Napoleon Bonaparte regularly demonstrated a very modern pragmatism. If our daily life owes him a lot, from the baccalaureate to garbage collection, let us recognize him for having succeeded in enforcing the numbering of buildings and houses, a challenge which exhausted the resources of many of his predecessors.

Numbering the Streets: a Long-Standing Initiative

If the numbering of streets as we know it today is quite recent, the idea is nevertheless old. In 1421 in Paris, the newly rebuilt Notre-Dame bridge, made of wood on stone piles, has no less than sixty houses which will savour against their will the water of the Seine during the destructive flood of 1499. On this bridge, the dwellings are numbered in Roman numerals and are the only ones to benefit from this treatment in the city. Once at the bottom of the river, these houses will be the only memory of a numerical experience that will not be repeated for several centuries. While waiting for the Age of Enlightenment, one orients himself in the cities by following approximate itineraries articulated on landmarks that are the signs of the houses or the specificities of the district. Failing to find his way quickly, the pedestrian can at least savor the poetry of picturesque mazes with names inherited from some curious legend. So it is with the rue du Chat-qui-Pêche as well as that of the Puits-de-l’Ermite or the rue Perdue.

In the eighteenth century, especially in its second half, it seems that the taste for clarity and simpler travel directions take over and house numbering becomes common in many cities. The exercise is most often used to better collect taxes or to accommodate more easily the troops of passing or occupying armies. But the foreign visitor or the lost provincial undoubtedly enjoys – even before the inhabitants – the comfort of strolling in an unknown city without fear of getting lost because the sign serving as a landmark closed without anyone being informed. Thus the numbering of dwellings appears for example in Prussia in 1737, in Madrid in 1750, in Milan in 1786 and in Paris in 1779. Vain undertaking in the French capital because it is an understatement to specify that Parisians are reluctant to face this initiative. As you number the day, the fresh paint indications disappear at night! At a time when rumors – and the facts! – are going well and recognize in the marking of houses an indisputable sign of the imminent passage of thieves, no one is comfortable with the idea of a clearly visible numbering even though it would be generalized to all homes and without distinction of neighborhoods or social rank.

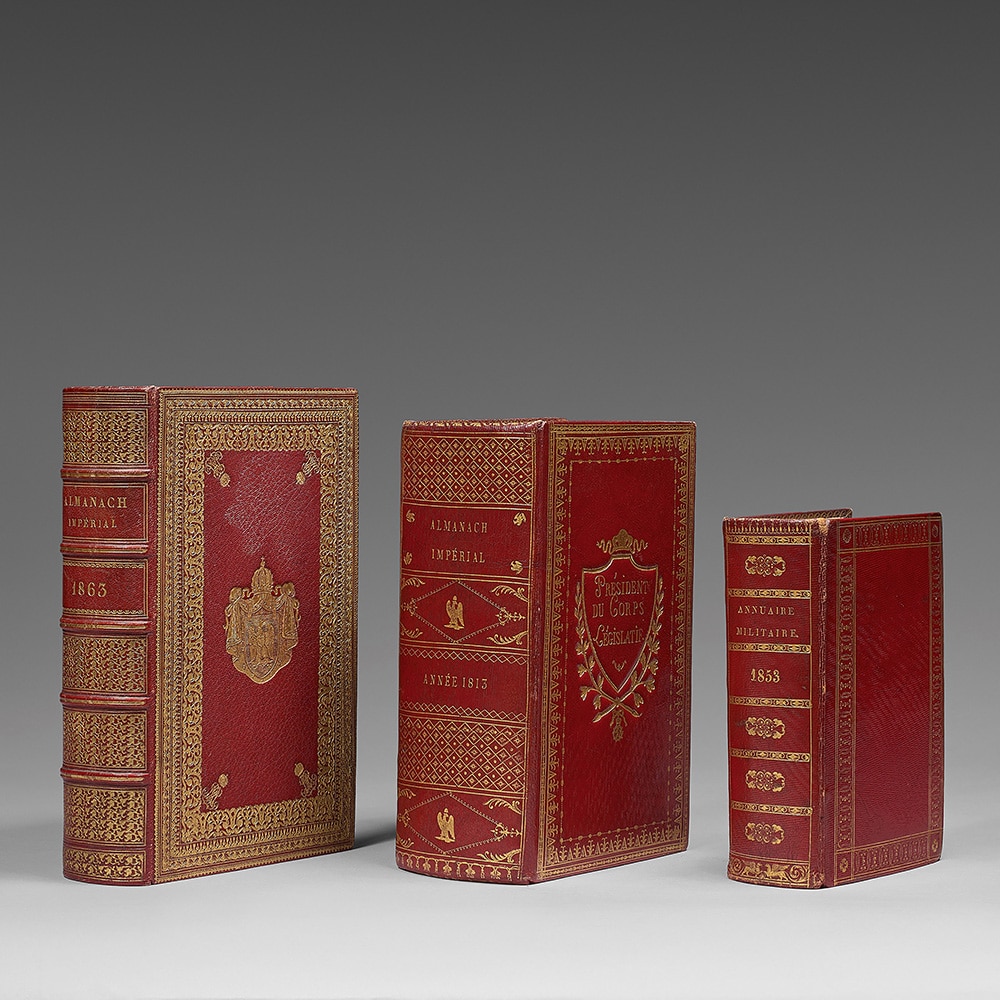

Yet the idea is gaining ground and the editors of almanacs and directories are not for nothing! It is easy to imagine the interest that such a numbering would be for them: addresses which would become precise and would need to be regularly updated so that the annual edition of almanacs and directories would turn into a particularly fruitful juicy affair. Moreover, it was on the initiative of one of these traders that the first Parisian numbering took place in 1799 and which ended in pitiful failure.

The Revolution, however, was not afraid to get to grips with the problem and concocted a system of such complexity that it was the source of particularly remarkable absurdities (numbers without continuation or the same number repeated several times in same street) and which miraculously made the system without numbering much clearer and simpler than the system being provided with numbers. All the same, Choderlos de Laclos (1741 – 1803), if he proposed a numbering system as twisted as the mind of the Vicomte de Valmont, imagined some ingenious systems such as that consisting in distributing even numbers to the streets perpendicular to the Seine and the odd numbers on the streets that ran parallel to it. If this is not quite the system set up by Napoleon I, we can recognize that he was inspired by it.

The Imperial Street Numbering System

On February 4th, 1805, a decree made street numbering compulsory. In Paris, the prefect Nicolas Frochot (1761 – 1828) is in charge of the application of this decree which is based on a system whose design was not a piece of cake!

Finally, the result makes it possible to see more clearly without creating complexities that are too crippling on a daily basis. Contrary to what Marin Kreenfelt de Storck, editor of the Almanac de Paris in 1779, advocated, the digital unit is now the house and no longer the door.

Then the numbering of the doors follows simple geographical rules capable of being applied to almost all the streets of the capital. A distinction is made between even numbers (to the pedestrian’s right) and odd numbers (to his left); the direction of the streets is oriented from upstream to downstream for streets parallel to the Seine, and from the banks to the north and south for streets oblique or perpendicular to the Seine.

Visually, the numbers are differentiated so as to facilitate understanding of the geographical position in which the pedestrian is. In the streets perpendicular or oblique to the river, the numbering is drawn in black on an ocher background while in the streets parallel to the Seine, the number is written in red, always on an ocher background.

The municipality of Paris took charge between June and September 1805 of the first numbering of the streets of the city but the maintenance of these numbers – so that they remain clearly visible – fell to the owners who one imagines that they were particularly enchanted by this new measure. Painting did not last long in the Parisian climate and the local authority published then generously a specification (height, location, color and material of the plate which could be glazed sheet, enamelled earthenware) leaving the owners the choice to invest in a numbering that did not require regular maintenance .

On June 28th, 1847, the application of the decree of the Prefect of the Seine initiated a regularization of street signs and numbering by opting for enameled porcelain plaques whose white numbers were inscribed on an azure blue background always currents in Paris and in the provinces.

When the new numbering system was applied, the problem of the Cité and Saint-Louis islands arose. Since the perpendicular streets as well as the parallel streets overlooked the Seine, it was decided to assimilate the Île de la Cité to the left bank while the Île Saint-Louis was similar to the right bank. By superstition, the number 13 of certain streets was replaced by the number 11 bis and sometimes, without any reason, streets were numbered backwards.

This decree of Napoleon I changed the way of conceiving the geographical space of a city. By facilitating all kinds of procedures, street numbering still makes it possible to move around quickly, without wasting time. Ironically, few streets named after Bonaparte allow the decree of February 1805 to be linked to its instigator. Rue Bonaparte in the 6th arrondissement of Paris evokes more the memory of the general than that of the emperor, while the quai Napoleon from 1804 is now divided into two parts, one called Quai aux Fleurs and the other Quai de la Corse, a modest evocation.

His native island and the island of Aix, the last one he trod before his rock of Sainte-Hélène, still have Napoleon streets like a few other French towns. In the absence of streets, let us remember the success of their numbering!

Marielle Brie de Lagerac

Marielle Brie de Lagerac est historienne de l’art pour le marché de l’art et l'auteure du blog « L'Art de l'Objet ».