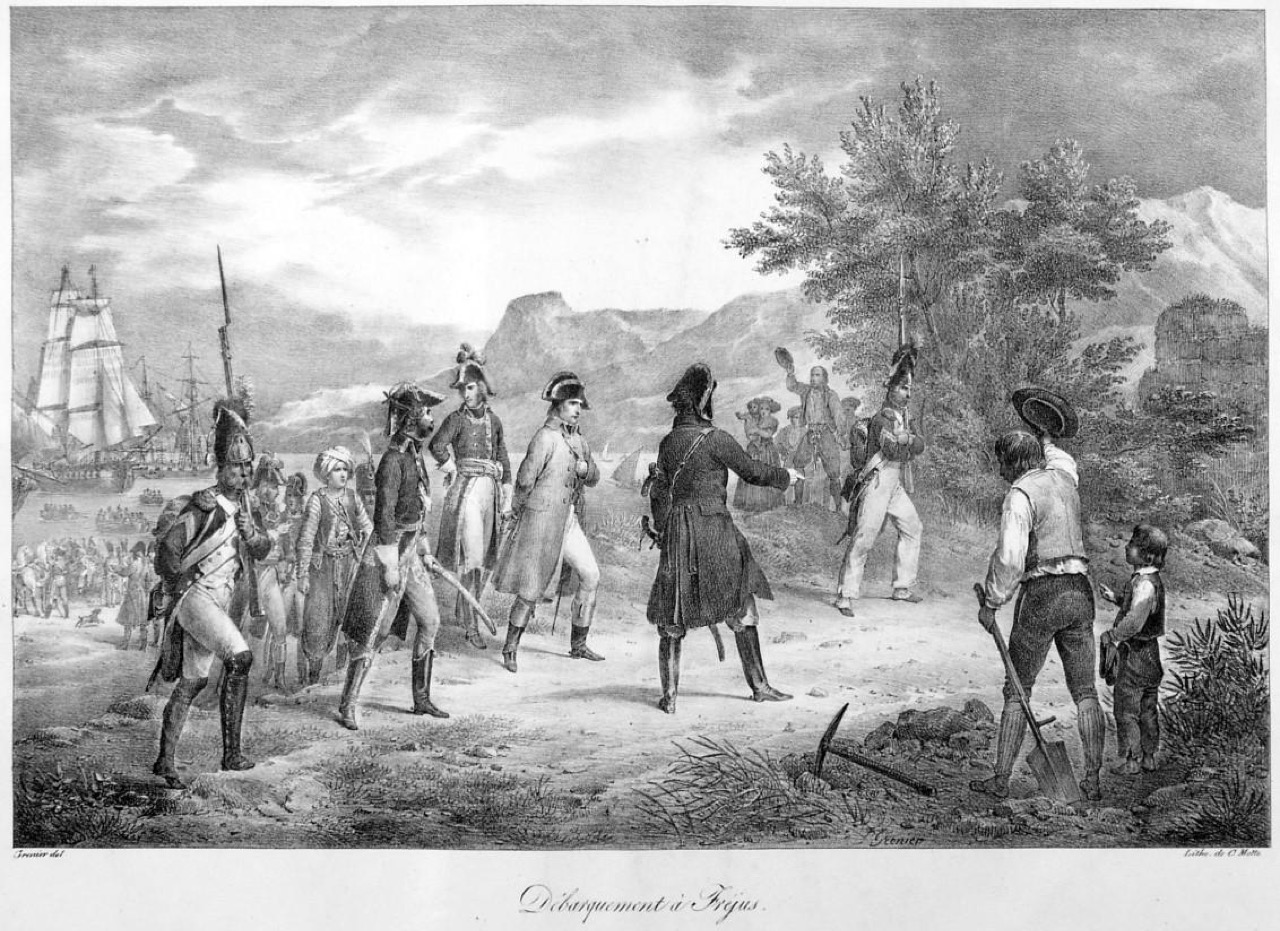

Surrounded by the British, he nevertheless managed to escape to England, taking with him Chief of Staff Louis-Alexandre Berthier, General Joachim Murat, Brigadier General Auguste-Frédéric Viesse de Marmont, Major General Jean Lannes and Battalion Chief and Brigadier Géraud-Christophe-Michel Duroc. Nor did he forget the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet and the great narrator of his adventures, the writer Dominique-Vivant Denon. This fine crew arrived in Fréjus on the evening of October 8, and Bonaparte and Berthier left immediately for Paris.

Triumphant return

In the meantime, the French military situation had recovered, but the Directoire is not in the odor of sanctity, and all that was needed was the surprise arrival of the general to add fuel to the fire. All the way to Paris, the deserter was hailed and welcomed as a savior (not to say a king). While his superiors should, at the very least, have raised their voices, the news of his dazzling victory at Aboukir reached Paris ahead of him and made the headlines. Bonaparte, who had grown impatient during the Mediterranean crossing, worried about arriving too late and missing his chance, could not have entered the capital under better auspices. He now appeared to public opinion as the providential man.

It was the first time since the Revolution that a proper name was heard in every mouth. Until then, it had been said that the National Constituent Assembly had done such and such a thing, that the people had done such and such a thing, that the Convention had done such and such a thing; now, all the talk was of this man who was to take the place of everyone else, and make the human race anonymous.

Madame de Staël, Considérations sur les principaux événements de la Révolution française, tome 2, 1817, p. 8.

Preparing for the coup

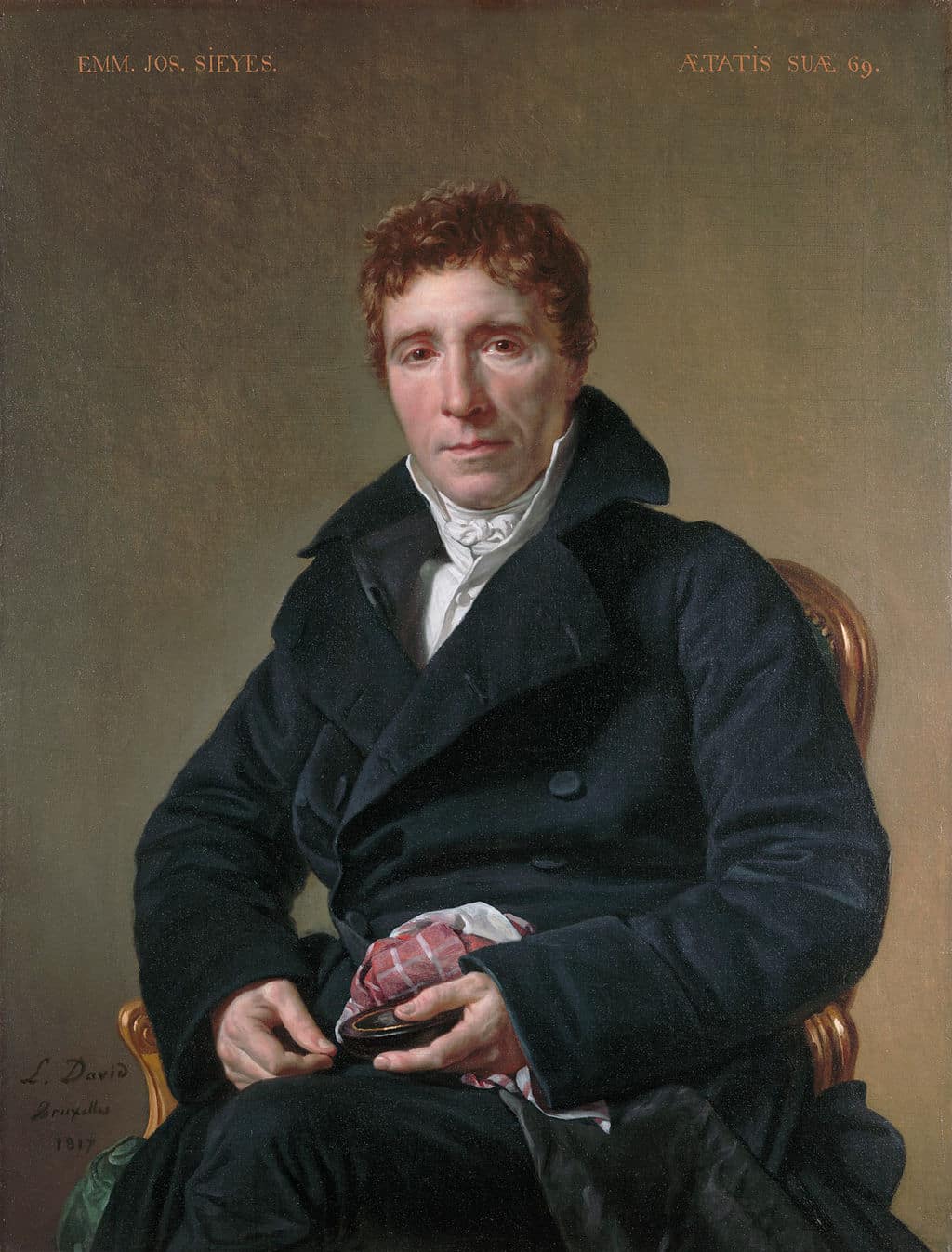

Napoleon Bonaparte may have been acclaimed, but the clamor was not unanimous. What marks this triumphant return, however, are the votes he wins across the political spectrum. From royalists to Jacobins, he found supporters who saw in him what they wanted to see, because for the General, only one thing was clear: he had to keep his political intentions vague. If he now sees power within his grasp, he is perfectly aware that the only way to bring down the Directoire is to stage a coup d’état that would be supported by public opinion. The idea was to flout the people’s representative political authority with the people’s approval, in a kind of “civilian” coup d’état. To achieve this, he had to forge the necessary alliances without revealing them, suggesting to each side that he could be their ally. But most choices are quickly discarded. His former mentor Paul Barras, Director of the Republic, was too associated with previous regimes, and the Jacobins too unpopular. That left Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748 – 1836), known as Abbé Sieyès, a strong personality whose epidermal reactions to Bonaparte’s ego were easy to foresee.

However, Sieyès and Lucien Bonaparte had drafted a constitution during the summer, which played into Bonaparte’s “civil” ambition to seize power. Although the two men stared at each other, they knew each other to be useful, and it was thus that the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire brought them to power.

18 brumaire an VII, another name for November 9, 1799

If we retain the 18th, we should also take into account the 19th of Brumaire, as this coup d’état surprisingly took its time! It took two days to overthrow the Directoire. Coup” is perhaps the least appropriate word to describe this historic event, and “trap” would undoubtedly be preferable.

The removal of the current regime was organized in two stages. Firstly, on the 18th, the representative assemblies were moved from Paris to Saint-Cloud. To justify this exceptional (and legal) measure, the organizers of the coup argued that a plot to assassinate the deputies had just been uncovered. State representatives were to be moved away from Paris, isolated, so that their protection could be better assured by the military troops led by Bonaparte. On the 19th, at Saint-Cloud, the deputies were urged to vote for the change of regime, but some refused, guessing at the real reason for the military presence. Bonaparte intervened with a speech so clumsy and awkward that even his friend and supporter Louis Antoine Bourrienne (1769 – 1834) invited him to leave the room where the furious deputies were sitting.

The stormy negotiations dragged on for two days, and it was on the evening of the 19th that Lucien Bonaparte, presiding over the Conseil des Cinq-Cents, declared the chamber legally constituted. The following day, directorial power was entrusted to three provisional consuls: Bonaparte was the first and remained so, followed by Sieyès and Roger Ducos (1747 – 1816).

The Consulate was officially installed on January 1, 1800 (11 nivôse an VIII). It was headed by the First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte, the Second Consul Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès (1753 – 1824) and the Third Consul Charles-François Lebrun (1739 – 1824). These were three different political sensibilities with the ambition of restoring national cohesion and understanding. However, this new triumvirate was not to everyone’s taste, but that didn’t matter: for the years to come, Napoleon would be the one to reckon with.

Vous aimez cet article ?

Tout comme Bonaparte, vous ne voulez pas être dérangé sans raison. Notre newsletter saura se faire discrète et vous permettra néanmoins de découvrir de nouvelles histoires et anecdotes, parfois peu connues du grand public.

Félicitations !

Vous êtes désormais inscrit à notre newsletter.

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie de Lagerac est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et l'auteure du blog « L'Art de l'Objet ».